This article is written by Samiksha Jadhav of University of Mumbai Law Academy, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

Abstract

The idea of open prisons signifies a transformative change in the approach to punishment from retributive to reformative justice. Based on the ideals of trust, rehabilitation, and reintegration, open prisons provide a more flexible setting where inmates experience increased personal liberty, frequently participate in meaningful work, and are systematically readied to return to society as accountable individuals. In contrast to traditional prisons, these facilities function with limited oversight, allowing inmates to live with respect, uphold family connections, and reconstruct their lives. By examining significant court rulings and empirical evidence, especially from regions like Rajasthan that have successfully adopted this model, the research investigates if open prisons can be expanded nationally to tackle urgent problems like overcrowding, elevated maintenance expenses, and the inability of conventional imprisonment to lower recidivism rates. The article provides comparative insights from global practices to situate the Indian approach within worldwide penal reform efforts. This research argues that although open prisons present significant promise as an alternative correctional approach, their effectiveness relies on solid policy backing, strong infrastructure, and a change in societal and institutional views on rehabilitation. The article wraps up by presenting actionable suggestions for broadening the open prison model in India, thus bringing the criminal justice system in line with constitutional principles of human dignity, freedom, and social justice.

Keywords

Open prisons, penal reform, rehabilitation, criminal justice system, prison overcrowding, reformation, custodial freedom, parole, India.

Introduction

The criminal justice system in any nation aims not just to penalize offenders but also to rehabilitate and reintegrate them into society. Conventional prisons have often faced criticism due to their punitive approach, severe conditions, and ineffectiveness in rehabilitating offenders. Overpopulated institutions, inadequate living environments, insufficient mental health assistance, and restricted availability of skill-building programs have sparked significant worries about the human rights of inmates. Conversely, the idea of open prisons—or minimum-security facilities—presents a different, rehabilitative approach that emphasizes trust, accountability, and reintegration rather than confinement and seclusion.

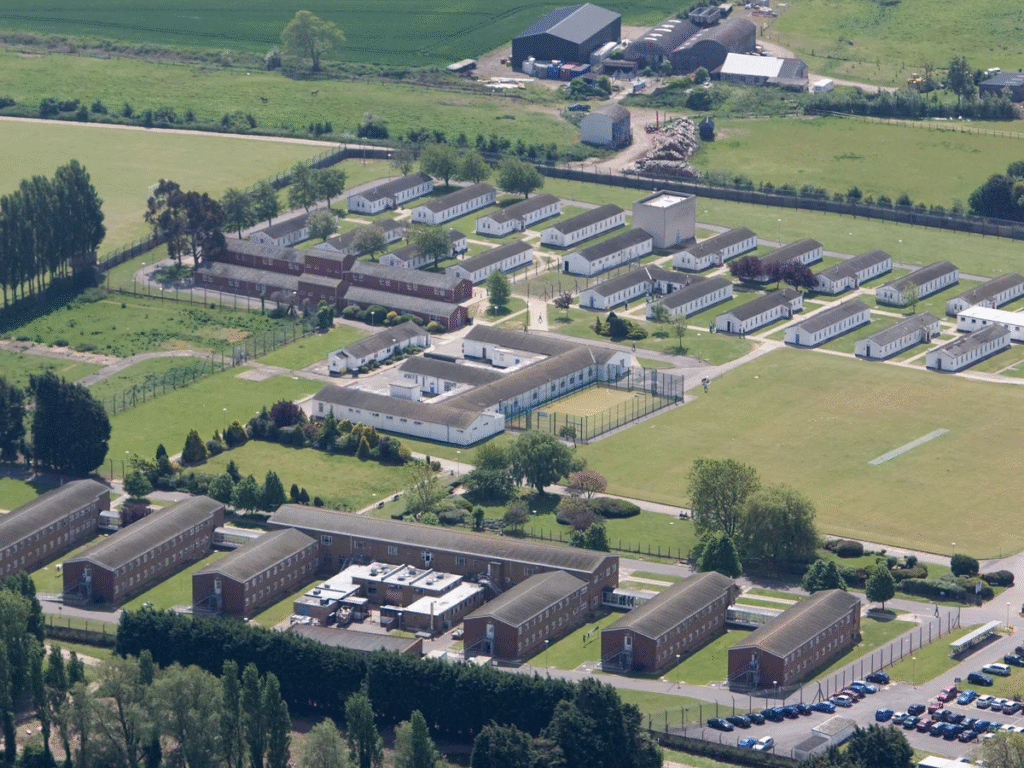

Open prisons are correctional facilities that permit certain inmates—usually those displaying good conduct and close to completing their sentences—to reside and work in less restrictive settings, often beyond the prison confines. These facilities operate on the concept of minimal oversight, permitting inmates to work, keep familial connections, and help the community, all during their incarceration. Originally launched in India in the early 20th century, the open prison model has gradually gained popularity, with states such as Rajasthan showcasing its success on a significant scale.

This research paper aims to examine the feasibility of open prisons as a key element of India’s prison reform initiative. It starts by outlining the historical evolution and legal acknowledgment of open prisons in India and other countries. It subsequently explores the advantages these institutions provide—like alleviating overcrowding, cutting prison expenses, and promoting inmate rehabilitation—while also tackling the major obstacles they encounter, such as public distrust, safety issues, and uneven policy execution. This study seeks to assess if open prisons can act as a sustainable and compassionate substitute for traditional incarceration by examining judicial precedents, empirical evidence, and global models.

Historical background

The development of the open prison system originates in the early 20th century, emerging from the increasing awareness that conventional custodial facilities were not meeting the objectives of rehabilitation and reform. The idea originated from the reformative branch of penology, which focused on rehabilitating the offender instead of solely punishing the crime. Globally, the concept became more significant in Europe, especially in Scandinavian nations such as Norway and Sweden, where open prisons were established to make incarceration more humane and lower recidivism rates. These systems aimed at reintegrating offenders by promoting community-based living, job access, and ongoing family connections. In India, the initial recognized open prison was set up in 1905 in Assam, called the Nalbari Open Jail, mainly to accommodate convicts engaged in agricultural work and who showed good behavior. The open prison model did not achieve substantial progress until after independence, at which point penal reform became a national priority.

The Indian prison system, significantly shaped by colonial regulations like the Prisons Act of 1894, was initially founded on the retributive model. However, due to the suggestions from several prison reform committees and the involvement of the judiciary, there was a growing acknowledgment of the necessity for a transition to a rehabilitative and reformative strategy. A major landmark took place in 1953, when the Indian Government established the All India Jail Reforms Committee (often called the Mulla Committee in 1980), which emphasized the necessity of reform-focused imprisonment and suggested the creation of additional open prisons nationwide. Rajasthan played a leading role by setting up numerous open camps and incorporating agricultural and vocational activities to assist inmates in earning a living. Currently, Rajasthan has more than 40 open prisons, positioning it as the leading state in embracing this model.

Concept and Objective

Open prisons, often referred to as minimum-security or reformative institutions, represent an innovative alternative to traditional correctional facilities, aimed primarily at reintegrating offenders into society by fostering trust, responsibility, and self-discipline. In contrast to conventional prisons where inmates experience constant monitoring, physical restrictions, and a strictly regulated atmosphere, open prisons permit chosen inmates—typically those with a history of good conduct, non-violent crimes, and nearing their release date—to reside in an unlocked, community-oriented environment with limited oversight. Inmates are frequently allowed to participate in work, farming, or vocational training outside the prison during the day, returning in the evening. This system is based on the assumption that these inmates present a low risk to society and that they have demonstrated the ability to rehabilitate.

The main goal of open prisons is reformation and rehabilitation instead of punishment. Their goal is to cultivate a sense of personal accountability in the inmate, allowing them to operate autonomously and engage meaningfully in society while still completing their time. The model aims to connect the divide between incarceration and complete reintegration by developing an atmosphere that reflects genuine responsibilities, like earning a living, sustaining family relationships, and engaging in community life. Open prisons notably alleviate the psychological distress linked to imprisonment by fostering mental health, dignity, and self-determination. Moreover, this system is essential for alleviating prison overcrowding and easing the financial strain on the state by lowering infrastructure and security expenses.

Essentially, open prisons embody the wider transition from retributive justice to rehabilitative and restorative justice, which corresponds with constitutional tenets found in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution that ensure the right to life and dignity for individuals even while incarcerated. Their aim is not solely to penalize but to equip inmates for a lawful existence upon their release—making sure that incarceration serves as a pathway to constructive change instead of social estrangement.

Legal Framework

The legal framework for open prisons in India is still evolving and does not have a comprehensive, singular law. The primary law governing prisons in India is the Prisons Act of 1894, a colonial-era statute focused on security, order, and the administration of conventional prisons. Regrettably, this Act lacks any clauses specifically addressing the creation or regulation of open prisons, underscoring the necessity for legislative reform to align with contemporary correctional philosophies. Nonetheless, the groundwork for open prisons has been established via state prison guidelines, court rulings, and policy papers, indicating a decentralized and state-oriented method for their execution.

The Model Prison Manual, 2016, released by the Ministry of Home Affairs, offers a modern framework advocating for the creation of open prisons within a broader reformation strategy. It identifies open prisons as facilities for inmates exhibiting positive behavior and minimal risk, proposing distinct eligibility standards that include age, behavior, health, and the type of offense committed. The Manual promotes skill enhancement, work-release initiatives, and community participation—thus supporting the rehabilitative objectives of open prisons. Even though it is not legally enforceable, it acts as a framework for state authorities to develop and execute prison reforms. Certain forward-thinking states such as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Kerala have revised their prison regulations to include open prisons, establishing eligibility criteria, conduct rules, and management frameworks.

Judicial interpretations have significantly contributed to providing legal legitimacy to open prisons. In various cases, the Supreme Court of India has stressed the importance of safeguarding the fundamental rights of prisoners as outlined in Article 21 of the Constitution, which assures the right to life and personal freedom. In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration (1978), the Court vehemently criticized cruel prison conditions and endorsed the rehabilitative purpose of imprisonment. Likewise, in Ramamurthy v. State of Karnataka (1997), the Court recognized overcrowding and insufficient reform as significant problems and promoted alternatives such as open prisons. These instances, while not explicitly legislating on open prisons, have established principles that advocate for their existence and growth.

Additionally, organizations such as the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and suggestions from several committees, including the Mulla Committee (1980-83) and the Justice Krishna Iyer Committee, have supported open prisons as a compassionate and efficient approach that complies with international norms and the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules). The lack of a consistent central law or mandatory guideline across all states has led to inconsistent adoption and restricted development of the open prison model in India. Consequently, there is an increasing need for specific national legislation or a revision of the Prisons Act to officially include the idea of open prisons and establish a coherent, rights-oriented framework for their functioning.

Advantages of Open Prison

Open prisons provide numerous important benefits that position them as a favorable approach within the context of reformative justice. One of the main advantages is their capacity to encourage the rehabilitation and reintegration of inmates into society. Open prisons foster a sense of responsibility and self-esteem in inmates by permitting them to work, stay connected with family, and reside in a less confined setting. These environments replicate actual circumstances, equipping inmates to transition to typical social conditions after release, thus lowering the likelihood of reoffending. A significant benefit is the alleviation of overcrowding in traditional prisons—a persistent problem in India. Open prisons can alleviate this pressure by accommodating well-behaved and low-risk offenders separately, enabling traditional prisons to concentrate on higher-risk inmates.

Open prisons are significantly more economical than closed prisons. The facilities are basic, security needs are diminished, and prisoners frequently assist through work or job training, lowering their maintenance expenses. For instance, while the state spends about ₹3,000 for each inmate in closed prisons, the expense in open prisons such as those in Rajasthan drops to roughly ₹500 per inmate. Furthermore, individuals in open prisons can earn income and assist their families, thereby alleviating the financial and emotional burden on their dependents. These prisons also promote mental health, as the liberty, open areas, and opportunity to participate in purposeful activities foster a healthier atmosphere compared to the frequently harsh and dehumanizing settings in closed facilities. Moreover, open prisons represent the constitutional principles of dignity, freedom, and equality, showcasing the reformative goals intended by Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Disadvantages of Prison

Although their innovative design is commendable, open prisons have their own disadvantages. One major concern is the possibility of escape, since these facilities function with limited physical security. Even though restricted to inmates demonstrating good behavior, the chance of escape or violation of conditions cannot be entirely excluded. This brings up issues related to public safety and confidence, particularly in regions where familiarity and approval of such models are minimal. A significant concern is that open prisons have a selective approach—they typically serve only non-violent, first-time offenders or individuals close to completing their sentences, thereby excluding a substantial segment of the prison population. This restricts their usefulness and influence in tackling the larger challenges within the criminal justice system.

Challenges related to infrastructure and administration continue to exist. Numerous states do not possess the political commitment, resources, or qualified staff to successfully execute and oversee open prisons. Inconsistencies in eligibility standards, quality of services, and operational effectiveness arise due to the absence of a consistent policy among states. Moreover, public opinion frequently stays doubtful or unfavorable, featuring a societal prejudice towards prisoners that impacts the readiness of employers, communities, and officials to assist in the reintegration of inmates. Ultimately, in the absence of thorough national laws that clearly acknowledge and govern open prisons, their legal standing is disjointed and reliant on administrative judgment, potentially leading to misuse, bias, or unjust refusal of access for qualifying inmates.

Landmark Cases

The Indian judiciary has been crucial in influencing discussions on prison reform, the human rights of inmates, and the importance of implementing alternatives such as open prisons. While there is no Supreme Court ruling that specifically legalizes or requires the establishment of open prisons, various seminal decisions have established a foundation by highlighting reformative justice and the humane treatment of prisoners under Article 21 of the Constitution, which ensures the right to life and personal liberty. In Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration (1978), the Supreme Court denounced solitary confinement and custodial abuse, emphasizing that prisoners remain human beings and are entitled to constitutional rights. Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer aptly noted that the prison walls should not obscure the judiciary’s awareness of the pain experienced by inmates. This case established the foundation for a more empathetic and restorative method to incarceration.

In Ramamurthy v. State of Karnataka (1997), the Supreme Court observed various shortcomings in the prison system, such as overcrowding, poor hygiene, and insufficient reformative initiatives. The Court encouraged the state to adopt progressive penal methods and highlighted the necessity for options such as open prisons to alleviate overcrowding and enhance rehabilitation. In the case of Charles Sobhraj v. Superintendent, Central Jail, Tihar (1978), the Court reaffirmed that prison discipline should not infringe on fundamental rights and endorsed the principle of dignity and humane treatment for inmates. A notable case is State of Rajasthan v. Union of India (2006), where a PIL addressed the scrutiny of prison management regarding jail conditions. Even though it’s not exclusive to open prisons, the Court endorsed state-level independence in creating innovative prison models, including the open prison system that has been effectively used in Rajasthan.

These judgments, along with multiple High Court actions and suggestions from organizations such as the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the Mulla Committee, have established a robust legal basis for supporting open prisons. They demonstrate a steady judicial tendency favoring reform over punishment and indirectly endorse the validity and necessity of open prisons as a viable, humane, and constitutionally acceptable form of incarceration.

The idea of open prisons signifies a significant change in India’s penal philosophy, transitioning from punishment to rehabilitation and reform. This study has examined how open prisons provide a compassionate and economical option to conventional imprisonment by focusing on trust, accountability, and the reintegration of inmates into the community. They help to alleviate overcrowding in prisons and lower operational expenses, while also maintaining the dignity of inmates and equipping them for a lawful, productive life after release. The effective establishment of open prisons in regions such as Rajasthan and Maharashtra highlights the promise of this model in tackling systemic shortcomings within India’s criminal justice system.

Nonetheless, even with their potential, the expansion and acceptance of open prisons continue to be restricted by administrative stagnation, legal uncertainty, public doubt, and infrastructural issues. The lack of a thorough legal structure or central laws has resulted in uneven application among states. Additionally, social stigma and safety issues remain barriers to the broader acceptance of this model. To unlock the complete potential of open prisons, it is crucial for policymakers to implement a rights-based, consistent policy framework that distinctly specifies eligibility, operational standards, and protections against misuse.

Conclusion

The idea of open prisons signifies a transformative change in India’s penal approach, transitioning from retribution to rehabilitation and reform. This study has demonstrated that open prisons provide a compassionate and economical substitute to conventional incarceration by focusing on trust, accountability, and the reintegration of inmates into the community. They help not only to alleviate prison overcrowding and cut operational expenses but also to maintain the dignity of inmates and ready them for a lawful, productive life after release. The effective execution of open prisons in various states exemplifies the promise of this approach in tackling systemic flaws within the Indian criminal justice system.

Nonetheless, despite their potential, the expansion and acceptance of open prisons continue to be restricted by bureaucratic inertia, legal uncertainty, public doubt, and infrastructural obstacles. The lack of a thorough legal framework or unified legislation has resulted in uneven enforcement among states. Furthermore, social stigma and safety issues persist in hindering the broader acceptance of this approach. To unlock the complete capabilities of open prisons, it is essential for policymakers to implement a rights-centered, consistent policy framework that distinctly defines eligibility, operational criteria, and protections against abuse.

The Indian legal system has consistently supported the reformative nature of justice, stressing that inmates maintain their basic rights, such as the right to dignity as stated in Article 21 of the Constitution. In this regard, open prisons should not be viewed as a luxury, but rather as a vital element of an advanced justice system. With proper legal support, public awareness, and institutional backing, open prisons can develop into a viable and efficient framework for penal reform in India—congruent with constitutional principles and international human rights norms. Consequently, open prisons represent not just a feasible model but an essential one in the pursuit of a more compassionate and restorative criminal justice system.

References

- https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-analysis/open-prisons-in-india

- https://www.barandbench.com/view-point/beyond-bars-understanding-potential-of-open-prisons-india

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_prison

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is personal.

0 Comments