This article is written by Zeeshan Rahman of Centre for Juridical Studies, Dibrugarh University, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

The article delves into the symbiotic relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and stakeholders, unveiling a transformative shift from profit-centric models to holistic commitments. CSR, founded on ethical responsibility, environmental sustainability, philanthropy, and economic responsibility, challenges conventional business paradigms. Stakeholder theory emerges as a guiding framework, emphasizing the pivotal role stakeholders play in CSR success. The dynamic interplay between businesses and stakeholders, including shareholders, non-profit organizations, and international bodies like the United Nations, underscores the multifaceted nature of responsible corporate practices. Challenges in CSR implementation, including aligning business and employee goals, transparent communication, and maintaining stakeholder consensus, highlight the strategic importance of incorporating stakeholder theory. The article also navigates the conflicts arising from diverse stakeholder interests, particularly between insiders prioritizing personal affiliations and non-affiliated shareholders emphasizing broader value. Ultimately, the synthesis of CSR and stakeholder theory redefines the purpose of businesses, promoting responsible, ethical, and sustainable practices that contribute to societal well-being while ensuring enduring success. This exploration serves as a call to businesses to consciously choose a path that harmonizes profitability with broader societal and environmental concerns.

Keywords

CSR, Stakeholders, Business, Conflict and Stakeholder theory

INTRODUCTION

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has emerged as a crucial facet of modern business practices, representing a shift from a singular focus on profit maximization to a broader commitment encompassing ethical, social, and environmental considerations. This paradigmatic evolution signifies a fundamental acknowledgment that businesses bear responsibilities beyond mere financial gains, extending to their impact on society and the environment. At its core, CSR encapsulates a multifaceted approach that challenges the traditional perception of businesses as solely profit-oriented entities. Instead, it urges companies to adopt a more holistic perspective, recognizing their roles as contributors to societal well-being and positive agents of change. The core principles that underpin CSR entail a commitment to ethical behavior, environmental sustainability, and active engagement with broader societal issues. The core principles of CSR are as follows:

- Ethical Responsibility:

CSR emphasizes the need for businesses to operate ethically, treating all stakeholders – employees, suppliers, and customers – with integrity and fairness. This pillar focuses on ensuring that business practices align with moral principles, avoiding exploitative behaviors and promoting honesty and transparency.

- Environmental Responsibility:

Businesses are called upon to adopt environmentally friendly practices to minimize their ecological footprint. This involves a commitment to sustainable practices, the reduction of harmful environmental impacts, and active efforts to address climate change concerns. CSR encourages companies to be stewards of the environment in which they operate.

- Philanthropic Responsibility:

CSR encompasses a commitment to actively contribute to societal well-being and make a positive impact. This pillar often involves dedicating a portion of company earnings to charitable causes or initiatives aligned with broader societal goals. It extends beyond regulatory compliance, reflecting a proactive commitment to social betterment.

- Economic Responsibility:

This principle moves beyond the traditional focus on profit maximization. It involves backing financial decisions with a commitment to doing good, aiming to positively impact the environment, people, and society. The end goal is not just profit maximization but ensuring that business operations align with broader societal goals.

The strategic importance of CSR cannot be overstated. It serves as more than a moral imperative; it is a strategic imperative that contributes to a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous future for businesses and society. Beyond mere compliance, CSR initiatives serve as powerful tools for enhancing a company’s image, positioning it favourably in the eyes of consumers, investors, and regulators. Furthermore, embracing CSR positively impacts employee engagement and satisfaction, fostering a positive and purpose-driven workplace culture. Companies that actively engage in social responsibility often attract employees who share similar convictions, creating a workforce aligned with the company’s values. CSR initiatives also provide a platform for examining and innovating in hiring and management practices, supply chain sourcing, and customer value delivery, leading to solutions that enhance both social responsibility and profitability.

In the Indian context, the trajectory of CSR has undergone significant shifts, particularly with the introduction of the 2013 Companies Act. This regulatory milestone marked a departure in how businesses approached societal concerns, steering them towards a more structured and accountable engagement with CSR. The introduction of the mandatory 2% rule under this Act underscored a commitment to creating a more inclusive and responsible business environment, making it obligatory for eligible firms to allocate a portion of their annual profits to CSR activities. CSR is a guiding principle for ethical, sustainable, and responsible business practices. Its evolution from early philanthropy to a comprehensive framework that includes environmental, ethical, philanthropic, and economic dimensions highlights its contemporary relevance. As businesses navigate an ever-evolving landscape, CSR stands out as a conscious choice to contribute to a better world while ensuring enduring success. Ultimately, CSR is about redefining the purpose of businesses, emphasizing a harmonious coexistence of profitability with societal and environmental well-being.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this article is to analyze and elucidate the intricate conflicts arising between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives and stakeholders. It aims to explore the nuanced dynamics among insiders, particularly managers with personal affiliations, and non-affiliated shareholders, especially institutional investors, shedding light on how conflicting priorities impact CSR strategies. The article seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted challenges and considerations involved in navigating these conflicts, considering factors such as ownership structures, capital considerations, and governance mechanisms within the corporate landscape.

SHAREHOLDERS

Stakeholders encompass a diverse group of individuals, entities, or organizations with a vested interest in a company’s operations and outcomes. It can be defined as “a person or group of people who own a share in a business.”[1] Shareholders, both common and preferred, constitute a crucial segment of stakeholders. As partial owners, shareholders hold stocks and benefit from the company’s success through dividends and increased stock valuations. They actively engage in decision-making processes, influencing director appointments, salaries, and constitutional changes. Moreover, shareholders wield rights such as voting on corporate matters, inspecting company records, and receiving dividends. In times of liquidation, they may claim a proportionate share of proceeds. The concept of stakeholders, therefore, extends beyond mere ownership to include a dynamic interaction between investors and the company, emphasizing both financial gains and corporate governance responsibilities.

Stakeholders actively participate in various facets of a company:

- Stakeholders, including shareholders, assert ownership rights by holding stocks, influencing decisions on director salaries, and determining powers bestowed upon directors.

- They play a crucial role in corporate governance, approving financial statements, and deciding changes in the company’s constitution.

- Shareholders exercise several rights, such as voting on corporate matters, inspecting company records, and receiving dividends from the company’s profits.

- In times of company liquidation, stakeholders, particularly shareholders, may claim a proportionate share of the proceeds.

- Stakeholders, notably shareholders, have the authority to take legal action against the corporation for the misdeeds of its directors and officers.

Collectively, these roles underscore the dynamic engagement of stakeholders in shaping the trajectory of a company, extending beyond ownership to encompass decision-making, governance, and financial impacts.

Stakeholders now play a pivotal role in corporate social responsibility (CSR), taking on a more significant role in the overall strategy of a responsible company. The foundation of a socially responsible company lies in its ‘impact culture,’ which carefully balances economic, environmental, and social concerns. CSR teams are entrusted with safeguarding this equilibrium and establishing targets for continuous impact improvement. Additionally, they are responsible for ensuring transparency and an inclusive approach towards stakeholders. The prosperity of a company is closely tied to the creation of shared added value. Acknowledging the importance of stakeholders, a company cannot thrive without their involvement in its development and evolution. This added value not only fosters collaborative innovation but also opens avenues for tailoring products and services to meet specific needs. Furthermore, it contributes to presenting a comprehensive view of the CSR strategy, emphasizing the interconnectedness of economic, environmental, and social considerations.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CSR & STAKEHOLDERS

The challenges faced by organizations in implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives underscore the need for a strategic alignment with stakeholder theory. Stakeholder Theory is a view of capitalism that stresses the interconnected relationships between a business and its customers, suppliers, employees, investors, communities and others who have a stake in the organization.[2]

Three key challenges—

- aligning business goals with employees’ goals

- maintaining clear communication about the scope of CSR

- ensuring transparency in conduct

these highlight the intricate relationships between CSR and stakeholders.

Firstly, the challenge of aligning business goals with employees’ goals requires organizations to conduct normal business operations while making their workforce aware of their responsibilities toward social and environmental concerns. Stakeholder theory plays a pivotal role in addressing this challenge by emphasizing the interconnectedness between businesses and their various stakeholders, including employees. It underscores the necessity for organizations to create value for their employees and align their goals with broader societal interests.

Secondly, maintaining clear communication about the scope of CSR is critical for successful implementation. Instances of inadequate communication between organizations and the community can lead to issues hampering CSR activities. Stakeholder theory becomes instrumental in this context by promoting a collaborative approach that considers the interests of all stakeholders. Fostering awareness and consensus-building among stakeholders, including employees, shareholders, community members, and customers, becomes essential for avoiding confusion and ensuring the effective execution of CSR initiatives.

The third challenge revolves around maintaining transparency in the conduct of CSR activities. The lack of transparency in disclosing CSR initiatives impacts trust between companies and stakeholders. Stakeholder theory addresses this issue by emphasizing the importance of accountability to all stakeholders, ensuring that their interests are considered in decision-making processes. Transparent communication becomes a critical element in building and maintaining trust, aligning with the principles of stakeholder theory.

Notably, the relationship between CSR and shareholders, who are among the most critical stakeholders in a corporation, requires careful navigation. While shareholders typically seek good returns on their investments, the emergence of socially responsible investment (SRI) funds introduces a nuanced layer. SRI funds, guided by stakeholder theory principles, consider not only financial performance but also social and environmental factors when selecting companies for investment. These funds actively engage with CSR initiatives, employing tools like ‘negative screening’ to exclude companies engaged in ethically unacceptable activities. Shareholder activism within the realm of CSR, as exercised by SRI funds, emphasizes the rights of shareholders to influence companies in alignment with social and environmental concerns. Beyond shareholders, not-for-profit organizations (NPOs) operate as stakeholders with the potential to act as restrictive factors on CSR. Despite differing aims and organizational structures, NPOs actively engage with corporations, critiquing and sometimes exposing unethical practices related to environmental pollution or poor working conditions. The examples of Royal Dutch—Shell Group and Nike illustrate the antagonistic interactions between companies and NPOs, emphasizing the significant impact NPOs can have on shaping CSR practices. The United Nations (UN) assumes a crucial role as a stakeholder in the CSR realm, particularly through initiatives like the Global Compact. The Global Compact, aligned with stakeholder theory principles, sets forth principles for human rights, labor, environment, and anti-corruption. Companies supporting these principles commit to abiding by them and reporting their activities annually to the UN. The relationship between companies signing the Global Compact and the UN exemplifies a form of resource exchange, where companies seek recognition and respect from a globally esteemed entity, aligning with stakeholder theory’s emphasis on creating value for various stakeholders.

Stakeholder theory, which emphasizes the interrelationship between a business and its various stakeholders, becomes integral in addressing the challenges of implementing CSR initiatives. This theory posits that organizations should create value for all stakeholders affected by their decisions, not solely prioritizing shareholders. The three perspectives of stakeholder theory—stakeholders impacting business operations, interconnections’ impact on key stakeholders and the organization, and key stakeholders’ viewpoints impacting the success of strategic measures—provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and addressing the challenges inherent in CSR.

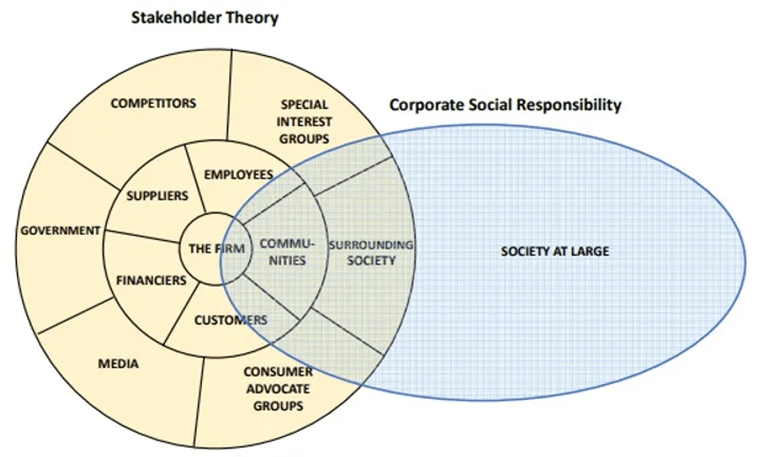

Figure 1:Interrelationship between stakeholder theory and CSR [3]

The interrelationship between stakeholder theory and CSR is illustrated in Figure 1, emphasizing the central role of stakeholders in the success of CSR initiatives. Stakeholders are critical to achieving CSR goals, and organizations must consider their impact on various stakeholders, as their decisions significantly impact stakeholders’ interests. While CSR emphasizes societal benefits, stakeholder theory works toward building relationships and value between a business and its various stakeholders. Despite differences, both concepts converge to promote responsible and ethical business practices that consider the broader interests of society. The challenges faced by organizations in implementing CSR initiatives highlight the intricate relationships between CSR and stakeholders. Aligning CSR with stakeholder theory becomes imperative for addressing these challenges strategically. Stakeholder theory provides a holistic framework that emphasizes creating value for all stakeholders, fostering awareness, consensus-building, and maintaining transparency. The interplay between CSR and stakeholders, including shareholders, NPOs, and international bodies like the UN, underscores the dynamic and multifaceted nature of responsible business practices in the contemporary global landscape.

CONFLICT BETWEEN STAKEHOLDERS DUE TO CSR

This conflict between stakeholders regarding Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) involves a nuanced examination of various factors that influence how insiders and non-affiliated shareholders perceive and prioritize CSR initiatives. One critical aspect of the conflict revolves around the diverse interests of insiders, who have a close affiliation with the company, and non-affiliated shareholders, particularly institutional investors. Insiders, including both managers and non-managers with substantial ownership stakes, may perceive private benefits from being associated with a company that has a high CSR rating. The potential conflict arises because insiders might prioritize CSR initiatives that align with their personal values or reputational considerations, even if these initiatives do not necessarily maximize overall shareholder value.

Non-affiliated shareholders, especially institutional investors, bring their own set of priorities to the table. While these stakeholders generally enhance firm value and play a monitoring role in corporate decision-making, conflicts may arise if their CSR priorities differ from those of the broader shareholder base. Institutional investors may support CSR initiatives that align with their own social or environmental criteria, even if these initiatives may reduce short-term financial returns. This highlights the complexity of balancing financial performance with social and environmental responsibilities. The conflict is not solely driven by differing priorities but is also influenced by a firm’s ownership and capital structure. High levels of insider ownership can lead to entrenchment, making it easier for insiders to promote non-value-maximizing activities, including CSR initiatives. However, beyond a certain ownership threshold, the alignment hypothesis suggests that additional insider ownership may not facilitate easier pursuit of CSR if it decreases overall firm value. This means that insiders may bear greater costs associated with expanding CSR activities, striking a delicate balance between personal affiliations and maximizing shareholder value.

The capital structure of a firm, particularly its leverage, also plays a crucial role in shaping the dynamics of the conflict. Debt servicing obligations may discourage over-investment in CSR by self-serving insiders, as creditors often have the power to influence decisions. In contrast, firms with substantial free cash flow, or excess cash available after covering obligations, may find it easier to engage in CSR activities without needing additional funds from questioning investors. The conflict is further nuanced by the interplay of corporate governance mechanisms. While CSR is often linked with good corporate governance, the conflict between insiders and non-affiliated shareholders is not strictly an agency problem but involves the reputational concerns of both groups. The presence of independent directors and the overall board composition may influence how CSR conflicts are managed within the company.

The conflict between stakeholders due to CSR is a multifaceted challenge that requires a comprehensive understanding of the motivations and priorities of insiders and non-affiliated shareholders. Navigating this conflict necessitates a delicate balance between personal affiliations, financial performance, and the social and environmental responsibilities of the company. The interplay of ownership structures, capital considerations, and governance mechanisms adds layers of complexity to this ongoing dialogue between different stakeholders in the corporate landscape.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the exploration of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its intricate relationship with stakeholders presents a vivid picture of the evolving landscape of responsible business practices. CSR, transcending profit maximization, now stands as a strategic imperative, marking a shift towards holistic commitments to ethical, social, and environmental considerations. Ethical responsibility, environmental sustainability, philanthropy, and economic responsibility form the foundation of a responsible business model, challenging traditional perceptions. Stakeholder theory emerges as a guiding framework, underscoring the essential role of stakeholders in CSR success. The dynamic interplay between businesses and stakeholders, including shareholders, non-profit organizations, and the United Nations, highlights the multifaceted nature of responsible corporate practices. Challenges in implementing CSR initiatives, such as aligning business and employees’ goals, maintaining clear communication, and ensuring transparency, underscore the strategic importance of integrating stakeholder theory. The conflict between stakeholders regarding CSR delves into the nuanced complexities of balancing personal affiliations, financial performance, and social and environmental responsibilities. This exploration unveils CSR as more than a moral obligation; it is a conscious choice businesses make to contribute to a better world while ensuring enduring success. The synthesis of CSR and stakeholder theory fosters responsible, ethical, and sustainable business practices, paving the way for a harmonious coexistence of profitability with societal and environmental well-being.

REFERENCES

- About (2024) Alt Text. Available at: http://stakeholdertheory.org/about/#:~:text=Stakeholder%20Theory%20is%20a%20view,all%20stakeholders%2C%20not%20just%20shareholders. (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

- Barnea, A. and Rubin, A. (2010) ‘Corporate Social Responsibility as a conflict between shareholders’, Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), pp. 71–86. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0496-z.

- Goankar, S. and Chetty, P. (2022) The stakeholder theory of corporate social responsibility, Knowledge Tank. Available at: https://www.projectguru.in/the-stakeholder-theory-of-corporate-social-responsibility/ (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

- Rahman, Z. (2024) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its significance in India – legal vidhiya, Legal Vidhiya . Available at: https://legalvidhiya.com/corporate-social-responsibility-csr-and-its-significance-in-india/ (Accessed: 16 January 2024).

- Team, C. (no date) ‘Shareholder’, CFI. CFI. Available at: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/equities/shareholder/ (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

- Tilt, C.A. (2016) ‘Corporate social responsibility research: the importance of context’, International Journal of corporatye r [Preprint]. Available at: https://jcsr.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40991-016-0003-7 (Accessed: 17 January 2024).

- Tokoro, N. (2007) ‘Stakeholders and corporate social responsibility (CSR): A new perspective on the structure of relationships’, Asian Business & Management, 6(2), pp. 143–162. doi:10.1057/palgrave.abm.9200218.

- Vishava (2023) ‘Shareholder’, Cleartax. Cleartax, 16 August. Available at: https://cleartax.in/glossary/shareholder/ (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

- ‘Meaning of stakeholder in English’ (no date) Cambridge University. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/stakeholder (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

[1] ‘Meaning of stakeholder in English’ (no date) Cambridge University. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/stakeholder (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

[2] About (2024) Alt Text. Available at: http://stakeholdertheory.org/about/#:~:text=Stakeholder%20Theory%20is%20a%20view,all%20stakeholders%2C%20not%20just%20shareholders. (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

[3] Goankar, S. and Chetty, P. (2022) The stakeholder theory of corporate social responsibility, Knowledge Tank. Available at: https://www.projectguru.in/the-stakeholder-theory-of-corporate-social-responsibility/ (Accessed: 18 January 2024).

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is of a personal nature.

![National Blog Writing Competition on ADR & Arbitration Law by School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University) [Cash Prizes of Rs. 15k + Internships]: Register by Aug 2](https://legalvidhiya.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/image-286-360x240.png)

0 Comments