This article is written by TANISHKA DHINGRA of University of Petroleum and Energy Studies

ABSTRACT

A happy family needs a solid marriage between the husband and wife. Islamic law views marriage as an agreement between the parties. However, there are rare instances where a husband and wife have a lot of issues upholding their married bonds, which results in a divorce. Divorce is viewed negatively in Islamic law. However, there are instances in which this evil is seen as necessary because Islam allows a couple to divorce and live apart when preserving their marriage with mutual respect and affection is difficult. The objective of this paper is to familiarise its reader with Islamic law’s guidelines for divorce. Divorce is the worst thing that has been legalized, according to the Holy Prophet (SAW). Given how bad divorce is, it should be avoided at all costs. However, there are times when this evil is necessary because it is preferable to let the parties to marriage separate rather than force them to coexist in an environment of hostility and discontent. This occurs when it is impossible for the parties to the marriage to continue their union with mutual passion and love. According to Islamic law, the incapacity of the spouses to cohabitate is what constitutes grounds for divorce rather than any particular reason (or party’s culpability). A divorce might result from either the husband’s or the wife’s actions. The law of Islam allows for different modes of divorce procedures. This paper specifically focuses on Divorce By wife viz Talaq-i-Taweez & Lian and Divorce by mutual agreement viz Khula.

KEYWORDS- DIVORCE IN ISLAM, DIVORCE BY WIFE, TALAQ, TALAQ-I-TAWEEZ, LIAN, KHULA.

INTRODUCTION

Islam, therefore, mandates that marriage must last and that the avoidance of a breach of the marriage contract. Divorce is one of the ways a marriage can be dissolved. According to Islamic law, a divorce can be granted either through the parties’ own actions or through a judicial order. However, divorce hasn’t been viewed as a general law of life, regardless of how it affects relationships. Divorce is regarded as an exception to the status of marriage in Islam.

There are three types of divorce recognized by Islamic law (Sharia), each with its own set of regulations. Talaq is the name for the divorce process that a man has started. The procedure is known as lian when a husband accuses his wife of infidelity without providing witnesses and the wife refutes the claim. Khula is the term used when a lady has started the divorce process. Talaq is easy to acquire, whereas khula is usually fairly challenging. The wife may declare divorce while exercising the right to divorce delegated by her husband. (Talaq e Tafwiz).

TALAQ- is an Arabic verbal noun derived from talaq. it means to release or untie. Technically speaking, the Muslim husband has the unilateral right to divorce his wife whenever he chooses. The word “Talaaq” is sometimes translated as “rejection,” however its Arabic roots actually mean “to release from the tether.” In legal terms, the wife’s freedom from the binding marriage denotes the husband’s unrestricted ability to divorce his wife.[1]

MODES OF DIVORCE

A husband might end their marriage simply by renunciating it without stating a cause. It is sufficient for him to pronounce the words that indicate his decision to disown his wife. Typically, talaq performs this. However, he may also be divorced by Ila and Zihar, which are only formal and not substantive

alternatives to Talaq. A wife cannot decide to end her marriage on her own. She can only get a divorce from her spouse if he gives her the authority to do so or if there is a written agreement. According to an agreement, the wife may obtain a Khul’i or Mubarat divorce from her spouse. Prior to 1939, a Muslim wife had no other grounds for divorce except false accusations of infidelity, lunacy, or the husband’s impotence. However, the dissolution of the Muslim Marriages Act of 1939 establishes a number of additional reasons on which a Muslim wife may obtain a divorce decision from the court.

The talaq divorce procedure differs for Shia and Sunni Muslims. Some Sunni schools of law hold that each time talaq is spoken, there should be a waiting period of three menstrual cycles for women or three months (iddah), during which the pair should attempt to make amends with the aid of family mediators, until the third and final talaq.

CATEGORIES OF DIVORCE UNDER ISLAMIC LAW

1. Extra Judicial Divorce

2. Judicial divorce.

Three categories of extra-judicial divorce can also be distinguished:

- Talaaq, Illa, and Zihar (by Husband).

- Lian and Talaaq-i-Taweez (by wife).

- Khula (with the consent of both parties).

CONDITIONS FOR VALID TALAQ

- CAPACITY- Any Muslim husband who is of sound mind and has reached puberty is qualified to pronounce talaq. He doesn’t have to give a justification for his statement. A husband who is young or mentally unstable cannot pronounce it. A minor or a person who is not of sound mind may not talaq, and it is invalid. However, if a husband is insane, his pronouncement of talaq during a “lucid interval” is permissible. On behalf of a minor husband, the guardian cannot utter the word talaq. When a crazy husband has no guardian, the Qadi or a judge may terminate the marriage in the husband’s best interests.

- Free Consent: The husband’s approval to declare talaq must be free consent, with the exception of Hanafi law. According to Hanafi law, a talaq that is issued under duress, coercion, undue influence, deception, or voluntary intoxication, among other circumstances, is legal and terminates the marriage.

Involuntary Intoxication: According to Hanafi law, a talaq given while under the influence of alcohol or drugs is invalid.

Shia Law: A Talaaq issued under duress, coercion, undue persuasion, deception, or voluntary intoxication is invalid and ineffectual under Shia Law (and other schools of Sunnis as well).

- Express words: The Talaaq must unequivocally state the husband’s desire to end the marriage. It is imperative to demonstrate that the husband clearly wishes to dissolve the marriage if the announcement is imprecise or confusing.

- Formalities: A Talaq may be given orally or in writing, in accordance with Sunni law. The spouse may simply say it out loud or he may write a talaq. To be considered a genuine talaq, no precise formula or term must be used. Any gesture that makes it evident that the husband wants to divorce the wife is adequate. It is not required to be made in front of the witnesses. Shias believe that Talaaq must be spoken aloud, with the exception of situations where the husband is mute. The talaq is null and void in accordance with Shia law if the husband can talk but offers it in writing. Here, the talaq must be administered in front of two witnesses.

TALAQ-i-TAWEEZ

Both Shias and Sunnis accept talaaq-it-taweez, also known as delegated divorce. The Muslim spouse can give his wife or anybody else the authority to declare divorce. Although the husband has the primary authority to grant a divorce, he can delegate that authority to the wife or to a third party, unconditionally or on the condition that they meet certain conditions, either temporarily or permanently. The divorce may thereafter be declared by the person to whom the power has been thusly transferred A temporary delegation of power cannot be revoked, whereas a permanent delegation of power can. The power must be explicitly granted to the person it is being delegated to, and the delegation’s goal must be clearly made. In India, a Muslim wife may divorce her husband using the authority that her husband has assigned to her if he marries a second woman under certain circumstances.[2] If a Muslim wife learns that her husband has taken a second wife, she does not forfeit her right to exercise the right to divorce herself provided to her by the marriage contract, as the second marriage is not a one-time wrong but rather a continuing one to the first wife.[3]

Usually, prenuptial agreements contain provisions for this kind of delegated divorce. Even in agreements established after a marriage, the right to divorce may be delegated. Therefore, where it is stipulated in a contract that she would have the right to declare divorce on herself in the event that the husband does not provide for her support or marries a second woman, such a contract is legitimate and such terms are reasonable and do not go against public policy. It should be highlighted that even in the case of a contingency, the wife will decide whether or not to use her power; she may decide to do so or not. Divorce does not necessarily follow the occurrence of the contingency event.

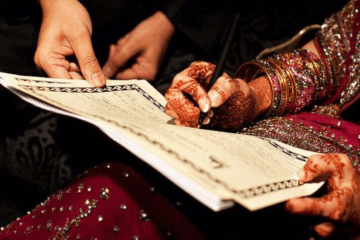

Even though both spouses signatures appear on the Kabinnama in the current instance, the groom insisted that his wife be able to provide talaq ex parte at her discretion in his own will. A clause like that cannot be viewed as a bilateral delegation of the right to offer talaq, even though it is part of a document that both spouses have signed. Therefore, the husband had unilaterally granted the wife the right to an unconditional divorce, and as this is not against the parties’ personal law, she was free to do so whenever she pleased. It cannot be stated that the marriage was still in existence because no stipulated events had occurred when the wife dissolved her marriage using the authority entrusted to her and signed a divorce deed before the Muslim Marriage Registrar and Kazi.[4]

Stipulation by wife for the right of divorce.

A prenuptial or postnuptial agreement that stipulates that the woman shall be free to file for divorce under certain circumstances is acceptable as long as the terms are reasonable and do not conflict with Mahomedan law’s general policy. When such an agreement is signed, the wife has the right to renounce it at any point after the occurrence of any of the events, and the divorce will then be effective to the same extent as if the husband had issued a talaq.[5] The wife may exercise the authority that has been given to her in this manner even after an action has been filed against her for the restoration of conjugal rights.[6]

At any time After the happening of contingency,

If a wife’s right to divorce herself upon her husband remarrying is granted under the marriage contract, she is not required to exercise that right as soon as she learns that her husband has wed another. She has ongoing rights to use the power because of the ongoing wrong that has been done to her.[7]The marriage does not end just because the circumstance that would allow the wife to exercise her right occurs. She needs to use authority.[8]

LIAN

A woman who has been married under Islamic law is eligible for a divorce on any other ground[9] recognized by Islamic law.[10] Therefore, the wife would be allowed to file for divorce if the husband called Lian made a false, hostile, and voluntary accusation of adultery[11]. According to Muslim law, a wife who has reached the majority can bring a lawsuit by herself without a guardian.[12] The accusation must be untrue and false.[13]

The woman must file a formal lawsuit rather than a simple application in order to petition for divorce on this ground because a simple charge or accusation will not end the marriage. The marriage continues up until a divorce decree is issued by the court.[14]

The wife cannot file for divorce on this ground if the charge is legitimately withdrawn before the hearing begins, but she cannot do so if the withdrawal occurs after the conclusion of the trial or the closing of the evidence.[15] In these cases, the withdrawal is not legitimate.

Therefore, there are three requirements that must be met for a retraction to be considered valid: (1) the husband must acknowledge that he falsely accused the wife of adultery; (2) the husband must acknowledge that the accusation was false; and (3) the husband must make the retraction before the trial is over.[16]

There are three prerequisites for Lian:

• The couple’s marriage should still be in an active state.

• The marriage agreement must be legitimate. Mula’ana is not used, for instance, if there were no witnesses to the couple’s marriage.

• The husband must be liable to testify and not be subject to the qazf (false accusation) penalty.[17]

KHULA

A marriage can be ended by consent between the husband and wife as well as by the husband’s arbitrary act, or talaq. A divorce that has been agreed upon may be accomplished through khula or mubarat. A divorce by khula is one in which the wife initiates it and gives or agrees to give the husband something of value in exchange for being freed from the marriage’s ties. The details of the agreement are matters of arrangement between the husband and wife in such a situation, and the wife may, as a consideration, waive her dyn-mahr (dower) and other rights or enter into any other agreement for the husband’s advantage. A khula divorce is initiated by the husband accepting the wife’s offer to pay the husband in exchange for releasing her from her marital obligations.

When an offer is accepted, it becomes a single irrevocable divorce (talak-i-bain), and its effects are not delayed until the khulanama (deed of khula) is carried out.[18] The dissolution of a marriage by mutual consent is the same as a khula divorce, however, the origin of the two is different.

The transaction is known as khula when the wife has an aversion and wants to separate from her husband. The transaction is known as mubara’at when there is mutual distaste and a desire for separation on both sides. Khula is a mutually agreeable divorce where the wife promises to take her husband’s wishes into consideration. It is essentially a “redemption” of the marriage contract. Literally, the word khula, or redemption, means to lie down. In legal terms, it refers to a husband giving up his power and right over his wife.

Their Lordships of the Judicial Committee provided an accurate definition of khula in Moonshee-Buzlu-ul-Raheem v. Lateefutoonissa. A divorce by khula is one where the wife initiates it and gives or agrees to give the husband anything of value in exchange for her release from the marriage contract. It refers to a deal reached to end a romantic or sexual relationship instead of the wife paying the husband money from her assets as compensation. Khula talaq is actually a divorce right that the wife has acquired from her husband.

ESSENTIALS OF KHULA

The wife must make an offer, which the husband must accept in exchange for his freedom,

Consideration:

Everyone is in agreement that consideration can include anything and everything that can be presented as a dower. There are situations where the wife consents to pay anything in exchange for being released but breaks her word once her husband divorces her. As soon as the offer for khula is accepted, it becomes an irrevocable divorce, and the wife is required to observe iddat, therefore in this situation, the divorce remains lawful and the husband is still entitled to the consideration.

CAPACITY

In accordance with Shia law, the husband must be an adult, of sound mind, a free agent, and have the purpose to divorce her. These requirements are also necessary for the performance of khula. Only two requirements must be met according to Sunni law, namely that the spouse be an adult and of sound mind.

It was stated in Mst. Bilquis Ikram v. Najmal Ikram that under Muslim Personal Law, the wife is entitled to Khula as of right if she satisfies the court’s conscience that refusing to do so would require pushing her into an unfavorable relationship.

What is the difference between Khula and Mubarat?

In Islam, there are two distinct types of divorce: khula and mubarat.

The wife initiates khula talaq, in which she requests a divorce from her husband by paying back the dower (mahr) or renouncing some of her rights. Before issuing the divorce, the husband may accept or reject the request, and the court may also make an effort to patch up the relationship. In the Khula divorce procedure, the wife formally requests to end the marriage on legal grounds, such as incompatibility or cruelty, and is prepared to give up part of her rights or pay a fee in exchange.

On the contrary, mubarat is started by the consent of both the husband and the wife, whereby they both agree to dissolve the marriage without citing any cause or fault. Mubarat is a process that can be started by any partner, and both parties must agree to dissolve the marriage. This is in contrast to Khula, where the wife initiates.

Khula is a type of divorce that is started by the wife, who desires to end the marriage on legal grounds and is prepared to give up some of her rights in order to do so. This is the fundamental distinction between Khula and Mubarat. On the other side, mubarat is a type of divorce that both the husband and wife initiate with mutual consent and without giving a cause.

CONCLUSION

In the case of Md. Khan v. Shahmai, a Khana Damad husband agreed, as part of a prenuptial agreement, to reimburse the father-in-law for certain marriage-related expenses in the event that he left the home and gave his wife the authority to obtain a divorce. The spouse refused to pay the money and left his father-in-law’s home. The wife made use of her right and filed for divorce. In using the authority granted to her, it was determined that the divorce was legal. Even in post-marriage arrangements, power might be delegated. Therefore, where it is stipulated in an agreement that she will have the right to declare divorce on herself in the event that the husband does not pay her maintenance or marries another woman, such an agreement is legitimate and such conditions are reasonable and do not go against public policy. It should be highlighted that even in the event of a scenario, the woman has the discretion to decide whether or not the power would be used. Divorce is not always the result of a contingency event occurring.

Through the judicial interpretation of specific Muslim law rules, the concept of divorce based on the irretrievable collapse of a marriage has emerged in Muslim law. It was stated in the 1945 case of Umar Bibi v. Md. Din that the wife’s hatred of her husband was so great that she could not possibly coexist with him and that their temperaments were completely incompatible.

The court declined to issue a divorce decree on these reasons. But in Neorbibi v. Pir Bux, a case from 25 years later, a new attempt was made to award a divorce on the grounds of irretrievable dissolution of the marriage. This time, the divorce was approved by the court. There are so two grounds for divorce under contemporary Indian Muslim law: Instances of (a) the husband failing to pay maintenance even though it was caused by the wife’s actions and (b) complete irreconcilability between the couples.

The divorced wife often retains her mahr, including the initial gift and any supplemental property included in the marriage contract, if her husband requests a divorce. Additionally, she receives child support up until the child is weaned, after which the couple or the courts will decide who will have custody of the child. While women encounter several financial and legal challenges when divorcing their partners, males can do it with ease. However, those advocating more liberal interpretations of Islam are putting more and more pressure on this divisive area of religious practise and history.

[1] Lawal Mohammed Bani, Hamza A. Pate, Dissolution of Marriage (Divorce) under Islamic Law, Vol.42, Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization,138 (2015), available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234650383.pdf

[2] Badu Mia v Badranessa AIR 1919 Cal 51; Sheikh Mohammad v Badrunissa Bibee 7 Beng LR App 5; Badarannissa Bibi v Mafiattala 7 Beng LR 442.

[3] Ayatunnissa Beebee v Karam Ali ILR 36 Cal 23.

[4] Mangila Bibi v Noor Hussain, AIR 1992 Cal 92

[5] Hamidoola v Faizunnissa, (1882) 8 Cal 327; Ayatunnessa Beebe v Karam Ali, (1909) 36 Cal 23; Maharam Ali v Ayesa Khatun, (1915) 199 Cal WN 1226: 31 IC 562; Sainuddin v Latifannessa Bibi, (1919) 46 Cal 141: 48 IC 609: AIR 1919 Cal 631 (agreement after marriage).

[6] Sainuddin v Latifannessa Bibi, (1919) 46 Cal 141: 48 IC 609

[7] Ayatutmessa Bebbe v Karam Ali, (1909) 36 Cal 25: 1 IC 513.

[8] Aziz v Mst. Nam, AIR 1955 HP32

[9] Bibi Rehana v Iqtidarruddin AIR 1943 All 295.

[10] Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act 1939 s 2(ix).

[11] Nurjahan v Kajim Ali AIR 1977 Cal 90

[12] Ahmed v Bai Fatima AIR 1931 Bom 76

[13] Zafar Hussain v Ummat-ur Rehman (1919) ILR 41 All 278

[14] Khatijabi v Umar Sahib AIR 1928 Bom 285

[15] Siju Bibi v Muksed Mollah 45 Cal WN 122; Tufail Ahmed v Jamila Khatun AIR 1962 All 570

[16] Tufail Ahmed v Jamila Khatoon AIR 1955 Bom 464.

[17] Supra 1, available on page no. 142.

[18] Monshee Buzul-ul-Raheem v Luteefutoon-Nissa, (1861)

0 Comments