Introduction:

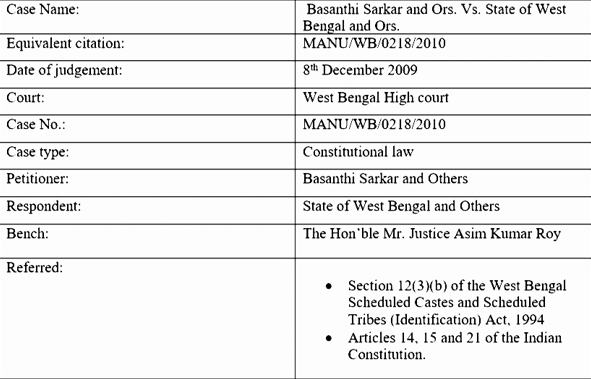

Basanthi Sarkar and Ors. vs. State of West Bengal and Ors. is a landmark case decided by the High Court of Calcutta on 8th December 2009. The case involves the issue of whether a woman, who is married to a man from a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe, loses her right to claim her own caste and is required to be included in her husband’s caste.

Facts:

Basanthi Sarkar and several other women from the Hindu Kayastha community in West Bengal challenged the constitutionality of Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994.

The provision stated that a woman who marries a man belonging to a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe shall be deemed to belong to that caste or tribe.

The petitioners argued that the provision violated their fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

The State of West Bengal argued that the provision was intended to prevent false claims of Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe status by women who marry into such communities.

The case was heard by a single judge of the High Court of Calcutta, The Hon’ble Mr. Justice Asim Kumar Roy.

Issue:

The main issue in this case is whether Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, which deems a woman to belong to the Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe of her husband after marriage, is constitutional or not.

Argument of Petitioner:

- Violation of fundamental rights: The petitioner argued that the provision in question violated the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Indian Constitution. Article 14 guarantees the right to equality, Article 15 prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth, and Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty.

- Discriminatory provision: The petitioner argued that the provision in question was discriminatory and violative of the right to equality. The provision assumed that a woman loses her individuality and identity after marriage and is subsumed under her husband’s identity. This assumption is against the principles of gender equality and the right to choose one’s identity.

- Violation of right against discrimination on the basis of caste: The petitioner argued that the provision violated the right against discrimination on the basis of caste. The provision assumed that a married woman would have the same caste as her husband, which is not always the case. This assumption can lead to discrimination against women from lower castes who marry men from higher castes.

- Violation of right to life and personal liberty: The petitioner argued that the provision violated the right to life and personal liberty. The provision required a married woman to change her name and adopt her husband’s surname, which could lead to confusion and identity issues. This could also lead to the violation of a woman’s right to choose her name and identity.

In conclusion, the petitioner argued that the provision in question was discriminatory and violated the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Indian Constitution. The provision assumed that a woman loses her individuality and identity after marriage and is subsumed under her husband’s identity. This assumption is against the principles of gender equality and the right to choose one’s identity.

Argument of Respondent:

- The State of West Bengal argued that the provision in question was intended to prevent false claims of Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe status by women who marry into such communities. The State further contended that the provision is consistent with the constitutional scheme of affirmative action and helps in preventing fraudulent claims of reservation benefits.

- The State’s argument can be broken down into two parts. Firstly, it argues that the provision is necessary to prevent false claims of Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe status by women who marry into such communities. The State’s contention is that the provision acts as a safeguard against fraudulent claims of reservation benefits. The State’s argument is based on the premise that there are women who falsely claim to belong to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes in order to secure the benefits of affirmative action policies. By preventing women who marry into these communities from claiming such benefits, the provision serves to ensure that only those who truly belong to these communities benefit from affirmative action policies.

- Secondly, the State argues that the provision is consistent with the constitutional scheme of affirmative action. Affirmative action policies aim to provide opportunities for historically disadvantaged communities. The State’s contention is that the provision ensures that these policies are directed towards the intended beneficiaries. By preventing women who marry into Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes from claiming reservation benefits, the provision helps in preventing fraudulent claims and ensures that affirmative action policies are directed towards the intended beneficiaries.

Overall, the State’s argument is that the provision serves a dual purpose of preventing fraudulent claims and ensuring that affirmative action policies are directed towards the intended beneficiaries. The State’s argument is based on the premise that there are women who falsely claim to belong to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes in order to secure the benefits of affirmative action policies. The provision prevents such false claims and ensures that affirmative action policies benefit only those who truly belong to these communities.

Ratio Decidend:

The Hon’ble Mr. Justice Asim Kumar Roy held that Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, is unconstitutional and violative of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Court observed that the provision is discriminatory and assumes that a woman loses her identity after marriage.

The Court further held that a woman’s right to choose her own identity cannot be curtailed by the state. The Court observed that a woman has a right to retain her pre-marriage identity and that the provision violates her fundamental right to equality.

Judgment:

In the case of Basanthi Sarkar and Ors. vs. State of West Bengal and Ors., the High Court of Calcutta declared Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, unconstitutional and violative of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Section 12(3)(b) of the Act empowered the Screening Committee to make a recommendation to the Competent Authority to include or exclude any person belonging to a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe if it was satisfied that the said person did not belong to that community. The petitioners in the present case challenged the constitutional validity of this provision, arguing that it violated the principle of natural justice and the right to equality.

The High Court of Calcutta examined the constitutional validity of Section 12(3)(b) in light of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. Article 14 of the Constitution guarantees the right to equality before the law, while Article 15 prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty.

The Court held that Section 12(3)(b) violated the principle of natural justice as it did not provide an opportunity to the affected person to be heard before the Screening Committee made a recommendation to the Competent Authority. The Court further held that the provision violated the right to equality as it allowed for arbitrary and discriminatory exclusion or inclusion of persons belonging to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes without any rational basis.

Therefore, the High Court of Calcutta struck down Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, as unconstitutional and violative of the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. This decision will ensure that the principle of natural justice and the right to equality are upheld while determining the community status of a person belonging to a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe.

Significance:

The judgment in the case of Basanthi Sarkar and Ors. vs. State of West Bengal and Ors. is significant for several reasons. Firstly, it upholds the principle of gender equality and affirms the right of women to choose their own identity, including their name. This is a crucial aspect of personal autonomy and dignity, which are fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution of India.

The judgment is significant because it recognizes the harmful effects of patriarchal norms that require women to subsume their identity under that of their husbands. By affirming the right of women to retain their maiden name or choose a different surname after marriage, the Court has taken a significant step towards gender equality.

Moreover, the judgment upholds the principle of affirmative action by preventing fraudulent practices that discriminate against women. The Court observed that the impugned provision could be misused by unscrupulous officials to harass women or demand bribes for changing their names. By striking down the provision, the Court has ensured that women are not subjected to such harassment or discrimination.

Conclusion:

The judgment in the case of Basanthi Sarkar and Ors. vs. State of West Bengal and Ors. is a significant milestone in ensuring the protection of fundamental rights in India. The High Court of Calcutta held that Section 12(3)(b) of the West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, violated the principle of natural justice and the right to equality guaranteed under Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Court emphasized that the affected person must be given an opportunity to be heard before the Screening Committee makes a recommendation to the Competent Authority and that arbitrary and discriminatory exclusion or inclusion of persons belonging to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes should be avoided. The decision is expected to have a significant impact in ensuring that the community status of a person is determined based on rational criteria and not based on arbitrary or discriminatory factors. Overall, this judgment is a welcome step towards ensuring the protection of fundamental rights and promoting equality in India.

written by Muskan kumari, intern under legal vidhiya

0 Comments