This article is written by Mehak Vardhan of BBA LLB of NMIMS Kirti P. Mehta School of Law, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

Abstract:

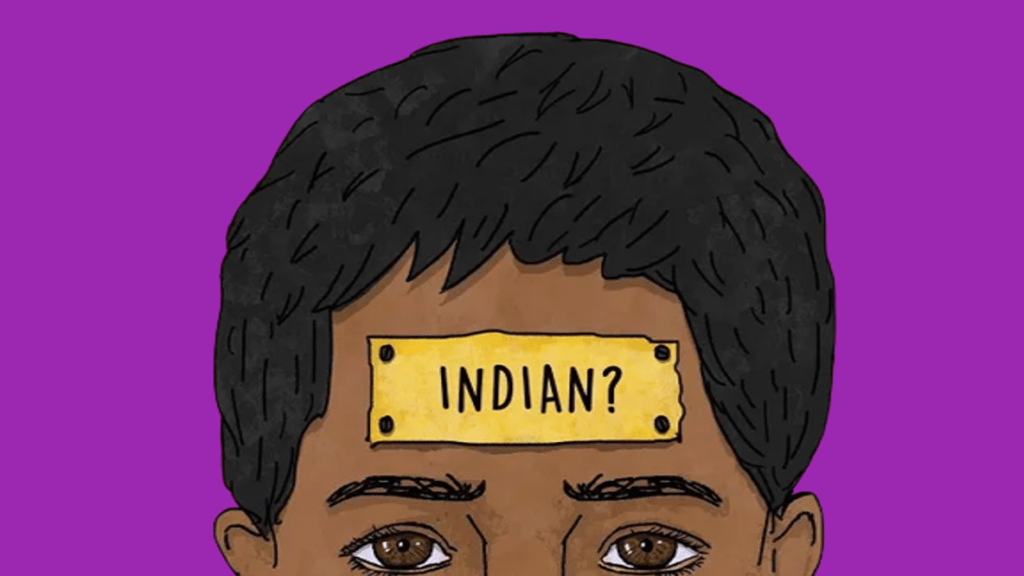

The Citizenship Act of 1955, a foundational piece of Indian legislation, governs the processes of acquiring, losing, and forfeiting citizenship in India. This comprehensive analysis explores the Act’s historical development, its objectives, the methods for acquiring and losing Indian citizenship, and its relationship with the Indian Constitution. Over the years, the Act has undergone multiple amendments, significantly influencing the criteria for obtaining Indian citizenship. It introduced concepts like birthright and blood relationship, addressed dual citizenship, and included provisions relevant to government employees. Notably, the contentious 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act sought to confer Indian citizenship on specific religious minority groups, leading to significant debates. Furthermore, the Act acknowledges categories such as Overseas Citizens of India (OCI), Non-Resident Indians (NRI), and Persons of Indian Origin (PIO), providing avenues for engagement with the Indian diaspora. Although OCIs enjoy certain rights, they differ from full Indian citizens and have the option to renounce their status. The Act emphasizes the finality of citizenship decisions, making them unchallengeable in a court of law, which helps maintain legal clarity. The Act’s framework is firmly rooted in the constitutional provisions delineated in Articles 5 to 11 of the Indian Constitution, which define the scope and regulation of citizenship within the country.

Keywords– Citizenship Act 1955, Indian citizenship, Constitution of India, Citizenship acquisition and termination, Overseas Citizens of India (OCI), Assam Accord

Introduction

The Citizenship Act of 1955, commonly referred to as the Indian Nationality Law, holds significant importance as a key piece of legislation that delineates the association between individuals and the nation of India. This Act is the principal authority determining the eligibility criteria for Indian citizenship, setting forth the privileges, obligations, and commitments associated with it. It was passed by the Indian Parliament on December 30, 1955, and stands as a foundational legal framework that defines the boundaries of Indian citizenship, with a central role in safeguarding the well-being and liberties of Indian citizens.

Definition

The Citizenship Act of 1955 delineates the processes for acquiring or relinquishing citizenship post the commencement of the Constitution. Initially, this legislation encompassed clauses related to Commonwealth Citizenship, but they were subsequently removed by the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2003.

Evolution of Indian Citizenship Act

The concept of Indian citizenship came into existence following India’s independence in 1947. Prior to that, during the British colonial era, Indians were not granted distinct citizenship rights and were instead classified as British subjects. This status was governed by the British Nationality Act of 1914 until it was revoked in 1948. The partition of India in 1947 resulted in significant population movements between India and Pakistan, necessitating the establishment of a framework for determining citizenship. Initially, the Constituent Assembly addressed this matter to facilitate the citizenship of migrants. Subsequently, in 1955, the Indian Parliament passed the Citizenship Act, which established specific provisions and eligibility criteria for Indian citizenship.

Statement of Objective

The Indian Citizenship Bill of 1955 delineates the regulations governing the acquisition and cessation of citizenship in India. This legislation encompasses the criteria for citizenship by birth, descent, registration, naturalization, and the incorporation of territory. Additionally, it outlines the procedures for the forfeiture and deprivation of citizenship in certain situations. It is worth noting that this bill formally acknowledges Commonwealth citizenship and empowers the Central Government to confer reciprocal rights, as agreed with other Commonwealth nations and the Republic of Ireland, upon Indian citizens. The explanatory notes accompanying the clauses provide additional insights into the key provisions of the Bill.

Renunciation of citizenship

Individuals can renounce their citizenship in India through several avenues:

- Voluntary Renunciation: Should an adult Indian citizen choose to do so, they can formally renounce their Indian citizenship through an official declaration. In such cases, the children of the individual also lose Indian citizenship, but they retain the option to reclaim it upon reaching the age of 18.

- By Termination: According to the Indian Constitution, an individual is allowed citizenship in only one country at a time. Acquiring citizenship in another nation automatically terminates their Indian citizenship, except in times of war.

- Deprivation by Government: The Indian government possesses the authority to revoke an individual’s citizenship under specific circumstances, including:

- Disrespecting the Constitution.

- Obtaining citizenship through fraudulent means.

- Unlawfully engaging in trade or communication with the enemy during wartime.

- Receiving a two-year imprisonment sentence in any country within five years of registration or naturalization.

- Continuous residence outside India for seven years.[1]

Deprivation of citizenship

Deprivation of citizenship involves the compelled termination of an individual’s Indian citizenship, a measure enforced by the Central government under specific circumstances. It is crucial to recognize that not all citizens are susceptible to this provision. Citizenship can be mandatory terminated if:

- The individual acquired citizenship through fraudulent means.

- The individual demonstrated disloyalty to the Indian Constitution.

- The individual engaged in prohibited trade or communication with the enemy during a war.

- Within five years after registration or naturalization, the individual received a two-year imprisonment sentence in any country.[2]

Provisions of this act

- Ways to Attain Indian Citizenship

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1955 offers several pathways for individuals to attain Indian citizenship, catering to diverse circumstances. These avenues encompass:

- Citizenship by Birth: Individuals born within the geographical boundaries of India automatically qualify for Indian citizenship.

- Citizenship by Descent: Applicable to individuals born outside India, provided that their parents are Indian citizens.

- Citizenship by Registration: Individuals with Indian lineage can apply for citizenship through this method.

- Citizenship by Naturalization: Those who have resided in India for an extended duration can pursue citizenship through the naturalization process.

- Citizenship by Incorporation of Territory: In cases where the Indian government integrates a new territory, the inhabitants of that region become eligible for Indian citizenship.

- Citizenship under the Assam Accord: Special provisions exist for individuals associated with the Assam Accord, facilitating their acquisition of citizenship.

These diverse provisions accommodate individuals with varying backgrounds and connections to India, enabling them to rightfully obtain Indian citizenship.

2. Termination of Indian Citizenship

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1955 specifies conditions under which one’s Indian citizenship may be terminated. These include:

- Renunciation of Citizenship: If an individual willingly renounces their Indian citizenship, it is legally revoked.

- Acceptance of Another Citizenship: Indian citizens who voluntarily accept the citizenship of another country may have their Indian citizenship terminated.

- Deprivation of Citizenship: The government of India can directly revoke citizenship, particularly for those who acquired it through naturalization, registration, or Article 5. This may occur in cases where:

a) An individual engages in acts or speech that are disrespectful or contrary to the interests of the nation.

b) Deceptive practices are used to obtain Indian citizenship.

c) Involvement in anti-national activities, such as sharing national secrets with the nation’s enemies during wartime.

d) A citizen residing outside India for over seven years without returning, except for educational or official reasons.

These provisions ensure that Indian citizenship is upheld with respect to national interests and the actions of its citizens

3. Commonwealth Citizenship and Rights

According to the Indian Citizenship Act, individuals who hold citizenship in Commonwealth countries as listed in the First Schedule are recognized as Commonwealth citizens in India. Moreover, the Central Government possesses the authority, contingent on reciprocal agreements, to bestow some or all of the privileges associated with Indian citizenship to citizens hailing from countries mentioned in the First Schedule. These granted privileges retain their legal validity, even if they potentially conflict with other laws, except for the Constitution of India or the Citizenship Act itself. It’s crucial to emphasize that the rights conferred to a citizen from a Commonwealth country in India are determined by the Central Government through agreements, and they may not encompass all the entitlements of full Indian citizenship. A noteworthy precedent in this regard is the case of Fazal Dad v. State of Madhya Pradesh (AIR 1964 MP 272), which established that a citizen of a Commonwealth country can only possess the rights that the Central Government chooses to bestow.

4. Certificate of Citizenship in Case of Doubt

When there is uncertainty about an individual’s Indian citizenship, the Central Government has the authority to issue a certificate confirming that the person is, indeed, a citizen of India. This certificate is considered conclusive evidence of the person’s citizenship on the date it is issued. However, if it can be proven that the certificate was obtained through fraudulent means, false representation, or concealing essential information, its validity can be challenged.

Importantly, this certificate does not prevent the person from providing evidence of their citizenship from an earlier date, should such a need arise. This provision helps resolve doubts about an individual’s citizenship in a legal and documented manner.

5. Disposal of Citizenship Applications

According to this section, the designated authority or the Central Government holds the discretion to either accept or deny applications submitted under Section 5 or Section 6 of the Citizenship Act. They are not compelled to furnish justifications for their determinations. Significantly, once a decision is rendered, it is regarded as ultimate and immune to legal contestation in court. This clause guarantees that the authority’s verdict on citizenship applications is definitive and beyond the scope of legal challenges.

6. Revision of Citizenship Orders

If an individual is unsatisfied with an order issued under the Citizenship Act by the authorized body or any official or entity (except the Central Government), they have the opportunity to request a review of that order by applying to the Central Government. This application must be submitted within thirty days from the date of the initial order, although the Central Government may entertain applications filed after this timeframe if there is a legitimate justification for the delay. After receiving the application, the Central Government will conduct an evaluation, considering the inputs of the affected person and any reports furnished by the officer or entity responsible for the original order. Subsequently, the Central Government will issue a conclusive decision regarding the application, which cannot be subject to further legal challenges. This provision enables individuals to seek a reassessment of orders related to citizenship matters.

7. Offences Under the Act

According to the Citizenship Act, individuals who intentionally provide incorrect information to either obtain or obstruct actions mandated by this legislation may be subject to legal repercussions. Such consequences may involve imprisonment for a maximum of six months, a monetary fine, or a combination of both. In summary, the act of knowingly making false statements in affairs associated with the Citizenship Act can result in legal actions being taken against the individual.

8. Amendments to the Citizenship Act

The Citizenship Act of 1955 has undergone several amendments over the years. These amendments have refined the criteria for acquiring Indian citizenship.

- The 1986 amendment introduced restrictions on birthright citizenship, conferring citizenship to those born in India only if certain conditions were met.

- The 2003 amendment made these conditions even more stringent, particularly concerning the status of one’s parents. It leaned towards the principle of jus sanguinis, where citizenship is determined by blood relationship.

- In 2005, a dual citizenship system was introduced, allowing citizens of many countries to hold Indian citizenship, with exceptions for Pakistan and Bangladesh.

- The 2015 amendment made provisions for government employees and streamlined the Overseas Citizens of India and Persons of Indian Origin schemes.

- The 2019 amendment, the Citizenship Amendment Act, focused on granting Indian citizenship to specific religious minority groups from neighbouring countries. It aimed to reduce the naturalization period for certain communities and protect them from legal actions related to their entry into India. However, this amendment also sparked controversy and protests in some regions.

9. Overseas Citizens and Non-Resident Indians (2003 Amendment)

The distinction between Overseas Citizens of India (OCI) and Non-Resident Indians (NRI) holds significant importance in comprehending the Indian diaspora. An OCI is an individual of Indian origin who holds citizenship in a specific foreign country or has previously been an Indian citizen and received OCI status from the Indian government. Conversely, NRIs are Indian citizens who temporarily reside in other nations, typically for purposes such as employment or education, while retaining their Indian citizenship and passports. Furthermore, Persons of Indian Origin (PIO) are individuals with ancestral ties to India but are citizens of foreign countries. These categorizations acknowledge and facilitate the relationships and contributions of the global Indian diaspora, underscoring citizenship as a fundamental component of India’s democratic principles.

10. Rights and Renunciation of Overseas Citizenship

The Citizenship Act of 1955 contains provisions regarding Overseas Citizens of India (OCI). These provisions afford certain privileges to OCIs, but they are not on par with the rights of Indian citizens. For instance, they are restricted from seeking specific government positions, participating in elections, or serving as judges. The Act also stipulates the procedure for renouncing OCI status, whereby following a prescribed process leads to the cessation of OCI status. Additionally, the Act authorizes the Central Government to revoke an OCI’s registration in cases involving fraudulent acquisition, engagement in activities against India’s interests, violation of laws, or posing a threat to the nation’s sovereignty and integrity. The Act addresses situations such as dissolution of an OCI’s marriage or entering into another marriage without dissolving the previous one. Importantly, the cancellation of registration can only transpire after affording the individual a fair opportunity to present their case.

Citizenship and the Indian Constitution

In India, citizenship is addressed in Articles 5 to 11 of the Indian Constitution, which fall under Part 2. These articles cover various aspects of citizenship:

- Article 5: This article establishes the concept of citizenship right at the beginning of the Constitution.

- Article 6: It deals with the citizenship rights of individuals who migrated to India from Pakistan.

- Article 7: Focuses on the citizenship rights of certain Pakistani migrants in India.

- Article 8: Describes the citizenship rights of individuals of Indian origin living outside India.

- Article 9: States that a person who willingly acquires the citizenship of a foreign country is no longer considered an Indian citizen.

- Article 10: Addresses the continuity of citizenship rights for existing citizens.

- Article 11: Outlines how Parliament has the authority to regulate citizenship rights through legislation. These constitutional provisions help define the parameters of Indian citizenship and its regulation.

Challenges Against Section 6A of Citizenship Act, 1955

A Constitution Bench, presided over by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud, is set to commence hearings on October 17 for a series of petitions that challenge the constitutionality of Section 6A within the Citizenship Act of 1955. Section 6A was incorporated as part of the ‘Assam Accord’ in 1985 with the aim of protecting and upholding the cultural, linguistic, and social identity of Assam. The Accord was the result of a six-year-long movement led by the All-Assam Students Union to detect and repatriate illegal immigrants, primarily from neighbouring Bangladesh.

- Background of Section 6A

Section 6A of the Citizenship Act of 1955 deals with individuals from foreign countries who came to Assam before January 1, 1966, and were considered “ordinarily resident” in the state. It provided them with the privileges and responsibilities of Indian citizens. Those who arrived in Assam between January 1, 1966, and March 25, 1971, would also enjoy the same rights and obligations, except for a 10-year restriction on their voting rights.

2. Challenges to Section 6A

Numerous legal challenges have been initiated to contest the perceived discriminatory aspects of Section 6A concerning the conferment of citizenship to immigrants, particularly those who are considered to have entered the country unlawfully. The petitioners, among them Assam Public Works and others, contend that this unique provision is in conflict with Article 6 of the Indian Constitution, which establishes the specific date, July 19, 1948, as the cutoff point for granting citizenship to immigrants.

3. The Case and Questions Raised

In December 2014, the Supreme Court articulated 13 specific questions designed to tackle the constitutional aspects of Section 6A. These queries encompassed a range of issues, such as whether the provision diminished the political rights of individuals in Assam, if it contravened the rights of the Assamese populace to safeguard their cultural identity, and whether the inflow of illegal migrants into India could be considered as “external aggression” and “internal disturbance,” among other pertinent matters. Subsequently, in 2015, a three-judge Bench of the court decided to transfer the case to a Constitution Bench.

4. Relevance of Recent Developments

- For an extended period, the case related to Section 6A remained unresolved, coinciding with the Supreme Court’s oversight of the final Assam National Register of Citizens (NRC) list’s creation and release in August 2019. This NRC list resulted in the exclusion of more than 19 lakh individuals. Additionally, the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which facilitated expedited citizenship for immigrants belonging to minority communities in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, was enacted.

- This case holds paramount significance as it questions the validity of a provision central to the Assam Accord and carries broader implications for how immigrants are treated in India, particularly within the state of Assam. The legal proceedings will thoroughly assess whether Section 6A aligns with the provisions and principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

Relevant Case Laws:

• Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India (2005): In this legal precedent, commonly referred to as the “Assam Illegal Migrants” case, the focus was on addressing the challenge of illegal immigration in Assam. The Supreme Court underscored the crucial need to identify and deport illegal immigrants to protect the rights and interests of Indian citizens. This case resulted in the creation of Foreigners Tribunals and subsequent amendments to the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam.

• Mohammed Shakeel v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2008): In this case, the Supreme Court clarified the distinction between nationality and citizenship. It emphasized that being granted Indian nationality does not automatically confer Indian citizenship, highlighting the existence of a separate legal process for acquiring Indian citizenship outlined in the Citizenship Act.

• National Legal Services Authority v. Union of India (2014): This landmark case acknowledged and upheld the rights of transgender individuals, specifically recognizing their right to self-identify their gender. It emphasized that transgender persons are entitled to all the rights and privileges available to any other Indian citizen, including the right to citizenship.

• Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018): In this groundbreaking case, the Supreme Court decriminalized consensual same-sex relationships in India by invalidating Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. The judgment acknowledged the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals, affirming their entitlement to dignity, privacy, and equal citizenship.[3]

Conclusion:

The Citizenship Act of 1955 holds immense significance within the legal framework of India as it defines the parameters of Indian citizenship, delineating who can be recognized as an Indian citizen and the associated rights and responsibilities. Its evolution, spanning from the pre-independence period to subsequent amendments, has meticulously shaped the criteria for acquiring citizenship in India. This legislation plays a pivotal role in addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by the Indian diaspora and distinguishes between OCI, NRI, and PIO statuses. Furthermore, the intricate relationship between this Act and the Indian Constitution clarifies the legal boundaries of Indian citizenship. While the Act provides a structured framework for citizenship acquisition and termination, it has not been without its share of controversies, as exemplified by the 2019 Amendment. This critical analysis sheds light on the complex network of laws and principles that revolve around Indian citizenship, encompassing legal, social, and political implications. It serves as a foundation for ongoing dialogues and potential future amendments in response to the ever-evolving societal and global dynamics.

References

- https://unacademy.com/content/clat/study-material/legal-reasoning/citizenship-act-1955/#:~:text=Conclusion%3A,the%20basic%20rights%20they%20need.

- https://indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/uploads/directorate/security/rpf/Files/law/BareActs/Citizenshipact.doc#:~:text=This%20Bill%20provides%20for%20the,of%20citizenship%20under%20certain%20circumstances.

- https://www.drishtiias.com/loksabha-rajyasabha-discussions/75-years-laws-that-shaped-india-the-citizenship-act-1955#:~:text=The%20Citizenship%20Act%2C%201955%20provides,(Amendment)%20Act%2C%202003.

- https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/citizenship-1434782934-1

- https://indiancitizenshiponline.nic.in/UserGuide/Citizenship_Act_1955_16042019.pdf

- https://prepp.in/news/e-492-citizenship-act-1955-indian-polity-notes

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_nationality_law

- https://www.livelaw.in/columns/which-documents-prove-indian-citizenship-153027

- https://www.npr.org/2019/05/10/721188838/millions-in-india-face-uncertain-future-after-being-left-off-citizenship-list

- https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1540405608208/1568898474141

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/renunciation-of-indian-citizenship-1#:~:text=If%20an%20Indian%20citizen%20wishes,he%20may%20resume%20Indian%20citizenship.

- https://prepp.in/news/e-492-loss-of-citizenship-indian-polity-notes

- https://blog.finology.in/Legal-news/citizenship-act-of-india#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Citizenship%20Act,but%20before%20July%201st%2C%201987

- https://www.studyiq.com/articles/citizenship/

- https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/indian-citizenship

- https://projectupsc.wordpress.com/2017/09/09/citizenship/

[1] Renunciation of Indian Citizenship. (n.d.). Drishti IAS. https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/renunciation-of-indian-citizenship-1#:~:text=If%20an%20Indian%20citizen%20wishes,he%20may%20resume%20Indian%20citizenship.

[2] Patil, A. (n.d.). Loss of Citizenship – Indian Polity Notes. Prepp. https://prepp.in/news/e-492-loss-of-citizenship-indian-polity-notes

[3] Citizenship Act of India: Meaning, Controversies and Cases. (n.d.). Finology. https://blog.finology.in/Legal-news/citizenship-act-of-india#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Citizenship%20Act,but%20before%20July%201st%2C%201987.

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is of a personal nature.

![National Blog Writing Competition on ADR & Arbitration Law by School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University) [Cash Prizes of Rs. 15k + Internships]: Register by Aug 2](https://legalvidhiya.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/image-286-360x240.png)

0 Comments