This article is written by Krishna Raj, a final year LL.B student from Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Law University, Jaipur. The article discusses about various conditions restricting transfer in property law of India.

Keywords: Indian Property Law, Transfer of Property, Restrictions on transfer of Property.

Introduction

The Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (TPA), the Indian Registration Act, 1908, the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, and several state-specific legislations all regulate property law in India. Particularly, the TPA establishes the fundamental basis for property transactions in the nation. It outlines what counts as property, the various kinds of transfers, the parties’ rights and obligations, and the circumstances in which they may occur. The existence of encumbrances on the property is one of the most significant restrictions on transfer in property law.

Encumbrances are restrictions or legal obligations that impact a property’s title. They could be liens, easements, leases, mortgages, charges, and any other types of claims that could prevent the property from being transferred. These encumbrances may result from a number of different things, including contracts, judicial orders, legal requirements, or even customary laws.

Encumbrances on a property might prevent transfer in a number of different ways. Due to the buyer’s possible unwillingness to take on the encumbrances or requirement that they be removed before closing the deal, it may restrict the owner’s ability to sell or otherwise dispose of the property.

This article focuses only on the conditions restricting transfer of property as per the provisions of the transfer of property act, 1882.

Basics of Transfer of Property

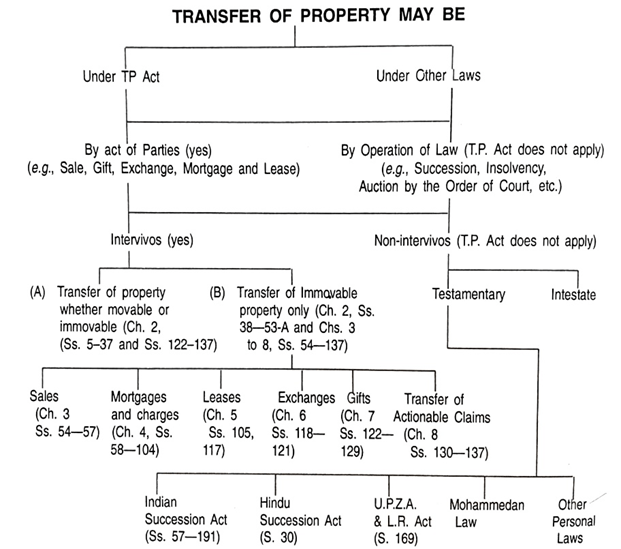

Property transfer is a concurrent subject[1], meaning that both the central government and state governments may pass legislation related to it, with the exception of land used for agriculture, which is a state subject.[2] The Transfer of Property Act, 1882 aims to establish general rules for property transfers.

According to Section 5 of the Transfer of Property Act, a transfer of property is any act by which a living individual transfers property to one or more other living individuals for use in the present or for use in the future. Living persons also refers to organizations, associations, and groups of people, whether or not they are incorporated.

Transferor and Transferee are the parties engaged in the transfer of property. The most significant area of civil law is the law dealing to the transfer of property. The Indian Succession Act, 1925 will apply if the property is transferred or disposed of through a will rather than the Transfer of Property Act, 1882.

Although both types of property are covered by Chapter II of the Act. The Act’s requirements would not apply in the event that the Transfer occurs by operation of law. [3]The term “operation of law” refers to a transfer through inheritance, insolvency, forfeiture, or sale in accordance with a court order. The transfer of property must follow the guidelines established by this Act.[4]

Table showing possible transfers of a property

Types of conditions restricting transfer of property

1. Restraints on transfer for a particular time

Time restrictions, such as the requirement that the transferee not sell it for five years, ten years, or any other period of time, are invalid, unless they are for a brief time period and come with a benefit to the transferor, like an option to repurchase at a price specified in the contract. This transferor’s only and exclusive right to exercise the buyback option does not apply to anybody else.

2. Restraints directing control over consideration/money

When the transferor directs that the property should be transferred for no consideration, at market value only, or at any amount deemed appropriate by the owner, but out of the sale proceeds, either something has to be paid to a specific person or persons, or for a specific purpose, all of these conditions would be restrictions on alienation through transfer. Such requirements cannot be imposed by the former owner or holder. These restrictions would be null and unlawful since they would amount to an absolute restraint on the transferee’s freedom to alienate the property. For example, A sells a house to B for Rs. 10,000 with a condition, that if in future B wants to sell it, he would sell it only for Rs. 10,000. This condition would be void, and B may sell it for any consideration.[5]

3. Restraints with respect to persons/transferee

Depending on the precise facts and circumstances of the case, restrictions telling the owner that the property or an interest in the property should be transferred to particular people might be either partial or absolute. Such a condition would be null and void where the transferor tells the transferee that when he wants to sell the property, he must sell exclusively to a specific person mentioned by the transferor in the deed or to a group of persons. However, if the restriction is that he shouldn’t sell it to anybody outside of his family or even community, it will be seen as a partial restraint as long as both the transferor and the transferee are members of the same family or community. This kind of demand might arise from a wish to protect the property within a particular family or community, of which both parties are a part. Therefore, the transferor cannot impose a requirement that the purchaser sell the property only to members of the transferor’s family when the transferor himself sells the property to a third party.

4. Restraints with respect to sale for particular purposes or use of property

When the transferor expressly states that the property may only be transferred for a specific purpose and makes no apparent mention of the transferee’s ability to sell the property, this would also be a complete restraint on the transferee’s powers to transfer his interest as he sees fit. He is free to choose who and what he should sell to, and if a condition is ever added to the contract at the transferor’s request, he is allowed to disregard it. Conditions that the property must be sold only for a religious purpose, or for any other particular purpose, are therefore invalid since they violate the right of alienation.

Types of Condition

Condition may be condition precedent (Sections 25, 26), condition subsequent (Sections 31, 29), or collateral (Sections 27, 28). Section 10 is concerned with conditions subsequent under Sections 31 and 29. Condition for the purposes of Section 10 means condition subsequent which has the effect of divesting the interest which has otherwise vested in the transferee. If it bars transferee’s right to re-transfer, the condition is void.

The differences between condition precedent and condition subsequent is given below

| Basis | Condition precedent | Condition subsequent |

| Before/after transfer | Transfer is complete only after completion of condition precedent | Transfer gets invalidated if condition subsequent is not completed. |

| Interest | an interest once vested can never be divested because of non-fulfillment of some condition. | interest even though vested, can be divested because of the non-fulfillment of the condition. |

| Impossible to perform | transfer will be void if the condition precedent is impossible to perform, or immoral or opposed to public policy. | transfer becomes absolute and the condition will be ignored if that condition is impossible of performance or immoral or against public policy. |

| Doctrine of cy press (as close as possible) | the doctrine of cy press applies and the condition precedent is fulfilled if it is subsequently complied with. | The doctrine of cy press does not apply |

Restraints apparently partial but really absolute

The condition on alienation may be either absolute or partial. If it is absolute, it is null and void under Section 10. If it is only partial, Section 10 has no jurisdiction over it and it may nevertheless be legally binding. According to Section 10, a complete restriction on the right to transfer is null and void. If any transfer of any type is made, the transferee may transfer the property further whenever he chooses. If it is attempted to be controlled or banned by the first transferor with the help of condition, the condition fails by virtue of Section 10 and the transfer survives.

The test to distinguish in between partial and absolute restriction is “what remains with the transferee after the condition is enforced”. If it takes away the right to transfer substantially, it is absolute and void. If it leaves it substantially, it is partial and valid.[6]

The usual kind of partial restraint is the one that confines the exercise of the power to a particular person or class of persons. if it is restricted so as to be exercisable in favour of a specified individual only, the restriction is void and ineffective, i.e., transfer to A with restriction that he can transfer it only to X, transfer was valid; restriction void. It is obvious that if the introduction of one person’s name as the only person to whom the property may be sold, renders such a proviso invalid, a restraint on alienation may be created as complete and perfect as if no person permitted to purchase. For the person, who alone is permitted to purchase, might be selected as to render it reasonably certain that the property could not be alienated at all.

Case Laws on Property Law

1. Loknath Khound v. Gunaram Kalita, AIR 1986 Gau 52[7]

In this case, Gunaram Kalita was in dire need of money, he sold his property to Hatem Ali for Rs 1200/- with a condition that the land will reconvey to him after the payment of this amount within 5 years. The Gauhati High Court held that this is a valid condition because it is in the nature of a partial restraint and is for the personal benefit of the transferor.

2. Saraju Bala Debi vs Jyotirmoyee Debi, AIR 1931 PC 179[8]

In this case, the condition restraining transfer of property with respect to purposes or use of property was discussed and it was concluded by the court, that the conditions that the property should be sold for a religious purpose or for any other specific purpose only is void as being against the right of alienation.

3. Debi Dayal v. Ghasita, AIR 1929 All 667[9]

In this case, the plaintiffs sold their house to defendant for Rs. 175 and the latter agreed by an agreement to sell the house back to them for the same price Rs. 175 when the defendant wanted to transfer it and that only if the plaintiff declined to repurchase the house, he would sell it to other persons. The Allahabad High Court held that “This was a special personal contract between the parties which was binding on them and could be enforced against the transferees with notice but not otherwise.”

Conclusion

There are some instances that restrict the transfer of the property but overall, transferability is rule, sections 10 to 17 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 confirm that transferability of property is rule and non-transferability (Section 6) is an exception. The property has to be transferable. No condition can be imposed on further alienation (Section 10), enjoyment cannot be restrained (Section 11), interest given cannot be made determinable on insolvency or attempted transfer (Section 12), all these and other types of transactions are subject to the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 and no direction can be imposed for accumulation of income creating perpetuity in any other manner.

References

- Raj Kapadia, Restrain on Transfer of Property, Legal Service India, available at https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-4151-restrain-on-transfer-of-property.html, last seen on 13/04/2023

- Loknath Khound v. Gunaram Kalita, AIR 1986 Gau 52 available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/853636/, last seen on 14/04/2023

- Saraju Bala Debi v. Jyotirmoyee Debi, AIR 1931 PC 179 Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/469807/, last seen on 14/04/2023

- Debi Dayal v. Ghasita, AIR 1929 All 667, Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/920390/, last seen on 14/04/2023

- Difference between condition precedent and condition subsequent clauses in an investment agreement, ipleaders, available at https://blog.ipleaders.in/difference-between-condition-precedent-and-condition-subsequent-clauses-in-an-investment-agreement/, last seen on 15/04/2023

[1] Art. 246, the Constitution of India

[2] Schedule 7, the Constitution of India

[3] Raj Kapadia, Restrain on Transfer of Property, Legal Service India, available at https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-4151-restrain-on-transfer-of-property.html, last seen on 13/04/2023

[4] Dr. GP Tripathi, The Transfer of Property Act, 24 (19th ed., 2020)

[5] Dr. GP Tripathi, The Transfer of Property Act, 117 (19th ed., 2020)

[6] Dr. GP Tripathi, The Transfer of Property Act, 120 (19th ed., 2020)

[7] Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/853636/, last seen on 14/04/2023

[8] Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/469807/, last seen on 14/04/2023

[9] Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/920390/, last seen on 14/04/2023

0 Comments