Introduction:

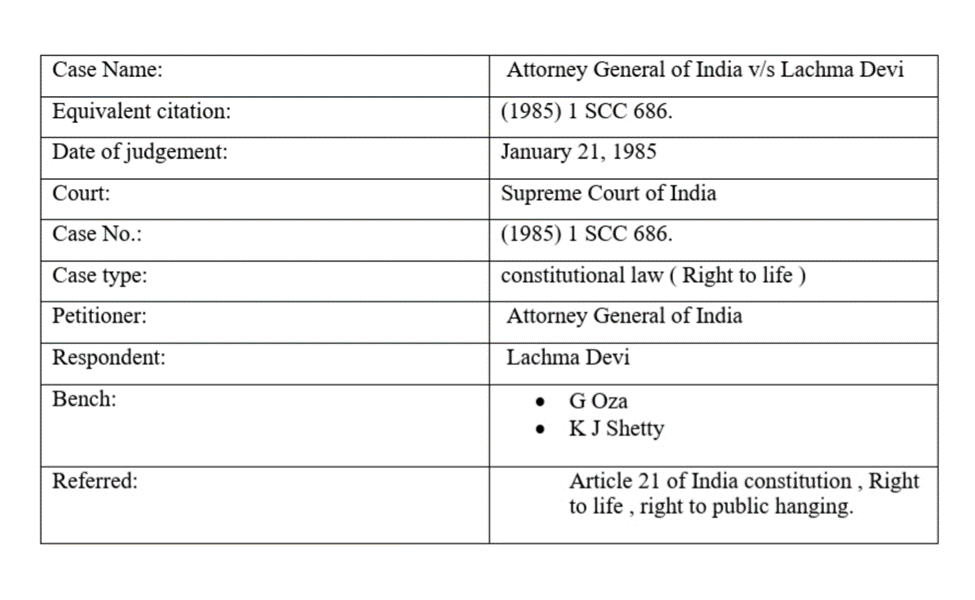

Attorney General of India v/s Lachma Devi is a significant case that deals with the right against public hanging, and it was decided by the Supreme Court of India in 1985. This case raised several legal questions related to the constitutionality of public hanging and the right to life and personal liberty guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. In this case analysis, we will discuss the facts of the case, the legal issues involved, the arguments put forth by both the parties, and the judgment of the court.

Facts of the case:

Lachma Devi was convicted of murder and sentenced to death by hanging by the Additional Sessions Judge of Bikaner, Rajasthan. The Rajasthan High Court upheld her conviction and sentence. However, Lachma Devi filed a writ petition under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution challenging the constitutionality of public hanging.

Legal issues:

The primary legal issue in this case was whether the practice of public hanging was constitutional, and whether it violated the right to life and personal liberty guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. Additionally, the court also examined the question of whether public hanging was an essential part of the criminal justice system in India.

Arguments of petitioner:

The Attorney General of India argued that public hanging was a necessary part of the criminal justice system, and it acted as a deterrent to crime. The Attorney General argued that the Constitution of India did not prohibit capital punishment, and the mode of execution was left to the discretion of the legislature. Additionally, the Attorney General contended that public hanging was a long-standing practice in India and was consistent with the cultural and social values of the country.

Argument of respondent:

Lachma Devi’s argument was that public hanging was a barbaric and inhumane practice that violated her fundamental rights under the Indian Constitution. She argued that the act of public hanging was a cruel, degrading, and inhuman punishment that was inconsistent with the constitutional principles of dignity and humanity. Additionally, Lachma Devi contended that public hanging was a form of torture that was prohibited under international law, and India had ratified various international conventions that prohibited torture.

Ratio Decidendi:

The Court noted that while the State has the power to impose the death penalty, it must do so in a manner that is consistent with human dignity and not in a way that subjects the convict to unnecessary suffering or degradation. The Court further held that the use of the gallows for execution, particularly in public, is a barbaric practice that has no place in a civilized society.

Therefore, the ratio decidendi of this case is that the right to life under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution includes the right to die with dignity and that public hanging is a degrading and inhuman form of punishment that violates this right.

Judgment of the court:

The Supreme Court of India delivered its judgment in favor of Lachma Devi and held that public hanging was unconstitutional and violated the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Indian Constitution. The court observed that public hanging was a barbaric and inhumane practice that was inconsistent with the principles of dignity, humanity, and the right to life and personal liberty. The court also held that the act of public hanging was a cruel and degrading punishment that violated the constitutional prohibition against torture.

The court also rejected the argument put forth by the Attorney General of India and held that the mode of execution was not left to the discretion of the legislature. The court observed that the right to life and personal liberty was a fundamental right that could not be taken away except by a procedure established by law. The court held that the procedure established by law must be fair, just, and reasonable, and it must not be arbitrary, discriminatory, or violative of the principles of natural justice.

The court further observed that the right to life and personal liberty included the right to die with dignity, and the act of public hanging violated this right. The court held that the dignity of the individual was an essential aspect of the right to life and personal liberty, and public hanging was inconsistent with this principle.

Significance:

The judgment in the case of Attorney General of India v/s Lachma Devi was a landmark in the history of Indian criminal jurisprudence. It upheld the sanctity of the right to life and dignity of every individual, even in the case of a convicted criminal. It also recognized the duty of the State to ensure that the execution of the death penalty was carried out in a manner that was consistent with human dignity. The judgment also marked the end of the practice of public hangings in India.

Conclusion:

The case of Attorney General of India v/s Lachma Devi 1985, dealt with the controversial issue of the right to public hanging in India. The case was brought to the Supreme Court of India to determine whether the public hanging of a convicted murderer could be considered a violation of their fundamental rights.

The Supreme Court held that the right to life under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution does not include the right to die, and that the imposition of the death penalty by hanging is a constitutional means of punishment. However, the Court also held that the right to human dignity and the prevention of cruelty under Article 21 must be upheld, and that a public hanging could be considered a violation of these rights.

Thus, the Court established guidelines for the execution of the death penalty, including that it should be carried out in private, and that the condemned should be allowed to meet with their family and lawyers prior to their execution.

Overall, the case of Attorney General of India v/s Lachma Devi o1985, highlights the delicate balance between the right to punishment for a crime and the protection of fundamental human rights. The guidelines established by the Court have since been followed in the execution of the death penalty in India.

This is written by Muskan Kumari of The ICFAI Univeristy, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

0 Comments