This Article is Written by Ayni Saad of second year of Faculty of Law, University of Delhi, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

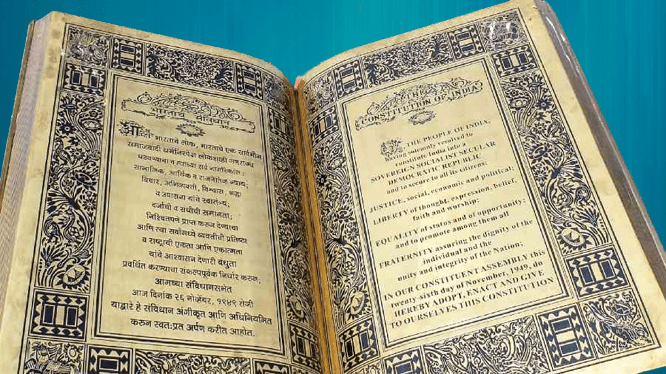

Constitutional amendments are changes made to the fundamental law of a country or state, typically involving alterations to the text of a constitution. In India, the Constitution provides for a specific process for amending its provisions, set out in Article 368.[1]

The Indian Constitution has been amended over 100 times since its adoption in 1950. Amendments can be initiated by either house of Parliament and must be passed with a special majority, which requires the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting, as well as a majority of the total membership of each house.

Certain types of amendments require ratification by the state legislatures in addition to the special majority in both houses of Parliament. These include changes to the federal nature of the Constitution, such as amendments affecting the distribution of powers between the Centre and the states.

The process of amending the Constitution in India is a complex and often contentious one, as amendments can have far-reaching implications for the functioning of government and the protection of citizens’ rights. The Supreme Court of India has played a significant role in interpreting the Constitution and reviewing the constitutionality of amendments, particularly with respect to the doctrine of the basic structure, which holds that certain fundamental features of the Constitution cannot be altered by amendment.

Overall, constitutional amendments are an important tool for ensuring that a country’s fundamental law remains relevant and responsive to changing times, while also preserving the basic principles and values that underpin its political system.

Keywords: Amendment procedure, Parliament, Constitution, Fundamental Rights, Citizens, Judicial Review, Basic Structure, Ratification, Limitations, Assent.

INTRODUCTION TO THE PROCEDURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS (Art.386)

In India, the process of amending the Constitution is governed by Article 368 of the Constitution.[2] According to this article, an amendment to the Constitution can be initiated by either House of Parliament or by the President of India. In addition, the process of Amending the Constitution is borrowed by the constitution of South Africa.

The process of amending the Constitution requires a special majority. This means that the amendment must be passed by a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting in each House of Parliament. Additionally, the amendment must be ratified by at least half of the state legislatures in the country.

Once the amendment has been passed by both Houses of Parliament and ratified by the required number of state legislatures, it must be assented to by the President of India. However, certain provisions of the Constitution cannot be amended. These provisions include the fundamental rights of citizens, the basic structure of the Constitution, and the provisions related to the representation of states in the Parliament.

Overall, the amending process in India is designed to be a rigorous and difficult process, meant to ensure that any changes made to the Constitution reflect the will of the people and the needs of the country as a whole.

PROCEDURE FOR AMENDING THE CONSTITUITION OF INDIA

ARTICLE 368: Article 368 of the Constitution of India deals with the procedure for amending the Constitution. It outlines the various steps and requirements that must be met in order to make changes to the Constitution.

1) POWER TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION [ART.368(1)]

In India, the power to amend the Constitution is vested with the Parliament. This power is set out in Article 368 of the Constitution. The Parliament can amend any provision of the Constitution, including fundamental rights, subject to certain limitations.[3]

However, the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution is not absolute. The Constitution itself provides certain limitations on this power to ensure that the basic structure of the Constitution is not altered in a manner that would undermine its fundamental principles.

The doctrine of the basic structure, developed by the Supreme Court of India, holds that certain fundamental features of the Constitution cannot be altered by amendment. These features include the supremacy of the Constitution, the sovereignty of India, the democratic form of government, the federal character of the Constitution, and the protection of fundamental rights.

Additionally, certain types of amendments require ratification by the state legislatures in addition to the special majority in both houses of Parliament. These include changes to the federal nature of the Constitution, such as amendments affecting the distribution of powers between the Centre and the states.

Overall, while Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, this power is subject to certain limitations to ensure that the basic structure of the Constitution is preserved and that the Constitution remains true to its fundamental principles.

2) AMENDMENT BY SPECIAL MAJORITY [ART. 368(2)]

Special majority is a term used in the Indian Constitution to refer to the number of votes required in the Parliament or the state legislatures to pass certain types of laws or amendments.[4]

In the case of constitutional amendments, a special majority is required to pass them. Article 368 of the Constitution sets out the procedure for amending the Constitution, and it requires a special majority in both houses of Parliament:

- A two-thirds majority of the members present and voting in each house of Parliament; and

- A majority of the total membership of each house of Parliament.

This means that the amendment must be supported by at least two-thirds of the members present and voting in each house of Parliament, and by a majority of the total membership of each house.

In addition to the special majority, certain amendments also require ratification by a majority of the state legislatures. These include amendments that affect the federal nature of the Constitution, such as changes to the distribution of powers between the Centre and the states.

The requirement of a special majority for constitutional amendments is intended to ensure that any changes to the Constitution are made only after careful consideration and broad consensus. It also reflects the idea that the Constitution is a fundamental and enduring document that should not be subject to frequent or casual changes.[5]

3) RATIFICATION BY THE STATE LEGISLATURE

In India, certain types of constitutional amendments require ratification by the state legislatures in addition to the special majority in both houses of Parliament. These include amendments that affect the federal nature of the Constitution, such as changes to the distribution of powers between the Centre and the states.

Under Article 368 of the Constitution, if a proposed constitutional amendment falls within the purview of this category, it must be ratified by the legislative assemblies of at least half of the states before it can be presented to the President for his or her assent.[6]

The process of ratification is as follows:

- The proposed amendment is presented to the President for his or her assent after it has been passed by both houses of Parliament with a special majority.

- The President refers the amendment to the state legislatures for ratification.

- The amendment must be ratified by the legislative assemblies of at least half of the states within a period of six months from the date of its presentation to the President.

- Once the required number of states have ratified the amendment, it can be presented to the President for his or her assent.

It is worth noting that while the process of ratification by the state legislatures is required for certain types of constitutional amendments, it does not necessarily guarantee their ultimate success. The judiciary retains the power of judicial review to strike down any amendment that is found to be unconstitutional or that violates the basic structure of the Constitution.

4) PRESIDENT’S ASSENT TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT BILL

In India, after a constitutional amendment is passed by both houses of Parliament with a special majority, it is sent to the President of India for his or her assent.

Under Article 111 of the Constitution, the President has three options when presented with a bill for his or her assent:

- Give assent to the bill;

- Withhold assent to the bill; or

- Return the bill for reconsideration to the Parliament, either with a message recommending certain changes or amendments, or without any such message.[7]

If the President gives assent to the bill, it becomes law and the Constitution is amended accordingly. If the President withholds assent to the bill, it is deemed to have been rejected and cannot become law. If the President returns the bill for reconsideration, the Parliament may make any changes or amendments it deems fit, and the bill must again be passed by both houses of Parliament with a special majority before it is sent back to the President for his or her assent.

The President’s role in the process of constitutional amendment is largely ceremonial and he or she is expected to act on the advice of the Council of Ministers. However, the President does have the power to ask for clarification or reconsideration of the bill, which can sometimes lead to delays or changes in the amendment process.

5) THE DOCTRINE OF BASIC STRUCTURE [ART. 368(3)]

The concept of basic structure is an important principle in the Indian Constitution, which has been established through a series of landmark judgments by the Supreme Court of India.[8] The basic structure doctrine holds that there are certain fundamental features or principles of the Constitution that cannot be amended by the Parliament under its amending power, as enshrined in Article 368.

The concept of basic structure originated from the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), in which the Supreme Court held that the Parliament’s amending power under Article 368 is not an absolute power and that certain basic features or elements of the Constitution are immune from amendment. The Court held that any amendment that destroys or abrogates the basic structure of the Constitution is void and unconstitutional.[9]

The exact content and scope of the basic structure doctrine have been a matter of debate and interpretation over the years. However, some of the features that have been identified as part of the basic structure of the Constitution include:

- Supremacy of the Constitution

- Sovereignty, democratic and republican character of the Indian polity

- Separation of powers between the executive, legislative and judiciary

- Federal character of the Constitution

- Rule of law and protection of fundamental rights

- Independence of the judiciary

- Free and fair elections

- Limited power of Parliament to amend the Constitution

The concept of basic structure is significant in protecting the core values and principles of the Indian Constitution and ensuring that they remain unaltered, regardless of the political dispensation in power.

JUDICAL REVIEW

Judicial review in the context of constitutional amendments refers to the power of the judiciary to examine and strike down constitutional amendments that are inconsistent with the basic structure of the Constitution or violate the fundamental rights of citizens.

In India, the Supreme Court has held that while the Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution under Article 368, this power is not absolute and is subject to the basic structure doctrine. The basic structure doctrine, as laid down in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case, holds that the Parliament cannot amend the Constitution in a way that alters its basic structure or destroys its essential features.

The Supreme Court has also held that the power of judicial review is an essential feature of the Constitution and cannot be taken away by a constitutional amendment. This means that the judiciary has the power to examine and strike down constitutional amendments that violate the fundamental rights of citizens or undermine the basic structure of the Constitution.

However, the scope of judicial review in the context of constitutional amendments has been a matter of debate and controversy. Some argue that the judiciary should exercise restraint and not interfere with the will of the elected representatives of the people, while others believe that the judiciary has a duty to protect the Constitution and the rights of citizens from any infringement by the state.

In practice, the judiciary has used its power of judicial review to strike down several constitutional amendments that were seen as violating the basic structure of the Constitution or the fundamental rights of citizens. These include the 24th Amendment, which sought to restrict the scope of judicial review of constitutional amendments, and the 99th Amendment, which introduced a new mechanism for the appointment of judges to the higher judiciary.

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENMENDMENTS AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS [PART 3]

Fundamental rights are enshrined in Part III of the Indian Constitution, and they protect the basic rights and freedoms of citizens against any arbitrary action by the State.[10] However, the amending procedure under Article 368 imposes certain limitations on the power of the Parliament to amend the fundamental rights provisions. Here are some key points regarding the relationship between fundamental rights and the amending procedure:

- Fundamental rights can be amended: Although fundamental rights are considered sacrosanct, they are not absolute and can be amended under certain circumstances. However, the procedure for amending the fundamental rights provisions is more stringent than that for amending other provisions of the Constitution.

- Amendment procedure for fundamental rights: An amendment to any of the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution can only be made by the Parliament by a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting in each House, and it must also be ratified by at least half of the state legislatures in India.

- Limitations on amending fundamental rights: The Parliament cannot amend the fundamental rights provisions in such a way that they take away or abrogate the basic essence of the right. The Supreme Court has also held that any amendment to the fundamental rights provisions that destroys or takes away their basic structure or identity would be unconstitutional.

- Judicial review: The Supreme Court of India has the power to review the constitutional validity of any amendment made to the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.

Overall, the amending procedure for fundamental rights is more rigorous and complex than that for other provisions of the Constitution. This is to ensure that any amendments made to the fundamental rights provisions do not undermine the core values and principles of the Constitution, including the protection of citizens’ basic rights and freedoms.

RELEVANT JUDICIAL PRECEDENTS

ARTICLE 13: Article 13 of the Constitution of India is a fundamental rights provision that lays down the doctrine of “law declared void for inconsistency with fundamental rights.”[11] The article provides that any law made by the state that violates or is inconsistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution shall be void.

Article 13 applies to all laws made by the state, including pre-constitutional laws, laws made by the Parliament, and laws made by the state legislatures. The article also includes within its ambit any executive action that violates or is inconsistent with the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.

The term “law” under Article 13 includes not only statutory laws but also constitutional amendments, rules, regulations, ordinances, by-laws, and notifications. The article further specifies that any law that is declared void under this provision shall be void to the extent of its inconsistency with the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.

The purpose of Article 13 is to safeguard the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution and ensure that they are not abrogated or abridged by the state. It empowers the judiciary to strike down any law that violates the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution, and thus, plays a crucial role in protecting the rights of citizens in India.

SANKARI PRASAD SINGH DEO V. UNION OF INDIA, 1951

An important case in Indian constitutional law is Sankari Prasad Singh Deo v. Union of India. In 1951, a Constitution Bench of the Indian Supreme Court heard it. The case concerned the issue of whether the Indian Parliament’s ability to change the Constitution in accordance with Article 368 was unrestricted or subject to judicial scrutiny.[12]

In a 5-4 judgement, the Supreme Court affirmed the First Amendment’s legality and ruled that the Parliament had unrestricted ability to modify the Constitution. The Indian Parliament’s ability to change the Constitution under Article 368, according to the Court, is a sovereign power and is not constrained by any rights, including basic freedoms.

The Court additionally declared that the Constitution did not grant the judiciary the authority to evaluate any modifications made to the Constitution by the Parliament. The Court reasoned that the notion of separation of powers would be broken if the Parliament’s amending authority were susceptible to judicial scrutiny.

The theory of the Indian Parliament’s “unlimited power of amendment” under Article 368 of the Constitution was established by this decision. However, in the historic case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala in 1973, the Supreme Court overturned this judgement and concluded that the amending authority of the Parliament was susceptible to judicial review and was constrained by the fundamental design of the Constitution.

GOLAKNATH V. STATE OF PUNJAB, 1967

The Golak Nath case is a landmark judgment delivered by the Supreme Court of India on 27 February 1967. The case was brought before the court as a result of a constitutional challenge to the 17th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1964, which sought to restrict the scope of fundamental rights and empower the Parliament to amend any part of the Constitution, including the fundamental rights provisions, by a simple majority.[13]

The Supreme Court, in its judgment, held that the Parliament did not have the power to amend the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution, as they constituted the basic structure of the Constitution. The court ruled that the Parliament could not change the basic features of the Constitution under the guise of amending it.[14]

The judgment in the Golak Nath case was a significant development in the evolution of the Indian Constitution, as it marked a departure from the earlier trend of upholding parliamentary supremacy and gave a greater role to the judiciary in interpreting the Constitution. The ruling was also seen as a victory for federalism and individual rights, as it prevented the central government from encroaching on the powers of the states and protected the rights of citizens from arbitrary interference by the state.

However, the judgment also sparked a debate on the role of the judiciary in interpreting the Constitution and the limits of judicial review. The Parliament, in response to the judgment, passed the 24th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1971, which sought to restrict the scope of judicial review by amending Article 13 and introducing a new provision, Article 368(4), to prevent the courts from declaring any constitutional amendment invalid on the grounds that it violated the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.[15][16]

24TH CONSTITUTIONAL (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1971

The 24th Constitutional Amendment was passed by the Indian Parliament in 1971 in response to the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in the Golak Nath case.[17] The amendment sought to restrict the scope of judicial review of constitutional amendments and protect the Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution from judicial scrutiny.

The 24th Amendment Act inserted a new provision, Article 13(4), into the Constitution, which excluded constitutional amendments from the definition of “law” under Article 13. Article 13 provides that any law that is inconsistent with the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution shall be void. By excluding constitutional amendments from the definition of “law,” the Parliament sought to prevent the courts from striking down any constitutional amendment as unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the fundamental rights provisions of the Constitution.

In addition, the 24th Amendment Act added a new clause, Clause (4), to Article 368 of the Constitution, which conferred plenary power on the Parliament to amend any part of the Constitution, including the fundamental rights provisions, by a simple majority. The amendment, however, provided that no amendment made under Clause (4) could be challenged in any court of law on any ground.

The 24th Amendment Act was controversial, as it was seen by some as an attempt by the Parliament to circumvent the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Golak Nath case and consolidate its power over the Constitution. The amendment was challenged before the Supreme Court in the Kesavananda Bharati case in 1973, which ultimately led to the development of the “basic structure doctrine” in Indian constitutional law.

KESHAVANANDA BHARATI CASE V. STATE OF KERALA, 1973

Keshavananda Bharti v. State of Kerala, also known as the Fundamental Rights case, is a landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of India, delivered on April 24, 1973. The case is widely regarded as one of the most important judgments in the history of Indian constitutional law as it established the doctrine of basic structure.

The case was brought before the court by Swami Keshavananda Bharti, the head of the Edneer Mutt in Kasargod district of Kerala, who challenged the constitutionality of the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. The case was heard by a bench of thirteen judges and the arguments were spread over 68 days, making it the longest hearing in the history of the Supreme Court.

In its judgment, the court upheld the constitutionality of the Kerala Land Reforms Act, but at the same time, it also held that there are certain basic features of the Constitution that cannot be abrogated or abridged by Parliament through its amending power. The court held that the power to amend the Constitution under Article 368 is not unlimited and that the basic structure of the Constitution cannot be altered.

The court did not explicitly define the basic structure of the Constitution, but it did list some of its essential features such as the supremacy of the Constitution, the rule of law, the independence of the judiciary, the federal character of the Constitution, the secular character of the Constitution, and the democratic character of the Constitution.[18]

The Keshavananda Bharti case has had a profound impact on Indian constitutional law and has been cited in numerous subsequent judgments. It has also been used to strike down various constitutional amendments that were deemed to be violative of the basic structure of the Constitution.

42ND CONSTITUTIONAL (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1976

The 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976 made significant changes to the Constitution of India, including limiting the scope of judicial review. The amendment is also known as the “Mini Constitution” as it made significant changes to the Constitution of India.

Prior to the amendment, the judiciary had wide powers to review constitutional amendments made by Parliament. However, the 42nd Amendment Act added a new clause (4) to Article 368 of the Constitution, which declared that “no amendment of this Constitution… shall be called in question in any court on any ground.”[19]

This meant that the judiciary’s power to review constitutional amendments was significantly curtailed, and Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was increased. The amendment was seen as an attempt by the government to limit the independence of the judiciary and to reduce the effectiveness of judicial review.

However, in the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, the Supreme Court held that even though Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, this power is not absolute. The court held that there are certain basic features of the Constitution that cannot be amended, including the basic structure of the Constitution.

The court also held that the power of judicial review is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution and cannot be taken away by Parliament through its amending power. Thus, while the 42nd Amendment Act curtailed the scope of judicial review, subsequent judgments of the Supreme Court have reaffirmed the importance of judicial review as a key feature of the Constitution that cannot be abridged.

MINERVA MILLS V. UNION OF INDIA, 1980

One of the most significant cases in Indian constitutional law is Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India. In 1980, a Constitution Bench of India’s Supreme Court heard it. The lawsuit concerned the constitutionality of the 42nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution, which the Indian Parliament ratified in 1976.[20]

In a 4-1 judgement, the Supreme Court invalidated a number of the 42nd Amendment’s clauses, notably Article 31C. The Court ruled that the Constitution’s fundamental design placed restrictions on the modifying authority granted to the Parliament under Article 368 and made it susceptible to judicial scrutiny. The Supreme Court ruled that several fundamental elements of the Constitution, including the separation of powers, federalism, and the rule of law, could not be changed.

The Court also determined that by giving the Directive Principles of State Policy precedence over the fundamental rights protected by the Constitution, Article 31C violated the Constitution’s core principles. The Court said that any amendment that disrupted the Constitution’s goal of balancing the opposing interests of the state and the person would be invalid.

This decision established the fundamental idea that judicial review might limit the Parliament’s modifying power. The fundamental structure of the Constitution theory, which was originally stated in the seminal case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, was upheld by the Minerva Mills v. Union of India ruling.

NO JOINT SESSION IN RESPECT TO CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT BILLS

While the Constitution provides for a detailed procedure for the amendment of the Constitution, it does not specifically provide for a joint session under Article 108(1) of both houses of Parliament to be held in case of disagreement between the two houses on a constitutional amendment bill.[21]

Article 368(2) of the Constitution provides that a constitutional amendment bill can be introduced in either house of Parliament, and it must be passed by each house separately with a two-thirds majority of members present and voting.[22] However, if the two houses of Parliament disagree on a constitutional amendment bill, there is no provision for a joint session to be held.[23]

The lack of provision for a joint session in the case of a disagreement between the two houses of Parliament on a constitutional amendment bill was noted by the Supreme Court in the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala. The court held that the absence of a provision for a joint session in such cases does not mean that the President can never summon a joint session of Parliament for the purpose of passing a constitutional amendment bill.

However, the court also held that a joint session should be summoned by the President only in exceptional circumstances, and after considering all relevant factors, including the nature and importance of the amendment, the views of the two houses of Parliament, and the constitutional implications of the amendment. The court also held that a constitutional amendment passed by a joint session of Parliament would be subject to judicial review on the same grounds as any other constitutional amendment.

CONCLUSION

So far, the decision in Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala has been followed in subsequent cases by the Supreme Court. Any part of the constitution can be amended after complying with the provisions laid down in Art. 368. However, no provision of the Constitution or any part thereof can be amended if it takes away or destroys any of the “Basic Features” of the Constitution.

It is clear from the above that the amending process prescribed by our Constitution has certain distinctive features as compared with the corresponding provisions in the leading Constitution of the word. The procedure of amendment must be classed as “rigid” insofar as it requires a special majority and in some cases a special procedure for amendment as compared with the procedure prescribed for ordinary legislation.

RFERENCES

Art. 368(1), (2), (3) & (4), The Constitution of India.

Art. 13, (4), The Constitution of India.

Art. 111, The Constitution of India.

Art. 108(1), The Constitution of India.

The Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971.

The Constitutional (42nd Amendment) Act, 1976

Durga Das Basu, Introduction to the Constitution of IndiaI, 193 (26th ed., 2022)

Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Keral, (1973) 4 SCC 225.

Golak Nath v. State of Kerala, 1967 AIR 1643, 1967 SCR (2) 762.

[1] Art. 368, The Constotution India.

[2] Art. 368, The Constitution of India.

[3] Art. 368(1), The Constitution of India.

[4] Art. 368(2), The Constitution of India.

[5] Durga Das Basu, Introduction to The Constitution of India, 192 (26th ed.,2022)

[6] Art. 368(2), The Constitution of India.

[7] Art. 111, The Constitution of India.

[8] Art. 368(3), The Constitution of India.

[9] Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Keral, (1973) 4 SCC 225.

[10] Part III, The Constitution od India.

[11] Art. 13, The Constitution of India.

[12] Sankari Prasad Singh v. Union of India, (1951) SCC 458.

[13] The Constitution (17thAmendment) Act, 1964.

[14] Golak Nath v. State of Kerala, 1967 AIR 1643, 1967 SCR (2) 762.

[15] The Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971.

[16] Art. 368(4), The Constitution of India.

[17] The Constitution (24th Amendment) Act, 1971.

[18] Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Keral, (1973) 4 SCC 225.

[19] The Constitution (42nd Amendment) Act, 1976

[20] Minerva Mills v. Union of India, (1980) SCC 1789.

[21] Art. 108(1), The Constitution of India.

[22] Art. 368(2), The Constitution of India.

[23] Durga Das Basu, Introduction to the Constitution of IndiaI, 193 (26th ed., 2022)

0 Comments