Introduction

Law is a set of obligations and principles imposed by the government for securing welfare and providing justice to society. India’s legal framework reflects the social, political, economic, and cultural components of society. The common law system garnered its roots throughout the history of the legal system in India. The main sources of law in India are the Constitution, statutes, customary law and the judicial decisions of superior courts. The laws passed by parliament may apply throughout all or a portion of India, whereas the laws passed by state legislatures normally apply within the borders of the states concerned.

History of Indian legal system

- Judicial system during the Ancient Hindu Period

The Vedic, Bronze, and Indus Valley civilizations all contributed to the legal judiciary system in India. The first known source of law in India was classical Hindu law. “Dharma” deals with legal and religious duties.

The main sources of Hindu Law or “Dharma” are Veda, Smriti, and Aâchâra.

Vedas consisted of hymns, praises, customs, and religious obligations. The four Vedas:

- Rigveda,

- Yajurveda,

- Samaveda, and

- Atharvaveda

Smritis defined obligations, practices, and teachings of religion that an individual needs to practice in society. ‘Dharmashastra’ is a Smriti and one of the primaeval legal texts written in Sanskrit, containing information such as the principles of law, duties of the king, manner of

- evidence, and witnesses. The king was in command and was counselled by his ministers. The legal procedure was Vyavahāra under Hindu law.

The stages of legal procedure were:

the plaint, the reply, the trial, and the decision.

Manusmriti (200 BC – 200 CE), Yajnavalkya Smriti (200 – 500 CE), Naradasmriti (100 BC – 400 CE), Vishnu Smriti (700 – 1000 CE), Brhaspatismriti ( 200 – 400 CE) and Katyayanasmriti (300 – 600 CE) are some of the prominent Smritis from Dharmashastra texts that were used as precedents.

- “Manusmriti” is the ancient set of rules that binds a person by specific responsibilities and obligations. The framework of the judicial system was constructed throughout the era of dynasties to solve various civil and criminal issues.

‘Achâra’ was the customary norm of a particular society. Achâra was used in matters where Vedas and Smritis were silent.

THE ANCIENT: THE CONCEPT OF `DHARMA`

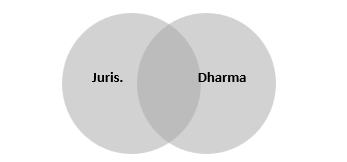

Indian jurisprudence is rich in essence because of the various sources of law it emerges from. It gets validity and recognition from various religious laws, local customs, and traditions. Dharma forms the main foundation of Indian jurisprudence. Due to its importance in Hindu traditions, Dharma played a big role in shaping Indian law.

Meaning of Dharma:

Dharma is a crucial idea with different implications in Indian religions. Dharma is the main source of Indian Jurisprudence. It has a big role in forming various Indian Laws.

Dharma is ‘Duty’

Among the Hindus the word ‘Dharma’ is used for giving justice in ancient times and according to them Dharma includes a person’s moral and social obligations as an individual as well as a member of the society.

According to

- Buddhists = Dharma is a cosmic law

- Jains and Sikhs = Dharma is religious paths.

The main motive of Dharma is to conduct human behavior in its cosmic and human context.

Sources of Dharma

According to Hinduism, salvation or Moksha is the eternal Dharma for human beings. Dharma has been derived from the Vedic concepts of ,

- Veda, Upanishads and Shrutis: In Vedic texts like Rig Veda, Dharma has been defined “to mean the foundation of the universe. “Later on, Hindu texts like the Upanishads defined Dharma in a more moralistic way. In a nutshell, Shrutis or Vedas depict the life of our early ancestors, a thin way of life, way of thinking, customs, thought, but does not deal with rules of law in a systematic manner. The existing rules of law have been deducted from the vast source of the four Vedas.

- With the changing pattern of society, after the Vedic Period, the need to understand the Veda in a new light arose. The Hindu legal codes like Manusmriti used Dharma to mean both religious and legal duties of men in their various relations. Most of the Dharmasutras mingled religious and moral perspectives with secular law.

- The Smritikars in this part have dealt with the law under 18 titles and 132 subtitles. Many rules and principles propounded by the Smritikars at that time have found a place even in modern laws.

- Dharmashastras: The Hindu legal system is one the most ancient systems and it is wholly dependent on the idea of Dharma. It can be found as Dharmashastras among the Hindus. Most of the Dharmashastras is divided into three parts:

- Achara, = rules of religious observance

- Vyavahara, = Civil law

- Prayaschitta.= penance and expiation (penalties, amendments)

The Smritikars in this part have dealt with the law under 18 titles and 132 subtitles. Many rules and principles propounded by the Smritikars at that time have found a place even in modern laws.

Some important Smritis are

- Manusmriti: Manusmriti, also known as Manava-dharmashastra is a code of laws given by Manu. It focuses on cosmogony, the sacraments (Samskaras), study of Vedas, initiation (upanayana), marriage, hospitality, the conduct of women and wives, means of purification, and the laws of the Kings. Manusmriti does not create any distinction between religious law and practices, and it can be said that it is some sort of secular law created in the ancient period.

- Naradasmriti is a kind of Dharmashastra that is juridical in nature. It does not deal with righteous conduct and penances. In fact, it covers the area of legal procedure of the original text of Manu. Naradasmriti is also known as the ‘juridical text par excellence’ as it is focused only on procedural and substantive law.

- Yajnavalkya Smriti deals with rules of procedural law

Some other Smritis are Katyayana Smriti, Prasara, and Brihaspati Smriti.

- Arthashastra was written by the Great Mauryan Empire Kautilya which deals with the qualities and disciplines needed for a king to rule his subjects more expeditiously as it refers to the pursuit of worldly goods, personal success, stability, and social status. It is one of the most important treatises in the Indian Vedic Civilization which led ancient India to a more well-organized society.

- Ramayana and Mahabharata: Later, Hindu Epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata has also defined Dharma as the aim of an individual is to perform all his responsibilities towards others. These Epics often represent authentic figures as ‘Dharmaraja’. The scope of Dharma has expanded from time to time with the changes of the society and this interpretation of Dharma is being continued till now

Nature of Dharma

In the Vedic era in Rig Veda Dharma was meant as the foundation of the universe which means that God created life by using the principles of Dharma. The Hindu Jurisprudence has always given more importance to an individual’s duty rather than rights.

On the other hand, Hindu Legal code like Manusmriti gives it a legalistic meaning and specifically delas with religion, administration, economics, social justice, civil and criminal laws, marriage and succession etc., Apart from all these factors, divinity is the main source of all social, legal, political and spiritual rights. Thus, we can say that Dharma is a multi-layered concept.

Relation Between Jurisprudence and Dharma

For attaining social justice as well as justice under law, government should make laws which people are willing to accept. In ancient times, Dharma was recognized as law in the society and people accepted to follow those Shastras and Smritis. Dharma leads to the foundation of multiple affairs of the society; thus, we can say it constitutes rules for working of the society.

The rule of law as mentioned in the Dharmashastras and Dharmasutras is the very most important base of Indian Jurisprudence and as society evolves, the rule of law should also evolve along with it.

- Law and judicial system during the Mughal Empire

During the reign of the Mughal Empire, Mahakuma-e Adalat was found to provide justice to the people. Quran, Sunna and Hadis, Ijma, and Qiyas were the primary sources of Muslim law. The principles governing the judicial procedure:

The hierarchy of the judicial system was classified into:

- At capital level

The Emperor’s Court was the capital’s highest court, presided by the emperor. It had subordinate courts,

- The Chief Court dealt with the original, appellate civil and criminal cases

The two types of Chief Court.

- The Delhi Court of Qazi: regulated the local civil & criminal cases

- The Qazi-e-Askar Court: regulated military cases of the capital.

- Chief Revenue Court dealt with the cases related to revenue matters

2. At state level

The Governor’s Court and Bench or Adalat-e-Nazim the cases at the state level are classified into

- Chief Appellate Court: in charge of the state’s civil and criminal matters

- Chief Revenue Court: in charge of the state’s revenue issues.

3.At district level

The district-level was managed and supervised by Chief Civil and Criminal Court. It was classified into

- District Qazi Court for regulating civil and criminal cases,

- Faujdari Adalat for handling state security,

- Kotwali, for regulating petty criminal cases and

- Amalguzari Kachari for regulating revenue cases.

4.At Parganas level

At the Parganas level, a group of villages or the surrounding areas were governed by

- Adalat-e-Pargana which were headed by Qazi-e-Pargana regulating civil and criminal cases,

- Kotwali regulated petty criminal cases and

- Amin-e-Parganah dealt with revenue matters.

5. At village level

At the village level, the panchayat handled civil and criminal cases. The president of the village panchayat was the sarpanch and the rest of the members were elected by the villagers.

- Indian legal system during the British reign

The East India Company established the judicial system in India during the British era by creating Mayor’s Courts in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta formulated under the Charter of 1726 and governed under the common law. During the Mayor’s Court’s regulation, certain constraints were discovered. It lacked details on the kind of law it would regulate and since the English law was the main source of law, in certain instances, it neglected personal and customary laws. By the Charter of 1753, mayor courts were re-established and brought under the regulating authority of the Governor and the Council. The Council of Privy was the highest court of appeal.

The judicial system was separated into

- District Diwani Adalats for civil cases and

- District Fauzdari Adalats for criminal matters and

The Supreme Court at Calcutta was established under the Regulating Act of 1773 AD under Warren Hastings’ administration (1772-1785 AD). The District Faujdari Court was abolished during the reign of Cornwallis (1786-1793 AD), and the Circuit Court and Mal Adalats were established. Sadar Nizamat Adalat was relocated to Calcutta and placed under the administration of the Governor-General and members of the Supreme Council, assisted by Chief Qazi and Chief Mufti. A district judge presided over the

District Diwani Adalat, which was renamed District, City, or Zila Court. He also established civil courts for both Hindus and Muslims, such as the Munsiff Court, the Registrar Court, the District Court, the Sadar Diwani Adalat, and the King-in-Council.

Several commissions of the law were published under the reign of William Bentinck (1828-1835 AD) in the form of

- the Civil Procedure Code of 1859,

- the Indian penal Code of 1860, and

- the Criminal Procedure Code of 1861, and various guidelines addressing particular matters and circuit courts were abolished.

- Introduction to the Government of India Act, 1935

Government of India Act, 1935 was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It defined the characteristics of the government from “unitary” to “federal”. Powers were dispersed between centre and state to avoid any disputes.

In 1937, Federal Court was established and had the jurisdiction of appellate, original and advisory. The powers of Appellate Jurisdiction extended to civil and criminal cases whereas the Advisory Jurisdiction was extended with the powers to Federal Court to advise Governor-General in matters of public opinion. The Federal Court operated For 12 years and heard roughly 151 cases. The Federal Court was supplanted by India’s current Apex Court, the Supreme Court of India.

Types of laws in the Indian legal system

The Constitution of India, 1950 is the foremost law that deals with the framework of the codes, procedures, fundamental rights and duties of citizens and powers, and duties of government. The laws in India are interconnected with each other forming a hybrid legal system.

The classification of laws in the Indian judiciary system:

- Criminal Law

Criminal law is concerned with laws pertaining to violations of the rule of law or public wrongs. Criminal law is governed under the Indian Penal Code, 1860, and the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973. The Indian Penal Code, 1860, defines the crime, its nature, and punishments whereas the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, defines exhaustive procedure and punishments of the crimes.

Murder, rape, theft, and assault are all examples of criminal offences under the law.

- Civil Law

Matters of disputes between individuals or organisations are dealt with under Civil Law. Civil courts enforce the violation of certain rights and obligations through the institution of a civil suit. Civil law primarily focuses on dispute resolution rather than punishment. The act of process and the administration of civil law are governed by the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Civil law can be further classified into Tort law, Family Law, Property Law, and Contract law.

Some examples of civil law are defamation, breach of contract, and a dispute between landlord and tenant.

- Common Law

A judicial precedent or a case law is common law. A law passed by the Supreme Court will be obligatory upon the courts and within the territory of India under Article 141 of the Indian Constitution.

A common law theory, Natural justice, often known as “Jus Natural,” encompasses statutory provisions for justice. Natural justice is identified with two constituents of a fair hearing. These are the rule against bias and the right to a fair hearing.

- Nemo judex in causa sua (Rule against Prejudice),

- Audi alteram partem (Rule of fair Hearing), and

- Reasoned decision

- are the rules of Natural Justice.

- Principle of Natural Justice has three points as under:

- Nobody can be punished unheard

- Nobody can be judge of his own case.

- Authorities must act without bias.

Features

Principles of natural justice are regarded as universal in nature. As they are universal in nature they are binding on all authorities including judiciary, executive and legislature, private individuals and all the organizations. The purpose of these principles is to exclude the elements of arbitrariness in decision and humanizing the decision making so that action must be supported by reasons.

The Apex Court held that these principles are implicitly found in Article 14 and 21 of the Constitution. They are so important for the functioning of the State that they are regarded as the part of the basic structure of Indian Constitution. The principles of Natural Justice have come out of the need of man to protect himself from the excesses of organized power. Man has always appealed to someone beyond his own creation. Such someone is the God and His Laws or Divine law or Natural law. Natural law is of ‘Higher Law of Nature’.

Natural law does not mean the law of the nature or jungle where lion eats the lamb and tiger eats antelope but a law in which the lion and lamb lie down together and the tiger hunt the antelope. Natural law is common sense justice. Natural laws are not codified. It is based on natural ideals and values which are universal.

Earlier Natural Law

Earliest form of natural law can be found in Roman philosophical expressions (Jus Naturale). It is used interchangeably with Divine Law, Jus Gentium and the Common Law of nations. Principles of Natural Justice are considered as the Basic Human Rights as they attempt to bring justice to parties naturally. Giving reasoned decisions is a postulate and principle of Natural Justice. No system of law can survive without these two basic pillars.

The doctrine of “Stare Decisis” is the principle for the common law. It is a Latin word that literally means “to stand by that which is decided.” The doctrine of Stare Decisis states the obligation of courts to follow the same principle or judgement established by previous decisions while ruling a case where the facts are similar. A judgement can override or alter a common law, but it cannot override or change the statute.

- Statutory Law

Statutory legislation refers to any written law approved by a legislative body to regulate the conduct of its citizens. The Central Government makes laws through Parliament, the state government makes laws through Vidhan Sabha, and the Local Government makes laws through municipalities. A bill is introduced in the legislature and for it to become an act voted upon by the members of both houses requires the assent of the President. The President of India has veto powers over his assent.

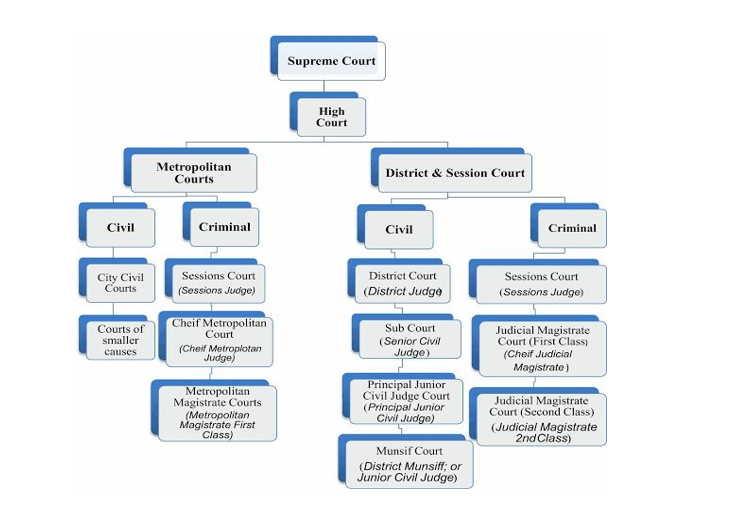

STRUCTURE OF THE INDIAN JUDICIAL SYSTEM

The judiciary system of India regulates the interpretation of the acts and codes, and dispute resolution, and promotes fairness among the citizens of the land. In the hierarchy of courts, the Supreme Court is at the top, followed by the High Courts and district courts.

- Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the apex body of the judiciary. It was established on 26th January 1950. The formulation of the Supreme Court of India is under Chapter IV of Part V of the Constitution of India. Article 145 of the Indian Constitution enshrines the establishment of Supreme Court Rules, 1966.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court covers 3 categories:

- Original (Article 131),

- Appellate (Article 133 and Article 134), and

- Advisory (Article 143).

The Chief Justice of India is the highest authority appointed under Article 126. The principal bench of the Supreme Court consisted of seven members including the Chief Justice of India. Presently, the number has increased to 34 including the Chief Justice of India due to the rise in the number of cases and workload. A Supreme Court judge is contravened from practising in any other court of law.

An Individual can seek constitutional remedies in the Supreme Court by filing a writ petition under Article 32. A law passed by the Supreme Court will be obligatory upon the courts and within the territory of India under Article 141 of the Indian Constitution.

- High court

The highest court of appeal in each state and union territory is the High Court. Article 214 of the Indian Constitution states that there must be a High Court in each state. The High Court has appellant, original jurisdiction, and Supervisory jurisdiction. However, Article 227 of the Indian Constitution limits a High Court’s supervisory power. The Constitution and its powers of a High Court are dealt with under Articles 214 to 231. In India, there are twenty-five High Courts, one for each state and union territory, and one for each state and union territory. Six states share a single High Court. The oldest high court in the country is Calcutta High Court, established on 2 July 1862.

The appointment of a judge of the High Court is dealt with under Article 217 of the Constitution. The High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Service) Act, 1954, deals with the regulations of salaries and services of a High Court judge.

An individual can seek remedies against violation of fundamental rights in High Court by filing a writ under Article 226.

- District courts

Chapter VI of Part VI of the Indian Constitution deals with subordinate courts. District Courts regulate matters of justice in a particular area or district chaired by a District judge. There are 672 district courts all over India. The appellate jurisdiction of the High court governs the ruling of the district court.

The district courts are divided into the Court of District Judge and the Court of Sessions Judge.

- Court of District Judge

A Court of District judge deals with cases of civil nature. It vests and exercises its powers from the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. It has original and appellate jurisdiction. The district courts have appellate jurisdiction over subordinate courts. Section 9 states that the courts have the power to try any case unless barred from doing it. Section 51 to 54 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 deals with procedure in execution. The civil district courts are categorised in ascending order,

- Junior Civil Judge,

- Principal Junior Civil Judge Court,

- Senior Civil Judge Court.

The appeal is filed under territorial jurisdiction, pecuniary jurisdiction, and Appellate Jurisdiction. Additional District Judge or Assistant District Judge is appointed depending upon the case and workload and has the same powers as a District Court Judge.

Under the pecuniary jurisdiction, a civil judge can try suits of valuation not more than Rupees two crore.

Under territorial jurisdiction, Section 16 to 20 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 deals with the territorial jurisdiction of courts. Cases are decided based on the nature of the property and within the local limits of the jurisdiction.

- Munsiff Courts

Munsiff courts are the lowest rank of courts in a district. It is usually under the control of the District Court of that region. The pecuniary and territorial jurisdiction limits are defined by the State Government.

- Court of Session

A Court of Sessions judge deals with criminal matters and is the highest authority in the district for criminal matters. It vests and exercises its powers from the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. Section 225 to Section 237 deals with the procedure for trial by a Public Prosecutor before a Court of Session. Section 29 deals with the sentences by a Chief Judicial Magistrate, Court of a Magistrate of the first class, and a Magistrate of the second class.

The Session Court is categorised as the court of Chief Judicial Magistrate and deals with matters punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding seven years but cannot be punished with a death sentence. The Court of a Magistrate of the first class deals with matters punishable for a term of not exceeding three years or a fine not exceeding ten thousand rupees, or both. A Judicial Magistrate of the second class deals with matters punishable with imprisonment not exceeding one year, a fine of one thousand rupees, or both. An Additional Sessions Judge or Assistant Sessions Judge is appointed depending upon the case and workload and has the same powers as a Session Court Judge. An Assistant Session Judge cannot give imprisonment of more than 10 years as per Section 28(3). The Additional Session judge can exercise the powers of a Sessions Judge vested into him by any general or special order of the Sessions Judge according to Section 400.

Section 366(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 lays down that a Session Court cannot impose a death penalty without the consultation of the High Court.

- Metropolitan courts

Section 16 states that Metropolitan courts are established in metropolitan cities in consultation with the High Court where the population is ten lakh or more. Section 29 states that Chief Metropolitan Magistrate has powers as Chief Judicial Magistrate and Metropolitan Magistrate has powers as the Court of a Magistrate of the first class.

FORM OF THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION

The Constitution of India has features of both federal and unitary constitutions and is quasi-federal in nature.

- The federal features of the Indian Constitution are:

Division of Powers

The federal system of the Indian Constitution decentralises powers between the state and the centre. Article 246 under the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution lays down three lists describing jurisdiction at each level:

- Union List: The power to make laws is vested in the Parliament of India. It consists of laws related to national importance such as defence, foreign relations, Naval, and military.

- State List: The state government has the right to make laws under this list. It consists of laws related to public order, public health, sanitation, agriculture, and transport.

- Concurrent List: The state government and the Government of India as a joint have the right to make laws under this list. It consists of laws related to criminal procedure, trade unions, education, industrial, and labour disputes.

Article 254 describes the doctrine of repugnancy. In case of any inconsistency between the laws of Parliament and the laws of the state on the Concurrent List, the laws of the Parliament will prevail.

Supremacy of the Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India is the supreme pillar of the laws in India. The core framework of the Indian Constitution cannot be modified or altered. Laws should be made concerning the Constitution of India. In case of any inconsistency with the Indian Constitution, the law shall be declared void by the power of judicial review vested to the High Court and Supreme Court.

In a landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), the Hon’ble Supreme Court defined the principle of basic structure and held that the basic structure of the Indian Constitution cannot be changed.

Independent judiciary

The Indian Constitution established the Supreme Court of India as the apex and independent judiciary to ensure the supremacy of the Indian Constitution. It regulates the framework of matters such as limits of power of central and state, fundamental rights and duties, and directive principles of state policy.

Written Constitution

The Constitution of India is the backbone for the rest of the acts. It is the longest written constitution and it consists of a Preamble, 470 Articles divided into 25 Parts with 12 Schedules.

Rigid Constitution

The Constitution of India is rigid in the provisions mentioned under it. The process for altering the provisions requires a special majority in the Parliament and the approval of at least half of the state legislatures.

Dual Government Polity

The Indian Constitution established dual government polity by setting up a Central and state Government. The Union government regulates the safeguarding of national issues whereas the state government focuses on regulating regional and local issues.

Bicameralism

The Indian Constitution established a system of bicameralism. It divides the legislative body into Lok Sabha (House of the People) and Rajya Sabha (Council of States). Lok Sabha or the lower house consists of representatives of people elected through a universal adult franchise whereas Rajya Sabha or the upper house is a permanent body that cannot be dissolved and is elected by the legislative members of the state.

- The unitary features of the Indian Constitution are:

Single citizenship

People of India enjoy single citizenship irrespective of in which state they reside. This ensured that the people of India are united as a whole. Articles 5 to 11 under Part II of the Indian Constitution deal with citizenship.

Strong centre

The Central Government has powers over the state government and carries residuary powers as well. The state government is bound by the laws of the Central Government.

Single Constitution

The Constitution of India is a uniform constitution that is applied to the whole of India. It is a framework of duties and powers of central and state government, fundamental rights and obligations of individuals, and directive principles of state policy that apply throughout India’s territory.

Appointment of governor

Article 155 states that by the assent of the President the governor of India is appointed. Article 156 states that the governor must hand over his resignation to the President.

Emergency powers

The emergency powers are vested with the President under Part XVIII, from Articles 352 to 360. The emergency is applied in the state of affairs when there is adversity to the security, sovereignty, unity, or integrity of a state.

SEPARATION OF POWERS

The separation of powers is categorized into 3 branches, legislative, executive, and judiciary, each has its own powers and responsibilities. The primary goal of the separation of powers was to prevent the misuse of authority by one organ of government. This model of separation of powers is known as trias political. The idea of this system was inspired by the model of Montesquieu in De l’esprit des Lois, 1747 (The Spirit of Laws,1747). In India, the separation of powers is not mentioned anywhere rigidly but can be found in parts of the Indian Constitution. The details of the three branches are as follows:

- Legislature

The legislative body is responsible for the enactment of the law. It comprises of Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha, and the President. It regulates the executive and the judiciary, the other two branches of law. Article 211 lays down restrictions on the legislature and refrains it from any discussion of the conduct of Judges of the Supreme Court or of a High Court.

- Executive

Part V of Chapter I deals with the executive organ. The executive body is in charge of government administration and policy execution in accordance with the principles of natural justice. The executive branch consists of the President under Article 53(1), the Vice President, the Prime Minister, and the council of ministers for advice under Article 74 to the President.

- Judiciary

The judiciary organ is responsible for the interpretation of the law and aiding justice in society. It comprises the Supreme Court, High Court, and all other subordinate courts. Article 50 of Part IV, Directive Principles of State Policy, establishes the separation of the judiciary and the executive. However, the executive organ is responsible for the appointment of the judiciary. Article 122 and Article 212 state that courts do not have the power to examine Parliamentary proceedings and legislative proceedings respectively.

System of checks and balances

The system of checks and balances regulates the prevention of arbitrary and inconsistency with the powers vested to the organs of the government. The goal behind the checks and balances system is to guarantee that the branches of government check and balance each other so that no branch of the government becomes too authoritative. It promotes efficiency and specialization between the organs of the government. The judiciary organ has the power to exercise judicial review over the acts of legislative and executive. The Judiciary must ensure that it exercises within the limits of the law. The executive organ is responsible for the appointment and removal of Judges in the judiciary organ and the executive is answerable to the legislative organ.

General legislative process.

- A draft of a legislative proposal is a bill. A Minister can introduce a Government Bill or a Private Member can introduce a Private Member’s Bill in either the Lok Sabha or the Rajya Sabha. To introduce a bill in the House, a Member-in-Charge must first obtain approval from the Speaker of the House. This procedure is known as “first reading”.

- In case the introduction to the bill is opposed, the speaker may allow a briefing by the members opposing it. When a bill is objected to on the ground that it exceeds legislative power, the speaker may allow a discussion and voting in the House.

- After being introduced in the parliament, a bill is usually published in the public gazette. Under certain conditions, a bill can be published in the public gazette without being introduced in the house with the speaker’s approval. The committee may seek expert advice or public opinion, but it must ensure that the general principles and provisions are taken into consideration while drafting the report and submitting it to the House after completion.

- There are two steps to the second reading stage. The first stage consists of a discussion of the bill’s underlying principle. It is up to the House to recommend the bill to a Select Committee or Joint Committee, circulate it for public opinion, or pass it. When a bill is issued for public input, it is not authorized to move it for a motion of consideration. The second stage consists of examining the Bill clause by clause or as reported by a select or joint committee. The applicable amendments that are moved but not withdrawn are voted on. If the amendments obtain a majority of votes, they form part of the law.

- The Member-in-Charge can move the bill for the third stage once the second stage is completed. At this stage, the debate about whether the Bill should be supported or opposed takes place.

- After a Bill has been passed in one House, it is sent to other house for consensus and goes through the above-mentioned stages with the exception of the introduction stage. If one house passes a bill but the other rejects it, or the houses reject the bill’s amendments, or more than six months have passed from the date of receipt of the bill by one house, the president may call a joint sitting of the two houses to resolve the stalemate. The bill is considered to be passed by both Houses if a majority of the total number of members of both Houses vote in favour of it and its amendments. However, there cannot be a joint sitting for amendment in the Constitution.

- Ordinary bills require only a simple majority. Each house must vote with a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members present in order to revise the constitution.

- After the Houses of Parliament have passed a bill, it is delivered to the President for his approval. After the President signs a bill into law, it becomes an act.

RULE OF LAW

Rule of law means “the law rules”. Rule of law refers to “a government based on the principles of law and not of men”. In its ideological sense, the concept of rule of law represents an ethical code for the exercise of public power, the basic postulates of which are equality, freedom & accountability. It refers a ‘climate’ of legal order which is just & reasonable. Every executive, legislative & judicial exercise of power must depend on this ideal for its validity.

It means that ‘Law shall prevail and not an individual’. Law shall be supreme and there cannot be any individual who is above the law. This is what is called the Doctrine of Rule of Law i.e. “Law governs & not individuals”.

The individuals (President, PM & Council of Ministers) may be the means of governance but even such individuals have to act under the law. Such individuals are not supreme rather the Constitution is the supreme.

The Rule of Law implies that the government has to exercise its powers in such a manner in which:

- The dignity of an individual is upheld

- The object of social welfare & justice can be achieved.

- The unity of the individual and the integrity of the nation can be promoted.

- There is no discrimination between people in matters of sex, religion, caste or race etc.

- Equality exists.

History of Rule of Law

Rule of law is existing since ancient times. During that period also, Law was above than the king. Everyone had to follow the law.

No one was above the law.

In Dharma sastras– it is mentioned that

“ parties must be heard. No decision can be given behind the back of the parties. The judges must not have any bias or interest in the cause. They must pronounce judgment with reasons.”

Three Pillars of Rule of Law given by A.V Dicey

According to A.V. Dicey, rule of law means the ‘absolute supremacy of regular law’. Dicey’s concept of rule of law means ‘no influence of arbitrary powers and thus exclusion of liberty, equality before the law and protection of individual liberties. Dicey’s theory has three pillars based on the concept that “a government should be based on principles of law and not of men”. These are:

- Supremacy of law

As per the first postulate, rule of law refers to the lacking of arbitrariness or wide discretionary power. In order to understand it simply, every man should be governed by law.

According to Dicey, English men were ruled by the law and the law alone and also where there is room for arbitrarinessand that in a republic no less than under a monarchy discretionary authority on the part of the Government must mean insecurity for legal freedom on the part of its subjects. There must be absence of wide discretionary powers on the rulers so that they cannot make their own laws but must be governed according to the established laws.

- Equality before law

According to the second principle of Dicey, equality before law and equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of land to be administered by the ordinary law courts and this principle emphasizes everyone which included government as well irrespective of their position or rank. But such element is going through the phase of criticisms and is misguided. As stated by Dicey, there must be equality before law or equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of land. French legal system of Droit Administrative was also criticized by him as there were separate tribunals for deciding the cases of state officials and citizens separately.

- Predominance of Legal Spirit

According to the third principle of Dicey, general principles of the Indian Constitution are the result of the decisions of the Indian judiciary which determine to file rights of private persons in particular cases. According to him, citizens are being guaranteed the certain rights such as right to personal liberty and freedom from arrest by many constitutions of the states (countries). Only when such rights are properly enforceable in the courts of law, those rights can be made available to the citizens. Rule of law as established by Dicey requires that every action of the administration must be backed and done in accordance with law. In modern age, the concept of rule of law oppose the practice of conferring discretionary powers upon the government and also ensures that every man is bound by the ordinary laws of the land as well as signifies no deprivation of his rights and liberties by an administrative action.

RULE OF EQUITY

In law, the term “equity” refers to a particular set of remedies and associated procedures involved with civil law. These equitable doctrines and procedures are distinguished from “legal” ones. A court will typically award equitable remedies when a legal remedy is insufficient or inadequate.

In modern practice, perhaps the most important distinction between law and equity is the set of remedies each offers. The most common civil remedy a court of law can award is monetary damages. Equity, however, enters injunctions or decrees directing someone either to act or to forbear from acting.

- Difference between Law and Equity

Equity allows courts to apply justice based on natural law and on their discretion. The most distinct difference between law and equity lies in the solutions that they offer.

- Concept of Equity

It is generally agreed that equity implies a need for fairness (not necessarily equality) in the distribution of gains and losses and the entitlement of everyone to an acceptable quality and standard of living. The concept of equity is well entrenched in international law.

- Origin

Two distinct system of law were administered by different tribunals at the same time in England till the year 1875. The older system was the Common Law and it was administered by the King’s Benches. A modern body of legal doctrine was developed and administered in the Court of Chancery as supplementary to and coercive of the old law, was the law of Equity. The two systems of law were almost identical and in harmony leading to maxim “Equity follows the law”. In other words the rules already established in the old Courts were adopted by the Court of Chancery and incorporated into the system of equity unless there were sufficient reasons for rejection or modification. In case of conflict, the rule of Chancery prevailed.

- Nature

- Equity follows the law. In case of conflict between law and equity, law prevails.

- An equitable right arises when a right vested in one person by the law should be vested in another in the view of equity as a matter of conscience.

- Where equities are equal, which is first in time will prevail.

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION

- The expression ‘Public Interest Litigation’ has been borrowed from American jurisprudence, where it was designed to provide legal representation to previously unrepresented groups like the poor, the racial minorities, unorganised consumers, citizens who were passionate about the environmental issues, etc.

- Public interest Litigation (PIL) means litigation filed in a court of law, for the protection of “Public Interest”, such as Pollution, Terrorism, Road safety, Constructional hazards etc. Any matter where the interest of public at large is affected can be redressed by filing a Public Interest Litigation in a court of law.

- Public interest litigation is not defined in any statute or in any act. It has been interpreted by judges to consider the intent of public at large.

- Public interest litigation is the power given to the public by courts through judicial activism. However, the person filing the petition must prove to the satisfaction of the court that the petition is being filed for a public interest and not just as a frivolous litigation by a busy body.

- The court can itself take cognizance of the matter and proceed suo motu or cases can commence on the petition of any public spirited individual.

Some of the matters which are entertained under PIL are:

- Bonded Labour matters

- Neglected Children

- Non-payment of minimum wages to workers and exploitation of casual workers

- Atrocities on women

- Environmental pollution and disturbance of ecological balance

- Food adulteration

- Maintenance of heritage and culture

Genesis and Evolution of PIL in India: Some Landmark Judgements

The seeds of the concept of public interest litigation were initially sown in India by Justice Krishna Iyer, in 1976 in Mumbai Kamagar Sabha vs. Abdul Thai.

The first reported case of PIL was Hussainara Khatoon vs. State of Bihar (1979) that focused on the inhuman conditions of prisons and under trial prisoners that led to the release of more than 40,000 under trial prisoners.

- Right to speedy justice emerged as a basic fundamental right which had been denied to these prisoners. The same set pattern was adopted in subsequent cases.

A new era of the PIL movement was heralded by Justice P.N. Bhagawati in the case of S.P. Gupta vs. Union of India. In this case it was held that “any member of the public or social action group acting bonafide” can invoke the Writ Jurisdiction of the High Courts (under article 226) or the Supreme Court (under Article 32) seeking redressal against violation of legal or constitutional rights of persons who due to social or economic or any other disability cannot approach the Court.

By this judgment PIL became a potent weapon for the enforcement of “public duties” where executive action or misdeed resulted in public injury. And as a result any citizen of India or any consumer groups or social action groups can now approach the apex court of the country seeking legal remedies in all cases where the interests of general public or a section of the public are at stake.

Justice Bhagwati did a lot to ensure that the concept of PILs was clearly enunciated. He did not insist on the observance of procedural technicalities and even treated ordinary letters from public-minded individuals as writ petitions.

The Supreme Court in Indian Banks’ Association, Bombay & Ors. Vs. M/s Devkala Consultancy Service and Ors held :- “In an appropriate case, where the petitioner might have moved a court in her private interest and for redressal of the personal grievance, the court in furtherance of Public Interest may treat it a necessity to enquire into the state of affairs of the subject of litigation in the interest of justice.” Thus, a private interest case can also be treated as public interest case.

M.C Mehta vs. Union of India: In a Public Interest Litigation brought against Ganga water pollution so as to prevent any further pollution of Ganga water. Supreme Court held that petitioner although not a riparian owner is entitled to move the court for the enforcement of statutory provisions, as he is the person interested in protecting the lives of the people who make use of Ganga water.

Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan: The judgement of the case recognized sexual harassment as a violation of the fundamental constitutional rights of Article 14, Article 15 and Article 21. The guidelines also directed for the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013.

Factors Responsible for the Growth of PIL in India

- The character of the Indian Constitution. India has a written constitution which through Part III (Fundamental Rights) and Part IV (Directive Principles of State Policy) provides a framework for regulating relations between the state and its citizens and between citizens inter-se.

- India has some of the most progressive social legislations to be found anywhere in the world whether it be relating to bonded labor, minimum wages, land ceiling, environmental protection, etc. This has made it easier for the courts to haul up the executive when it is not performing its duties in ensuring the rights of the poor as per the law of the land.

- The liberal interpretation of locus standi where any person can apply to the court on behalf of those who are economically or physically unable to come before it has helped. Judges themselves have in some cases initiated suo moto action based on newspaper articles or letters received.

- Although social and economic rights given in the Indian Constitution under Part IV are not legally enforceable, courts have creatively read these into fundamental rights thereby making them judicially enforceable. For instance the “right to life” in Article 21 has been expanded to include right to free legal aid, right to live with dignity, right to education, right to work, freedom from torture, bar fetters and hand cuffing in prisons, etc.

- Judicial innovations to help the poor and marginalised: For instance, in the Bandhua Mukti Morcha, the Supreme Court put the burden of proof on the respondent stating it would treat every case of forced labor as a case of bonded labor unless proven otherwise by the employer. Similarly in the Asiad Workers judgment case, Justice P.N. Bhagwati held that anyone getting less than the minimum wage can approach the Supreme Court directly without going through the labor commissioner and lower courts.

In PIL cases where the petitioner is not in a position to provide all the necessary evidence, either because it is voluminous or because the parties are weak socially or economically, courts have appointed commissions to collect information on facts and present it before the bench.

Who Can File a PIL and Against Whom?

Any citizen can file a public case by filing a petition:

- Under Art 32 of the Indian Constitution, in the Supreme Court.

- Under Art 226 of the Indian Constitution, in the High Court.

- Under sec. 133 of the Criminal Procedure Code, in the Court of Magistrate.

However, the court must be satisfied that the Writ petition fulfils some basic needs for PIL as the letter is addressed by the aggrieved person, public spirited individual and a social action group for the enforcement of legal or Constitutional rights to any person who are not able to approach the court for redress.

A Public Interest Litigation can be filed against a State/ Central Govt., Municipal Authorities, and not any private party. The definition of State is the same as given under Article 12 of the Constitution and this includes the Governmental and Parliament of India and the Government and the Legislature of each of the States and all local or other authorities within the territory of India or under the control of the Government of India.

Significance of PIL

- The aim of PIL is to give to the common people access to the courts to obtain legal redress.

- PIL is an important instrument of social change and for maintaining the Rule of law and accelerating the balance between law and justice.

- The original purpose of PILs have been to make justice accessible to the poor and the marginalised.

- It is an important tool to make human rights reach those who have been denied rights.

- It democratises the access of justice to all. Any citizen or organisation who is capable can file petitions on behalf of those who cannot or do not have the means to do so.

- It helps in judicial monitoring of state institutions like prisons, asylums, protective homes, etc.

- It is an important tool for implementing the concept of judicial review.

- Enhanced public participation in judicial review of administrative action is assured by the inception of PILs.

Certain Weaknesses of PIL

- PIL actions may sometimes give rise to the problem of competing rights. For instance, when a court orders the closure of a polluting industry, the interests of the workmen and their families who are deprived of their livelihood may not be taken into account by the court.

- It could lead to overburdening of courts with frivolous PILs by parties with vested interests. PILs today has been appropriated for corporate, political and personal gains. Today the PIL is no more limited to problems of the poor and the oppressed.

- Cases of Judicial Overreach by the Judiciary in the process of solving socio-economic or environmental problems can take place through the PILs.

- PIL matters concerning the exploited and disadvantaged groups are pending for many years. Inordinate delays in the disposal of PIL cases may render many leading judgments merely of academic value.

LEGAL SERVICES AND LOK ADALATS

It is very difficult to reach the benefits of the legal process to the poor and to protect them against injustice. Therefore, it is urgently required to introduce dynamic and comprehensive legal service programme with a view to deliver justice to the poor and needy person. Legal aid is the provision of assistance to people otherwise unable to afford legal representation and access to the court system.

History Of Legal Aid Services

The earliest Legal Aid movement appeared in the year 1851 when some enactment was introduced in France for providing legal assistance to the poor. In Britain, the history of the organised efforts on the part of the State to provide legal services to the poor and needy dates back to 1944, when Lord Chancellor, Viscount Simon appointed Rushcliffe Committee to enquire about the facilities existing in England and Wales for giving legal advice to the poor and to make recommendations as appear to be desirable for ensuring that persons in need of legal advice are provided the same by the State. Since 1952, the government of India also started addressing to the question of legal aid for the poor in various conferences of Law Ministers and Law Commissions. In 1960, some guidelines were drawn by the government for legal aid schemes. In different States legal aid schemes were floated through Legal Aid Boards, Societies and LawD In 1980, a Committee at the national level was constituted to oversee and supervise legal aid programmes throughout the country under the chairmanship of Hon. Mr. Justice P.N. Bhagwati, then the Judge of the Supreme Court of India. This Committee came to be known as CILAS (Committee forI Legal Aid Schemes) and started monitoring legal aid activities throughout the country.

Article 39-A of the Constitution of India provides that State shall ensure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity, and shall in particular, provide free legal aid, by suitable legislation or schemes or in any other way, to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disability. Articles 14 and 22(1) also make it obligatory for the State to ensure equality before law and a legal system which promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity to all. Legal aid strives to ensure that constitutional pledge is fulfilled in its letter and spirit and equal justice is made available to the poor, downtrodden and weaker sections of the society.

Article 39-A of Constitution of India emphasises that free legal service is an inalienable element of ‘reasonable, fair and just’ procedure for without it a person suffering from economic or other disabilities would be deprived of the opportunity for securing justice. The right to free legal services is, therefore, clearly an essential ingredient of ‘reasonable, fair and just, procedure for a person accused of an offence and it must be held implicit in the guarantee of Article-21 of the Constitution. This is a constitutional right of every accused person who is unable to engage a lawyer and secure legal services on account of reasons such as poverty, indignant situation and the State is under a mandate to provide a lawyer to an accused person if the circumstances of the case and the needs of justice so requires, provided, of course, the accused person does not object to the provision of such lawyer.

Legal Services Authority Act, 1987

- Objectives of Legal Services Authority Act

Under Article 39A of the Constitution of India, free legal aid and equal justice are provided to all citizens by appropriate legislation, schemes or other means to ensure that no citizen is denied access to justice on the basis of economic disadvantage or in any other way. The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 was enacted as a consequence of this constitutional provision with the primary objective of providing free and competent legal services to the weaker sections of society in the country.

- Types of services under Legal Services Authority Act

The Act provides many types of legal services to the general public:

- Free legal awareness

This Act is primarily intended for the public to make them aware of laws and schemes issued by public authorities. The Legal Service Authority teaches some portions of the rules of law to the individuals. Legal camps and legal aid centres are organized by authorities so that the general public can seek advice from the legal aid centres located near their homes or places of work. The legal guides and centres can help address the grievances of ordinary people as well.

- Free legal aid counsel

A person who wants to defend or file a case in a court of law but does not have the means to hire an advocate can seek the assistance of a free legal aid attorney. The Act states that free legal aid counsel is available, and the Council is responsible for assisting needy individuals to obtain justice. By adopting and establishing this philosophy, the Indian Courts should be freed from the burden of adjudicating the cases.

- Authorities Under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987

The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 provides that the Central Government shall constitute a body to be called the National Legal Services Authority toe the powers and perform the functions conferred on , or assigned to, the Central Authority under this Act. A nationwide network has been envisaged under the Act for providing legal aid and assistance. National Legal Services Authority is the apex body constituted to lay down policies and principles for making legal services available under the provisions of the Act and to frame most effective and economical schemes for legal services. It also disburses funds grants to State Legal Services Authorities and NGOs for implementing legal aid schemes and programmes. The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 provides for the constitution of ‘State Legal Services Authority’. In every State a State Legal Services Authority is constituted to give effect to the policies and directions of the Central Authority (NALSA) and to give legal services to the people and conduct ‘Lok Adalats’ in the State. State Legal Services Authorityi headed by the Chief Justice of the State High Court who is its Patron-in-Chief. A serving or retired Judge of the High Court is nominated as its Executive Chairman.

‘District Legal Services Authority’ is constituted in every District to implement Legal Aid Programmes and Schemes in the District. The District Judge of the District is its ex-officio Chairman.

‘Taluk Legal Services Committees’ are also constituted for each of the Taluk or Mandal or for group of Taluk or Mandals to coordinate the activities of legal services in the Taluk and to organise Lok Adalats. Every Taluk Legal Services Committee is headed by a senior

Civil Judge operating within the jurisdiction of the Committee who is its ex-officio Chairman.

The main responsibilities of NALSA are the following:

- Through legal aid camps, the organization promotes legal aid in slums, rural and labour colonies, as well as disadvantaged areas. It plays an important role in providing education about the rights and needs of the people who live in such areas. Lok Adalats are also formed by the authority to settle disputes between these people.

- Amongst other things, it is primarily concerned with providing legal services through clinics in law colleges, universities, etc.

- Arbitration, mediation, and conciliation are all methods that are used by these organizations to settle disputes.

- The organisation provides grant aid to institutions that provide social services at the grassroots level to marginalised communities from various parts of the country.

- Research activities are also conducted to improve legal services for the poor.

- Ensures that citizens commit to the fundamental duties they have been entrusted with.

- As part of the proper implementation of the schemes and programmes, they tend to evaluate the effectiveness of the actions taken for the legal aid problems at specific intervals so that the correct functions are being performed.

- Through the policy and scheme they laid down, the body ensures that the legal services could be made available to the general public. Through these schemes, the body is able to provide the most economical and effective legal services

- Financial matters are handled by this body, and the funds allocated by it are allocated to respective district and state legal services authorities.

In NALSA v. Union of India (2014) the National Legal Services Authority of India (NALSA) filed this case to recognize those who are outside the binary gender distinction, including individuals who identify as “third gender”. There was a question that the Court had to address regarding the recognition of people who do not fit into the male/female binary as “third gender” individuals. During the discussion, the panel deliberated whether ignoring non-binary gender identities constitutes an infringement of Indian Constitutional rights. For developing its judgment, the panel referred to an “Expert Committee on Transgender Issues” established under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

- Eligibility criteria for free legal aid

There was even an item on the committee’s (headed by Justice PN Bhagwati) agenda on the eligibility criteria for the people to qualify for free legal aid, which has been also mentioned in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 under Section 304 to provide free and competent legal assistance to a marginalised member of the society at the expense of the state. As established in Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979), legal aid will be provided at the expense and cost of the state to marginalised groups within society, and the state is required to make such assistance available to the accused.

In a similar vein, the Supreme Court has also ruled in Suk Das v. Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh (1986) that an accused who cannot afford legal aid may have his or her conviction set aside on socio-economic grounds.

The following are the people eligible for free legal aid under Section 12 of the Act:

- A member of a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe;

- A victim of trafficking in human beings or beggars as referred to in Article 23 of the Constitution;

- A woman or a child;

- A person with a disability as defined in Section 2(i) of the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995;

- A person under circumstances of undeserved want such as being a victim of a mass disaster, ethnic violence, caste atrocity, flood, drought, earthquake or industrial disaster; or

- An industrial workman; or

- In custody, including custody in a protective home within the meaning of Section 2(g) of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 or in a juvenile home within the meaning of Section 2(j) of the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986 or in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home within the meaning of Section 2(g) of the Mental Health Act, 1987; or

- In receipt of annual income less than rupees nine thousand or such other higher amount as may be prescribed by the State Government, if the case is before a court other than the Supreme Court, and less than rupees twelve thousand or such other higher amount as may be prescribed by the Central Government, if the case is before the Supreme Court.

Lok Adalat

‘Lok Adalat’ is a system of conciliation or negotiation. It is also known as ‘people’s court’. It can be understood as a court involving the people who are directly or indirectly affected by the dispute or grievance. ‘Lok Adalat’, established by the government settles dispute through conciliation and compromise.

The First ‘Lok Adalat’ was held in Chennai in 1986. ‘Lok Adalat’ accepts the cases which could be settled by conciliation and compromise and pending in the regular courts within their jurisdiction.

Lok Adalat under Legal Services Authority Act, 1987

Section 19 of the Act provides for the establishment of Lok Adalats. Legal service authorities at all levels, including the central, state, and district levels, shall hold Lok Adalats. Lok Adalats serve as an alternate dispute resolution system. Their purpose is to settle cases that are pending or that have not been heard in the courts. It consists of judicial officers or an authorized person under the jurisdiction of the state, central government, or local government. Following the conciliation of disputes between the parties and the agreement of the parties, the award is handed down by conciliators in accordance with Section 21 of the Act. The award has the same legal effect as a court decision.

Scope of Lok Adalat

Unlike the Supreme Court, Lok Adalat is extremely broad to incorporate most of the cases pending before it as well as new cases that will be filed in the near future to be settled. The Lok Adalat does not have jurisdiction over cases relating to offences that cannot be compounded under any law. The Lok Sabha does not refer such matters to committees without giving the other party a reasonable opportunity to be heard. The Lok Adalat proceeds to resolve any case referred to it and tries to negotiate a mutually acceptable outcome between the parties involved with the case. Whenever a Lok Adalat decides a case before it, it adopts the most extreme efforts for a trade-off or settlement. The following points elaborate on the scope of Lok Adalats:

- If no settlement or compromise is reached by the parties after the Lok Adalat passes, no order is given.

- A reference will be sent automatically to the Court that drew up the reference for disposition. Those involved in the dispute are urged to seek redressal in courts.

- If the terms proposed by the bench do not satisfy the parties, the Lok Adalat cannot be forced to compromise or reach a settlement. Orders from Lok Adalats are definitive and restrict the parties.

- An order passed by a judge is a satisfactory means of stopping the proceedings that demand justice.

- Lok Adalats have enough powers under the Act to make justice without compromising the quality of their awards. The Lok Adalat’s final order is considered judicial since it is given the status of a decree.

- A Civil Court recognizes it as a form of evidence and is given the power to summon, discover, and get an affirmation.

In the case of P.T. Thomas v. Thomas Job (2005), the Apex Court specifically explained what Lok Adalat is. According to the Court, Lok Adalat is an ancient form of adjudicating system that once predominated in India, and its validity has not been questioned even today. According to Gandhian principles, the term Lok Adalat means “People’s Court”. It is an essential component of alternative dispute resolution. If the dispute is resolved at Lok Adala, there is no court fee, and if it is already paid, the fee will be refunded.

According to the case of B.P. Moideen Sevamandir and others v. AM Kutty Hassan (2008), the parties can communicate directly through their attorneys, which is far more convenient than speaking in a regular courtroom. Because Lok Adalats are dynamic, they are able to balance the interests of both parties and pass orders that both sides find acceptable.

Need of Lok Adalats

As we know that justice delayed is justice denied. This statement becomes true if we see the backlog of pending cases before courts of different hierarchy. It resulted into delay Justic in India. Mounting arrears of cases has brought judiciary and the judicial process at the verge of collapse. In this given state of affairs the mechanism of Lok Adalats is the only option left with the people resort to for availing cheap and speedy justice. Lok Adalats effectively deal with the magnitude of arrears of cases. ‘Lok Adalat’ has in view the social goals of ending bitterness rather than pending disputes restoring peace in the family, community and locality.

So ‘Lok Adalat’ is favorable to poor sections of the society.

Functions of Lok Adalat

The following are the functions of Lok Adalat:

- Lok Adalat members should be impartial and fair to the parties.

- Lok Adalat is responsible for handling pending cases in court. In the case of a Lok Adalat settlement, the court fee paid to the court on the petition will be reimbursed

- When filing a dispute with Lok Adalat, you do not have to pay a court fee.

Types of Lok Adalat

Lok Adalats can take the following forms:

- National level Lok Adalat

The Lok Adalat held at the national level is held regularly throughout the country at the Supreme Court level and taluk level, where thousands of cases are disposed of. Every month a different topic is discussed in this Adalat.

- Permanent Lok Adalat

The body is governed by Section 22B of the Act. There is a mandatory pre-litigation mechanism in Permanent Lok Adalat that settles disputes concerning public utilities such as transport, telegraph, postal service, etc. As a result of the case Abdul Hasan and National Legal Services Authority v. Delhi Vidyut Board and other (1999), the courts directed that permanent Lok Adalats be established.

Permanent Lok Adalats are charged with resolving public utility disputes quickly. Therefore, if parties neglect to show up at the settlement or compromise, then it has a further advantage of choosing the dispute based on merit. In this way, the possibility of postponement in the resolution of questions is eliminated. Rather than following the formal procedure for resolving disputes, it is bound to follow the principle of natural justice in order to save time.

- Mobile Lok Adalat

Mobile Lok Adalat is a method of settling disputes that travels from place to place. Over 15.14 lakh Lok Adalats have been held in the country as of 30th September 2015, and over 8.25 crore cases have been settled.

- Mega Lok Adalat

The Mega Lok Adalat is an ad hoc body that is constituted at the state level on a single day in all courts.

- Daily Lok Adalat

On a daily basis, these Lok Adalats are held.

- Continuous Lok Adalat

It is held continuously for a specific number of days.

Jurisdiction of Lok Adalats

Lok Adalats fall under the jurisdiction of the courts which organize them, thus, they cover any cases heard by that Court under its jurisdiction. This jurisdiction does not apply to cases regarding offences which are not compoundable by law and the Lok Adalats cannot resolve these cases. The respective courts may accept cases presented to them by parties concurring that the dispute should be referred to the Lok Adalat. The Courts may accept such cases in situations where one party makes an application to the court for the referral of the case to the Lok Adalat and the court might consider that there is a possibility of compromise through the Act.

PLEA BARGAINING- MEANING

“Plead Guilty and ensure Lesser Sentence” is the shortest possible meaning of Plea Bargaining. Plea Bargaining fostered by the Indian Legislature is actually the child of the West. The concept has been very much alive in the American System in the 19th century itself. Plea Bargaining is so common in the American System that every minute a case is disposed in the American Criminal Court by way of guilty plea. England, Wales, Australia and Victoria also recognises ‘Plea Bargaining’.

‘Plea Bargaining’ can be defined as “Pre-Trial negotiations between the accused and the prosecution during which the accused agrees to plead guilty in exchange for certain concessions by the prosecution”. It gives criminal defendants the opportunity to avoid sitting through a trial risking and conviction on the original more serious charge. For example, a criminal defendant charged with a theft charge, the conviction of which would require imprisonment in state prison, may be offered the opportunity to plead guilty to a theft charge, which may not carry jail term.

Types of ‘Plea Bargaing’

‘Plea Bargaining’ may be divided into three broad types:

- ‘Charge Bargaining’ is a common and widely known form of plea. It involves a negotiation of the specific charges or crimes that the defendant will face at trial. Usually, in return for a plea of guilty to a lesser charge, a prosecutor will dismiss the higher or other charge(s). For example, in return for dismissing charges for first-degree murder, a prosecutor may accept a guiltyp for manslaughter (subject to court approval).

- ‘Sentence Bargaining’ involves the agreement to a plea of guilty in return for a lighter sentence. It saves the prosecution the necessity of going through trial and proving its case. It provides the defendant with an opportunity for a lighter sentence.

- ‘Fact Bargaining’ is the least used in a prosecution in which the Prosecutor agrees not to reveal any aggravating factual circumstances to the court because that would lead to a mandatory minimum sentence or to a more severe sentence under sentencing guidelines.

JUDICIAL REVIEW

Legislatures, one of the organs of the government, is vested with the power to make laws, which is, however, not absolute in nature. Because it does not become absolute that no one can challenge any arbitrary law, a concept known as judicial review came into existence which is the process wherein the Judiciary review the validity of laws passed by the legislature.

The power of judicial review comes from the Constitution of India itself (Article 13) & it is evoked to safeguard & enforce the fundamental rights under Part III of the Constitution. Article 13 prohibits the Parliament and the state legislatures from making laws that “may take away or abridge the fundamental rights” guaranteed to the citizens of the country & the term ‘law’ includes any “Ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usage” having the force of law in India.

Examples of Judicial Review: Section 66A of the IT Act was struck down as it was against the Fundamental Rights under the Indian Constitution.

JUDICIAL ACTIVISM

Judicial activism refers to the use of judicial authority by the Judiciary to define and enforce what is for the benefit of society. Historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. coined this term in 1947, and its foundation in India was laid down by Justice V.R Krishna Iyer, Justice P.N Bhagwati, Justice O.Chinnappa Reddy, and Justice D.A Desai.

Judiciary cannot function as legislature, but by the concept of judicial activism, it has successfully brought reforms, new concepts, policies etc.

However, too much interference by the Judiciary in this process will become judicial overreach.

Examples of Judicial Activism-

- Mechanisms with no constitutional backing like Public Interest Litigation, not proposed by the Legislature, but the Judiciary came up with this concept. It has strict locus standi; anyone can file PIL, which is filed in the form of writ petition but only in the High Courts and Supreme Court.

- Appointment of Judges by the Collegium system in which senior most Judges appoints another Judge is considered judicial activism by the Judiciary.

- Reforms in Cricket: The Supreme Court has been trying its best to restructure the Board for the Control of Cricket in India (BCCI) although, the BCCI is a private body. SC had also set up a Mudgal committee and the Lodha Panel to investigate the betting charges and suggest reforms which must be adhered to.

- SIT on Black money: The Supreme Court ordered the UPA government to set up Special Investigation Team (SIT) to investigate black money. Though the UPA government did not take action on this decision, the NDA government has now fulfilled the task.

Maneka Gandhi v. UOI (1978), The court iterated the term ‘procedure established by law’ under Article 21 of the Constitution by repositioning it as ‘due process of law’ meaning that the procedure which is established by the law must be just, fair and reasonable. It is the legal requirement that the state must respect all of the legal rights owed to a person.

Kesavananda Bharati case (1973): The Supreme Court of India declared that the executive had no right to interfere and tamper with the basic structure of the constitution.

Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra (1983): A letter by a Journalist addressed to the Supreme Court addressing the custodial violence of women prisoners in Jail. The court treated that letter as a writ petition and took cognisance of that matter.

I.C. Golaknath & Ors vs State Of Punjab & Anr. (1967): The Supreme Court declared that Fundamental Rights enshrined in Part III are immune and cannot be amended by the legislative assembly.

Criticism of Judicial Activism

It created a controversy over the supremacy between Parliament and Supreme Court. It is alleged to disturb the delicate principle of separation of powers & checks and balances.

JUDICIAL OVERREACH

There is a very thin line between Judicial activism and Judicial Overreach. In layman’s term, when Judicial activism surpasses its limits and becomes Judicial adventurism, it is known as Judicial Overreach. When the judiciary oversteps its powers, it may intervene with the proper functioning of the legislative or executive organs of government.

This is highly undesirable under Indian democracy as there has to be a proper separation of power between the three organs of the government, which even forms the feature of our Indian Constitution. So, it destroys the spirit of separation of powers.

Examples of Judicial Overreach: What makes any action activism or overreach is based upon individual’s perspectives. But generally speaking, striking down of NJAC bill and the 99th constitutional amendment and bringing collegium system for appointment of judges, or the order passed by the Allahabad High Court making it compulsory for all Bureaucrats to send their children to government school or misuse of the power to punish for contempt of court etc. are all considered as Judicial Overreach.

Difference between Judicial Review, Judicial Activism and Judicial Overreach

JUDICIAL RESTRAINT

A concept under which the judges power is limited to strike down a law as the proponents of judicial restraint have mostly stated that the Supreme Court has taken the position of the Legislature through its activism. It has also been argued that the Supreme Court has obviously overstepped its bounds of the other parts of government. In Judicial restraint, Judges should look to the original intent of the writers of the Constitution.

Issues with the Indian legal system

One of the most crucial challenges with the Indian judicial system is the delay of cases. The major source of pendency is the increasing number of new cases and the slow rate at which they are resolved. Over 4.7 crore lawsuits are pending in courts at all levels of the judiciary as of May 2022. Nearly 1,82,000 cases have been outstanding for more than 30 years, with 87.4 per cent in subordinate courts and 12.4 per cent in High Courts. According to data from the Department of Justice’s National Judicial Data Grid database, courts recorded a 27 per cent increase in pendency between December 2019 and April 2022.

Presently, there is an inadequate number of judges available to resolve disputes. Statistics of the Department of Justice show that there are 400 vacancies with a working force of 708 as of June 2022 for the Judges in the Supreme Court of India and the High Courts which is not sufficient to clear the backlog of pending cases in India.

Reforms needed in the Indian legal system