This article is written by Chhavi of 6th Semester of New Law College, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed To Be University, Pune, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

The Sati Prevention Act of 1987 is a landmark piece of legislation in India’s fight against Sati, although it still faces challenges like shoddy implementation, vague definitions, social stigma, and a limited scope. However, shifting perspectives highlight how crucial it is to abolish this practice through community involvement, women’s empowerment, holistic approaches, and international collaboration. The three key objectives for the future are to support law enforcement, empower survivors, and encourage societal change through community involvement and education. Ongoing adaptation and collaborative effort are crucial to achieving a Sati-free future where women’s rights and dignity are completely respected.

As of 1829, it is banned in India, but there are still sporadic incidents. It is traditional to honor a woman for her perceived authority and value if she choose to die next to her husband. The historical context revolves around Sati, also known as Pavarti, who self-immolated as a result of her father disapproving of their marriage to the god Shiva. Rajasthan is a well-known Sati hotspot in India; Madhya Pradesh and Nepal have also been mentioned as Sati hotspots. The Indian Sati Regulation Act of 1829, presented by Lord William Bentinck and supported by Raja Rammohan Roy, was a significant piece of legislation. Later amendments distinguishing between culpable homicide and murder relaxed the criminal clause in 1860.

An important turning point in India’s continuous fight against Sati is the Sati Prevention Act of 1987, which combines social, legal, and cultural interventions. Even with advancements, obstacles still exist, calling for ongoing efforts to end this harmful custom and defend the rights and dignity of women.

KEYWORDS

Sati, Widow Burning, Sati Prevention Act, Rituals, Caste System, Social Stigma, Gender Inequality.

INTRODUCTION

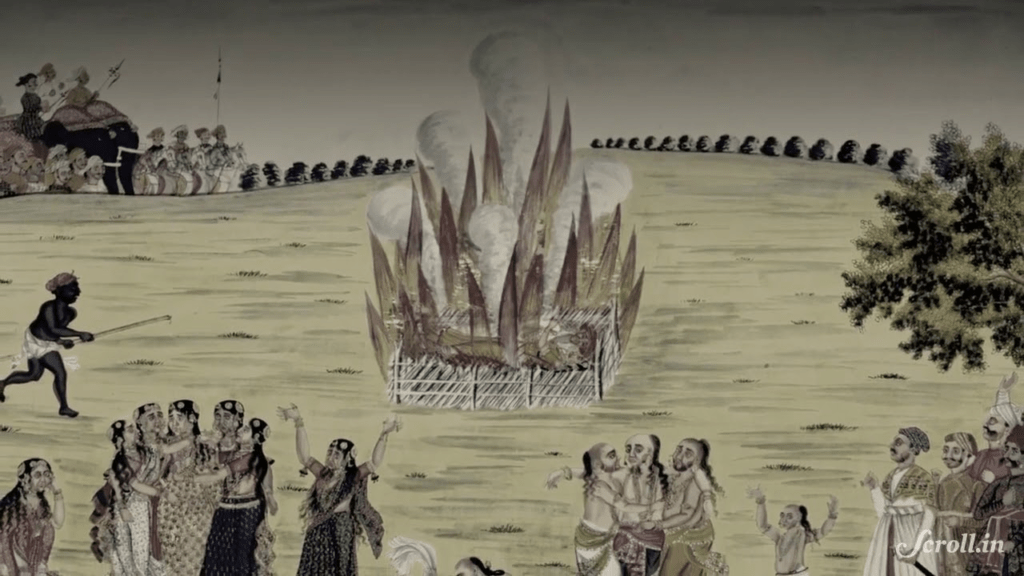

The word “SATI” is derived from the goddess Sati, who burned herself alive when her husband Lord Shiva was degraded by her father Prajapati Daksha. The expression originally indicated a “chaste woman” or a “good wife”. The old Indian ritual of burning widows on funeral pyres or burying them alive in their husbands’ graves became linked to it. Though scholars observe that it was more common among upper castes like as the Kshatriya, the second highest caste associated with the armed forces and governance, it is believed to have never been a widespread practice. The earliest known instances of sati occurred between 320 and 550 CE. As of late, sati has mostly been found in Rajasthan and has also been reported on the Ganpati Plain. Even though it has been illegal in India since 1829, there are still a few documented cases of sati there each year despite it never being extremely common. A woman who decides to die with her husband is regarded by others and her husband’s family for her great worth and power. Thus, a widow escapes disdain and gains fame for herself and her entire family as a result of her just death.

HISTORY

The deity Sati, thereafter known as Pavarti, was the god Shiva’s wife and the daughter of the illustrious sage Daksa. Because Daksa disapproved of Sati’s marriage to Shiva and did not extend an invitation to him for a special sacrificial ceremony, Sati passed away. She is associated with the other meaning of the term, sati, sometimes called suttee, because it is said in some stories that she joined the sacrificial fire. The ancient (and currently forbidden) tradition of a widow self-immolating on her husband’s funeral pyre is known as sati, or suttee. A chaste, virtuous lady or wife, or a woman who has a strong dedication to the dharma, can also be referred to as a sati or suttee.

The first people to actually practice ritual suicide were a small number of people in India. But as Hinduism became more well-known in India and other Asian and Indian nations, the practice gradually expanded. The Indian state of Rajasthan, located near modern-day Pakistan in the northwest, is the primary source of Sati’s fame. Furthermore, some instances were reported in the central state of Madhya Pradesh, which borders Rajasthan, and the northeastern Indian state of Nepal.

With Raja Rammohan Roy’s help, Lord William Bentinck introduced the “Indian Sati Regulation Act, 1829,” a law that prohibited Satí. It was referred to as: “A Regulation for declaring the practice of sati or burning or burying alive of the widows of Hindus, illegal and punishable by the criminal courts”. In 1860, the Indian Penal Code was drafted and added exception number 5, which says that if the victim, who is above the age of 18, dies or accepts the risk of dying, then culpable homicide is not considered a murder. As a result, the criminal clause against Sati is not as harsh.

SATI PREVENTION ACT, 1987

Roop Kanwar, then seventeen years old, gave herself up to flames on her husband Maal Singh Shekhawat’s funeral pyre on September 4, 1987, in the Deorala village in Sikar district, Rajasthan. In October 1996, an Indian court dismissed the father-in-law and brother-in-law of Roop Kanwar from the case due to insufficient evidence, despite the police accusation that they forced her to sit on the funeral pyre with her husband’s bones. On October 1, 1987, the Government of Rajasthan passed the Sati (Prevention) Act, an ordinance, as a result of widespread national and international outcry and a nationwide campaign. The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 was later passed by the Indian Parliament in 1988 as a means of defending widows.

Salient features of the Act:

- All states in the country are included.

- After the Central Government published a notice in the Official Gazette, it went into effect.

- Under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, this Act shall be administered.

- Act is punishable in court under the Indian Penal Code.

- Sati’s endeavor to follow the protocol and spearhead the procession in favor of Sati

- The Act of Sati is honoured by planning ceremonies, fund-raising, temple construction, and pujas to honor the Sati.

Attempt to Commit Sati:

- The maximum punishment for it is a year in jail, a fine, or both.

- The Indian Penal Code’s definitions of words and phrases shall apply to this Act as well.

- A Special Court will hear cases of this type and will take into account all relevant facts, the conduct of the accused, the accused’s mental state, and the events that preceded the offense.

Abetment Of Sati:

- Anyone who directly or indirectly aids in the crime of sati, if it is determined that someone has committed sati, faces the death penalty, life in prison, and a fine.

- Anyone who directly or indirectly aids in an attempt to commit sati faces life in prison and a fine in the case that sati is attempted.

- Aiding and abetting includes the following actions as well:

- Any encouragement given to a widow or woman to be burned or buried alive next to her husband’s bones;

- Supporting a widow or woman in her belief that her late spouse would benefit spiritually from the performance of sati supporting a widow to perform sati;

- Entering any procession associated with the commission of the sati;

- Achieving an active participation role at the designated place for Sati;

- Preventing the widow or woman from setting herself on fire or being buried alive;

- Hampered or hindering the police’s capacity to fulfill their mandate, which includes intervening to prevent sati from being committed.

Glorification of Sati:

- A fine ranging from 5,000 to 30,000 rupees and a sentence of imprisonment ranging from one to seven years. any ritual being performed or a procession being abandoned in relation to the act of sati; or

- Any form of encouragement, justification, or dissemination of the sati practice; as

- Putting on a celebration for the individual who must commit sati; or

- establishing a trust, raising money, building a temple or other structure, conducting worship there, or performing any rite there with the intention of honouring or keeping alive the memory of someone who has committed sati.

Procedure and Powers of Special Courts:

- Special Courts would be the venue for all Sati trials and processes.

- When a complaint is received, Special Courts have the authority to take action.

- The Chief Justice of the High Court concurs with the appointment of a judge by the State government to preside over the proceedings.

- As announced in the Official Gazette, they are required to exercise in that region.

- Furthermore, a Special Public Prosecutor is appointed by the State Government.

- Within 30 days from the date of the Special Court’s verdict or sentence, an appeal against an order issued by the court may be brought before the High Court.

Role of Special Courts:

- When trying any offence under this Act, a Special Court may additionally try any other offense to which the accused may be connected. The Special Court may find the accused guilty of any further offenses and administer any penalties allowed by this Act or other laws.

- Every day, the Special Court will hold witness depositions, trials, and inquiries. The Court will record the reason for the delay if it is decided that an adjournment is required.

- The Special Court shall have all the powers of a Court of Session to try any offence subject to the other provisions of this Act.

- Should a Special Court trial be held for an individual accused of transferring property in Sati’s name, Section 8 forfeiture would occur.

THE COMMISSION OF SATI (PREVENTION) RULES OF 1988

The rules pertaining to this act permitted the collector or the district magistrate to choose someone to assume the responsibilities linked to preventing sati, which are currently assigned to other officers. Other officers have to obey the collector’s or district magistrate’s directives. The relevant locality has the option to make the prohibitory orders in a typical fashion; these orders are essentially exhibits.

Before the structure of their temple collapses, the owners of temples and historic structures that they make an effort to preserve are entitled to a ninety-day notice period. An inventory of the property and details about its storage location will be prepared after such items are removed.

CHALLENGES AND CRITICS

- Gaps in Implementation: It’s still challenging to enforce the rule, especially in rural areas where patriarchal beliefs are deeply ingrained. Witness intimidation, police disinterest, and societal pressures can all hinder an effective investigation and prosecution.

- Identifying the Intent: Depending on how traditions and rituals are understood, it can be difficult to prove “abetment” or “glorification”. Decisions that are contested and accusations of cultural insensitivity may follow from this.

- Social Stigma: Survivors are likely to be rejected by their community and face social stigma and isolation, even if they were coerced or duped into trying Sati. Rehabilitation and reintegration require greater social awareness and support.

- Political Pressure: The Act’s effectiveness has occasionally been hindered by powerful politicians who have opposed its strict implementation under the sway of conservative organizations.

- Limited Scope: The Act primarily deals with court cases. To address the underlying social and economic causes of Sati, such as continuing gender inequality and poverty, more extensive societal changes and educational initiatives are required.

CONCLUSION

It is unfortunate that the present Indian administration gave up on trying to pass harsh sati legislation due to pressure from her own cabinet members. In any other civilized society, killing widows would be deemed murder; nevertheless, in India, this is a habit. It is shocking that when it comes to basic and straightforward human rights concerns like sati and dowry, the country is unable to overcome political and theological barriers.

An contentious and tragic part of Indian culture has been the mythological and historical tradition of Sati. Cases kept coming up even after the Indian Sati Regulation Act outlawed it in 1829; as a result, the Sati Prevention Act was passed in 1987. This law deals with aiding and abetting the practice of Sati as well as making efforts to commit the activity illegal. In order to ensure justice to handle Sati cases as quickly as possible, the Special Courts created by the Act are essential. Even though this destructive ritual has been significantly curbed, government enforcement and constant watchfulness are still necessary to erase Sati’s remains from society and protect women’s rights and dignity. To tackle this behaviour, the Sati Prevention Act, 1987 includes extensive social, legal, and cultural measures. Applying to all states, using the Indian Penal Code for punishment, and utilizing the Code of Criminal Procedure for enforcement are some of the most noteworthy features of the Act. Due to the Special Courts established by the Act, trials and procedures will go more quickly. A big step has been taken in the ongoing effort to eradicate Sati from Indian society with the passage of the Act, which upholds the rights and dignity of women and concentrates on prevention, prosecution, and widow empowerment.

The Sati Prevention Act of 1987, which combines social, legal, and cultural measures, is a significant turning point in India’s ongoing fight against Sati. The Act and the creation of Special Courts are evidence of the country’s determination to eradicate the last vestiges of Sati and protect women’s rights and dignity.

REFERENCES

- https://wcd.nic.in/commission-sati-prevention-act-1987-3-1988-excluding-administration-criminal-justice-regard-offences

- https://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-14112-a-critical-analysis-on-the-commission-of-sati-prevention-rules-of-1988.html#:~:text=The%20Commission%20Of%20Prevention%20Act,collector%20or%20the%20district%20magistrate.

- http://www.jis.journal.in/critical-analysis-of-sati-by-reshma-katragadda

- http://www.indiacode.nic.in

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is of a personal nature.

0 Comments