This article is written by Nandan Rathi of 10th Semester of Hidayatullah National Law University, Chhattisgarh, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

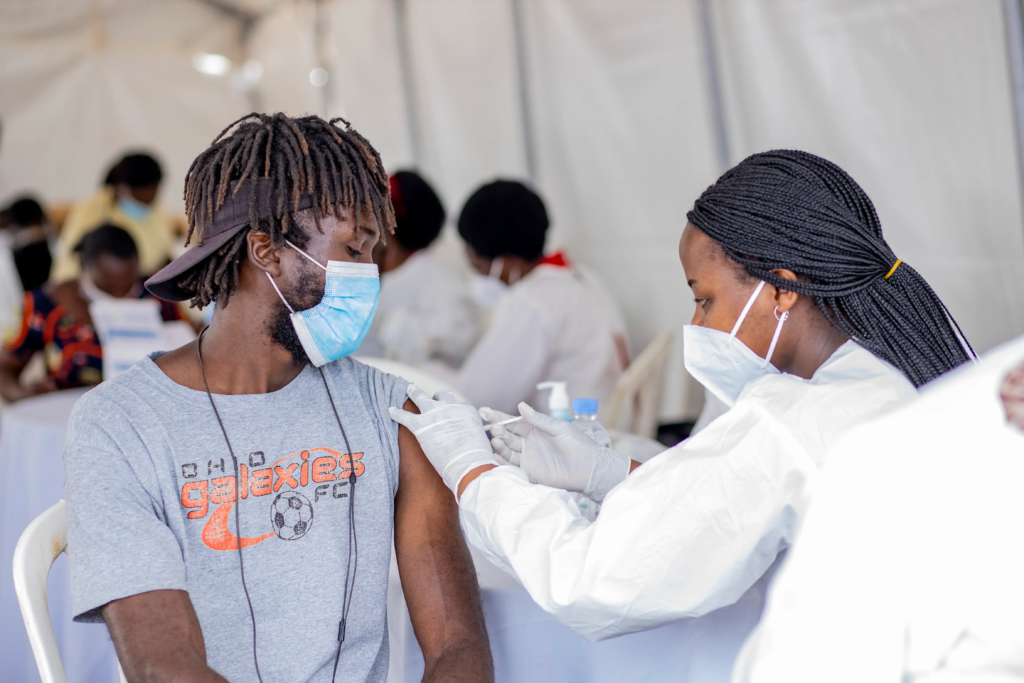

Healthcare for all is the basic priority of the government. The state must ensure that every individual gets access to medicines, and healthcare facilities in the time of outbreak of any deadly disease or virus. However, there exists a great inequality as the richer countries have better access to critical vaccines and medical supplies, highlighting disparities with poor countries. Historically and even today developed nations continue to exploit low-income countries by hoarding and restricting the essential supply of vaccines. Organizations like the WHO work to ensure vaccine equity. Despite the efforts, many countries have struggled to get fair vaccine access and suffer devastating consequences. This article seeks to explore the importance of vaccine equity, various international law approaches to vaccine equity, challenges faced in ensuring equity, and suggestions that can help in achieving equality.

Keywords

Vaccine, Health, Covid-19, WHO, Equity

INTRODUCTION

Widespread diseases are prevalent in the society. Whenever there is a huge outbreak of a new disease whose cure is not readily available, the only hope that remains to fight against the disease is a vaccine. When a disease is spread across vast regions affecting a large population it is said to be a pandemic, whose cure may or may not be available. As a result, scientists, doctors, and other health experts face the huge challenge of developing a vaccine to control the spread of a pandemic. The rate at which a disease spreads is much faster than the time to create the vaccine. Even if the vaccine is made quickly, giving the vaccine to people on such a large scale is a big task. Vaccines are easily available in developed countries and rich people can easily afford them. Poor and marginalized people living in backward regions do not receive the vaccines timely. This undermines the equality of treatment and results in vaccine inequality. In international law, there is a concept of vaccine equity which ensures that the wide population gets access to vaccines, critical for their survival.

Meaning of Vaccine Equity-

‘Vaccine equity means the fair allocation of vaccines, guaranteeing that every person regardless of their socioeconomic, location, or financial means, has the same access to life-saving vaccinations. It focuses on vulnerable and high-risk groups, especially in low-income nations, to tackle healthcare access and results inequities. Vaccine equity is founded on the ideals of human rights, international solidarity, and the acknowledgment of vaccines as global public assets.’[1]

INTERNATIONAL LAW PERSPECTIVES ON VACCINE EQUITY

International law viewpoints regarding vaccine equity include principles, duties, and structures derived from treaties, customary international law, human rights law, trade deals, public health governance, and global solidarity. The matter of vaccine equity encompasses intricate legal, ethical, and political factors within the framework of international law.

HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORK-

Vaccine equity is based on the acknowledgment of health as a basic human right according to international.

Right to Health-

Legal Basis-

‘Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), acknowledges the entitlement to a sufficient standard of living, encompassing healthcare.’[2] ‘Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) mandates that nations guarantee the highest possible physical and mental health standards and access to essential medicines and vaccines.’[3]

Key Features-

Availability- Vaccines must be provided to people in adequate amount

Accessibility- Vaccines should be available without discrimination both in terms of physical access and financial cost.

Acceptability– Vaccines ought to be ethically and culturally acceptable.

Quality– Vaccines must adhere to scientific and medical criteria.

Duties of Nations-

Nations hold a dual obligation-

Domestic– Guarantee fair vaccine distribution for their communities. Global- Collaborate to guarantee fair vaccine distribution worldwide, especially for at-risk groups.

“General Comment No 14- 2000

The Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights underscores that access to vital medications, including vaccines, to marginalized people is a fundamental duty of governments. Inequity in vaccine allocation breaches this responsibility.”[4]

Fundamentals of Global Collaboration and Unity-

The responsibility of states to work together in tackling global issues strengthens vaccine equity.

‘Articles 55 and 56 of the United Nations Charter-

These articles encourage collaboration to address global health issues and uphold human rights.’[5]

“Constitution of World Health Organization (WHO)

The introductory section of the WHO Constitution emphasizes that the right to the highest possible standard of health is a fundamental right of every individual.”[6]

“Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)

SDG 3 seeks to guarantee healthy lives and foster the well-being of everyone, which includes universal vaccine access.”[7]

According to ‘Article 2(1) of the ICESCR’, countries must work together on an international level to progressively fulfill economic, cultural, and social rights, which encompass health-related objectives.

“The Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR)-

This principle is acknowledged in international environmental law, especially regarding sustainable development, CBDR can be applied to vaccine fairness.”[8] Richer countries and pharmaceutical companies have a larger obligation to guarantee equitable vaccine distribution because of their resources and abilities.

Trade and Intellectual Property Structure-

The convergence of trade and public health is essential for grasping the challenges of vaccine equity.

‘Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ACCORD’ (TRIPS)

Patent Safeguard–

The TRIPS Agreement offers patent safeguards for vaccines, frequently restricting low-income nations from manufacturing cost-effective alternatives.

Flexibility options-

Compulsory Licensing– ‘Article 31 of TRIPS’ permits the government to allow the manufacturing of patented goods without the patent’s owner’s permission in times of public health crisis.

Doha Declaration (2001)- Confirmed the rights of nations to utilize TRIPS flexibilities to emphasize public health.

Debate on TRIPS Waiver-

Introduced by India and South Africa amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRIPS waiver aimed to temporarily halt intellectual property protections for vaccines, facilitating an increase in production and distribution. The discussion highlights conflicts between intellectual property rights and public health needs.

Worldwide Health Management–

Global Organizations are crucial in tackling vaccine equity issues.

World Health Organization (WHO)-

COVAX Initiative– led by WHO, Gavi, and CEPI, COVAX seeks to provide fair vaccine access.

‘International Health Regulations (2005), is obligatory for WHO members and creates a framework for global cooperation during public health crises. The IHR highlights the importance of global cooperation in health crises, yet they do not include explicit measures for vaccine fairness. The IHR does not tackle the fair allocation of vaccines and highlights the shortcomings in global health governance.’[9]

UN Human Rights System-

Special Rapporteurs– Promoted Vaccine as a global public asset and urged for fair distribution.

Universal Periodic Review– Evaluate state adherence to human rights commitments concerning vaccine equity.

Multilateral Monetary Institutions–

Organizations like the IMF and World Bank can offer financial support and debt alleviation to assist low-income nations in acquiring vaccines.

Customary International Law and Developing Standards-

‘Principle of Solidarity’– While not universally documented, solidarity is a rising concept encouraging nations to distribute resources, such as vaccines, amidst global emergencies.

Global Public Goods– Vaccines are increasingly recognized as public goods that necessitate collective responsibility.

Impact of COVID-19 on Vaccine Equity-

The COVID-19 Pandemic emphasized worldwide inequalities in vaccine distribution. Wealthy Countries (HNIs) obtained vaccines more readily and in larger amounts than poorer countries (LINs), highlighting fundamental disparities in global health management, resource allocation, and infrastructure preparedness.

Vaccine Accumulation by Wealthy Countries-

Advance Purchase Agreements– Affluent countries placed advanced orders for billions of vaccine doses, frequently surpassing their population requirements. For example, Canada acquired doses enough to vaccinate its population several times.

Stockpiling- Nations Postponed contributions to international programs like COVAX, focussing on booster shots for their citizens as Low-income nations faced challenges in vaccinating health workers at risk.

Obstacles to Access for Low-Income Countries–

Production Limitations– Vaccine manufacturing is focused in High-Income Nations preventing poorer countries from getting access to critical medical supplies and vaccines.

Intellectual Property Protections– Patents established by the TRIPS agreement imposed legal and economic obstacles for generic manufacturing in developing countries.

Logistical Issues– numerous low-income level countries were without cold-chain systems and qualified staff to administer vaccines effectively.

Worldwide Initiatives and their Constraints-

COVAX: Created to guarantee fair vaccine distribution, but COVAX struggled with funding shortages, supply setbacks, and inadequate support from developed countries, failing the initiatives as it failed to meet its target requirements.

Vaccine Donation– Contribution from rich nations frequently came with brief shelf lives, adding to the challenges of already constrained distribution capabilities in underdeveloped regions.

Impact-

‘By the middle of 2022, when the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was over, more than 70% of the population living in high-income nations were vaccinated compared to just 10% in African countries. This inequality extended the pandemic and heightened global susceptibility to new variants.’[10]

Indian Success Story-

When the pandemic hit India around March 2020, it was assumed that the country was not prepared to tackle such widespread diseases. Initially, India faced a shortage of oxygen cylinders, vaccine doses, and medicines to tackle the virus. After the devastating second wave of the pandemic, India managed to develop its vaccines. The most impressive feat of making these vaccines was in such record time to cater to the needs of 1.4 billion people. It was estimated that it would take India years to give vaccines to every citizen. India managed to get the majority of its population vaccinated in such a short period. Another impressive thing was that India exported the vaccine to more than 150 countries highlighting India as a major player in pharmaceuticals and reaffirming the importance of vaccines. Even the US and European countries got help from India during the pandemic to get a seamless supply of vaccines.

Instances from History that Highlight Vaccine Inequality-

H1N1 Influenza Outbreak (2009)-

During the H1N1 Pandemic, the developed nations acquired significant amounts of vaccines restricting the poorer countries from getting easy access to vaccines. It was for the intervention of the World Health Organization to facilitate the agreement between vaccine producers to manufacture vaccines for countries most affected by the outbreak. However, the vaccine distribution did not go according to the plan as many vaccines were holdups resulting in vaccines getting delayed and reached when the virus was on the brink.

Ebola Virus Epidemic (2014-2016)

Experimental Ebola vaccines were developed and expedited during the West Africa Outbreak. Despite this the logistical issues and delayed funding limited the countries to access the hardest hit regions from the virus. Vaccines mainly targeted healthcare workers instead of the general public, highlighting disparities in resource distribution during a crisis.

Initiatives for Polio Elimination-

Polio Vaccination efforts encountered unequal access stemming from geopolitical tensions, misinformation, and insufficient infrastructure in specific areas such as regions of Africa and South Asia. Affluent countries managed to eradicate polio swiftly, whereas poorer countries needed decades of hard work and considerable geopolitical assistance.

Crisis of HIV/ AIDS-

The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the 1990s transformed HIV/AIDS treatment while exposing significant disparities. Developed nations had broad access to life-saving medications. Whereas African countries, where most people affected by HIV lived, struggled with exorbitant prices and restricted availability of vaccines and other essential medical supplies. International programs and the Global Funds ultimately enhanced the access to vaccines.

Yellow Fever Epidemics-

The recurrent pattern of yellow fever outbreaks in Africa has consistently pressured vaccine stocks while rich countries are rarely impacted. For example, in 2016, the outbreaks in Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, worldwide vaccine reserves were almost depleted, which postponed the reactions and increased the risks of wider transmission.

Obstacles to Vaccine Fairness in Global Law-

Vaccine Nationalism– Richer countries focusing on their population at the expense of others hinder efforts for global equity.

Absence of Enforceable Mechanisms– Current international frameworks do not have binding clauses to guarantee vaccine equity thus there is a need for legal enforcement.

Private sector control– The profit-oriented approaches of pharmaceutical firms clash with objectives for public health.

Funding Shortfalls– Programs such as COVAX depend on voluntary contributions, which frequently fall short.

Actions to Decrease Vaccine Disparity-

Enhancing Global Leadership for Health Equity-

Establishing Legally enforceable treaties- Creating global agreements that require fair vaccine distribution in health emergencies, guaranteeing that every nation, particularly low-income ones, obtains in rightful proportion.

Ensuring Fair Distribution Systems-

By enhancing models such as the World Health Organization’s Fair Allocation vaccine to guarantee clear, needs-driven allocation can be achieved.

Putting money into Local Production facilities–

Decentralized vaccine manufacturing– create vaccine production centers in underdeveloped countries to lower their dependence on developed countries.

Technology Transfer– Enable sharing of technology and knowledge from pharmaceutical firms in developed nations to manufacturers in developing countries.

Revamping Intellectual Property Regulations-

TRIPS Waiver– Suspend intellectual property rights temporarily during pandemics to enable local vaccine production.

Voluntary licensing Patent Tools– Promote initiatives such as the “WHO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP)”[11] to facilitate the voluntary sharing of patents and technologies related to vaccines.

Securing Financial Support and Cost-Effectiveness

Global Vaccine Financing– By enhancing funding structures like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the ‘Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI)’[12] to support vaccine availability for low-income nations

Graduated Pricing Models-

Establish pricing frameworks that ensure vaccines are accessible for nations with varying income levels.

Enhancing Infrastructure and Readiness-

Cold Chain Expansion– Allocate resources to cold chain logistics to guarantee the transport and storage of vaccines in less developed countries.

Training for Healthcare Workers- Create initiatives to instruct staff on vaccine administration and handling extensive immunization efforts.

Promoting Worldwide Unity-

Vaccines as Global Public Goods–

Advocate for the concept that vaccines should be viewed as public goods rather than commodities and should be distributed fairly.

Proactive Contribution– Motivate developed nations to pledge their surplus vaccine doses via established channels such as COVAX.

Oversight and Responsibility-

Clarity in distribution- mandate nations and producers to reveal vaccine supply contractors and distribution strategies.

Worldwide Monitoring Organization– create autonomous entities to oversee vaccine distribution fairness and ensure countries uphold their obligations.

The Influence of Health Organizations on Developing Vaccine Equity–

World Health Organization–

Norm Establishment and Coordination- Create and execute global frameworks for vaccine distribution, like the Fair Allocation Framework.

Global Health Leadership–

Serve as the primary organization for orchestrating global responses making certain that nations follow fair distribution guidelines.

Technical Assistance– Offer Aid to underdeveloped and developing countries in formulating vaccine distribution plans, encompassing training, logistics, and supply chain management.

Advocacy– Push for vaccines to be recognized as global public goods and support changes in intellectual property laws.

‘Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI)’-

Speeding up vaccine creation- providing funding and organizing research for vaccines aimed at potential pandemic risks.

Equitable Access Management– By making certain that the vaccine contracts have provisions that ensure access to everyone.

UNICEF and Non-Governmental Organizations-

Logistical Assistance– Aid in the distribution of vaccines in isolated and underfunded regions.

Community Involvement– inform communities about the significance of vaccination and tackle vaccine reluctance.

Local Health Organization–

Decentralized coordination– Entities like the Africa CDC of the African Union can spearhead regional vaccination efforts, including the ‘Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM).’[13]

Collaboration in Private Sector-

Public-Private Partnership– Work alongside pharmaceutical firms to speed up vaccine creation, guarantee affordability, and promote technology transfer.

Corporate Social Responsibility– Motivate private sector involvement, such as financial support and expertise, to enhance global health projects.

CONCLUSION

Vaccine equality is an essential measure of global unity and collaboration. Although International law provides certain tools to tackle this issue, there are still gaps that need normative advancement and more robust implementation mechanisms. The COVID-19 pandemic was a pivotal event that revealed and worsened vaccine disparities. Historical trends indicate that this inequality is not a recent phenomenon but rather systemic, requiring fundamental changes in global health governance and the prioritization of equity in upcoming health emergencies. If the change does not take place now, it will be a bigger problem for future generations and any pandemic may further create a divide in getting access to life-saving medicines. Thus, only the collective efforts from the states will ensure that this disparity will be eliminated and everyone will be better prepared in times of adversary.

[1] Liao, K. (2021). What Is Vaccine Equity and Why Is It So Important? [online] Global Citizen. Available at: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/what-is-vaccine-equity-covid-19/.

[2] United Nations (2018). Universal Declaration of Human Rights at 70: 30 Articles on 30 Articles – Article 25. [online] OHCHR. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2018/12/universal-declaration-human-rights-70-30-articles-30-articles-article-25.

[3] United Nations (1966b). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

[4] UNHR (n.d.). OHCHR | e) General Comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 12) (2000). [online] OHCHR. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/resources/educators/human-rights-education-training/e-general-comment-no-14-right-highest-attainable-standard-health-article-12-2000.

[5] Falk, G.T. (2025). United Nations Charter (1945). [online] Cirp.org. Available at: https://cirp.org/library/ethics/UN-charter/

[6] World Health Organization (2024). Constitution of the World Health Organization. [online] World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution.

[7] United Nations (2015). The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

[8] hey, E. and Paulini, S. (2021). Common but Differentiated Responsibilities. [online] Oxford Public International Law. Available at: https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1568.

[9] World Health Organization (2024b). International Health Regulations. [online] www.who.int. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/international-health-regulations#tab=tab_1.

[10] United Nations (2022). UN analysis shows link between lack of vaccine equity and widening poverty gap. [online] UN News. Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1114762.

[11] WHO (2020). COVID-19 technology access pool. [online] www.who.int. Available at: https://www.who.int/initiatives/covid-19-technology-access-pool.

[12] India Science, Technology and Innovation Portal (2024). IND-Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) | India Science, Technology & Innovation – ISTI Portal. [online] Indiascienceandtechnology.gov.in. Available at: https://www.indiascienceandtechnology.gov.in/programme-schemes/research-and-development/ind-coalition-epidemic-preparedness-innovations-cepi

[13] Africa CDC (2022). Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) Framework for Action. [online] Africa CDC. Available at: https://africacdc.org/download/partnerships-for-african-vaccine-manufacturing-pavm-framework-for-action/.

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is personal.

0 Comments