This article is written by Vaibhavi Shree of MIT World Peace University an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

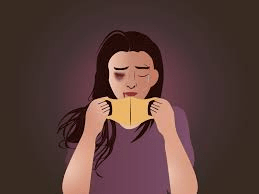

This article examines the legal and constitutional aspects of domestic violence in India with reference to the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA). It examines how the Act expands the definition of domestic violence to incorporate sexual, emotional, verbal, and economic abuse rather than only physical. It analyses the proximity of the law to constitutional guarantees of equality, dignity and liberty, particularly under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The conversation navigates its way through significant Supreme Court decisions that have broadened and defined the law on domestic as well as its interpretation in the context of non-traditional relationships such as live-in. It also discusses the institutional and cultural barriers to effective enforcement of the Act, including underfunding, lack of awareness, and significant differences among the courts on how they have interpreted the Act. Taking a critical view of the statute, the article suggests ways that the law can be reformed so that it fulfills its constitutional promise.

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence is rampant in India, and it happens all across, in every class, caste and religion. This kind of violence has historically been considered a private issue, and kept out of the realm of the law for extensive periods. The Indian Constitution, on the other hand, envisions a society based on principles of justice, equality, and the dignity of the individual. Amidst increasing acknowledgment of domestic violence as a public wrong and human rights violation, the Indian legal system finally reacted with the enactment of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005[1]. For the first time, anyone other than the offender had recourse to civil recovering action under that Act. It broadens the legal understanding of domestic violence to include a spectrum of harm when in fact, ranging from physical and sexual abuse to verbal insults and financial deprivation.

This Act is based mainly on the Constitution’s Articles 14[2], 15[3], and 21[4]. Article 14 represents the principle of equality before the law; Article 15(3) allows the State to make special laws for women and children, in recognition of their historical and structural disadvantage, and Article 21 embodies the right to life and personal liberty, which the courts have determined includes the right to dignity, safety and a home. These ideals are the moral and legal underpinning of the PWDVA.[5]

Courts have been critical in determining exactly how the law applies, particularly in nontraditional domestic arrangements, like live-in relationships. Cases like Indra Sarma v. V.K.V. Sarma[6] and D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal[7] have contributed in defining the legal contours of domestic relationship and the persons eligible for protection. Meanwhile, the judgements have thrown up several constitutional and gender justice issues, in particular, the reach and interpretation of the Act.

This article examines the definition of domestic violence; the types of relationships to which the Act applies and the constitutional values canvassed by the Act. It does so by critically assessing obstacles to the implementation, legal protection gaps and necessary reforms. In its examination, this paper seeks to demonstrate how the law of domestic violence in India is simultaneously an instrument of gender justice and an index of the changing dynamics between constitutional aspirations and everyday experiences.

UNDERSTANDING OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN INDIAN SOCIETY

The term “domestic violence” means abuse against an individual occurring in a domestic setting. Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, Section 3 defines it in a broad sense to cover physical, sexual, verbal, emotional and economic abuse. It also encompasses the threat to cause such acts. This is a historic definition as Indian law had until then acknowledged cruelty only under section 498A of Indian Penal Code[8] that was available to married women and was constrained to physical violence.

Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act departs from it, and provides a gender-sensitive and victim-focused definition. The principle that right to life includes the right to live with dignity, was however expanded by the Supreme Court in Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi[9]. This judgement set the tone of laws like the PWDVA which are designed to protect the dignity and independence of a woman in her private life. The Act is also committed to the protection of the rights and welfare of victims not only on the punishment of offenders.[10]

TYPES OF ABUSE RECOGNIZED UNDER THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT

Domestic violence under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act refers to abuse in the form of:

Physical Violence: This is any kind of physical threat, assault, or aggression. This is consistent with the wider interpretation of body integrity under Article 21, laid down in C. Masilamani Mudaliar v. Idol of Sri Swaminathaswami Thirukoil[11].

Sexual abuse: It is when the woman is subjected to sex against her will without giving consent, even in a marriage, it is widely recognized that marital rape is abuse under the provisions of this act. The acclamation is gradual since Supreme Court has so far been quite reluctant to accept marital rape.

Verbal and Emotional Abuse: This involves insults, and belittling, especially in relation to infertility and not having a male child. Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan[12] set the tone for recognizing non-physical forms of abuse as infringing dignity.

Economic Abuse: Frequent withholding of money, keeping the victim from accessing her money or property or denying her joint credit or access to family income. The PWDVA equally acknowledges economic rights and is consistent with the Supreme Court’s stand in Danial Latifi v. Union of India[13] that economic maintenance is a fundamental right.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND CONSTITUTIONAL GUARANTEES

The Indian Constitution does not explicitly mention domestic violence; however, its provisions underpin the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. Equality before law and equal protection of laws. The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India. Article 15(1) prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex and Article 15(3) authorizes the State to make special provisions for women. This space to legislate is what led the lawmakers to draft a gender-oriented regulation.

The right to live has been judicially understood to include rights to live with dignity, shelter and against violence, as part of Article 21. In Chameli Singh v. State of U.P.[14] it was observed that right to shelter has been held to be a Fundamental right under Article 21.

That dignity is at the core of the right to life was also reiterated in Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation v. Nawab Khan Gulab Khan[15]. These judicial constructions go far in legitimizing civil protections provided by the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.[16]

LIVE-IN RELATIONSHIPS AND THE AMBIT OF PROTECTION

PWDVA is remarkable in that it covers the live-in relations also. But not all live-in relationships are automatically protected. In D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal, the Supreme Court decided that a “relationship in the nature of marriage” must bear resemblance to marriage that is people living together, financial responsibility, and social acceptance. In Indra Sarma v. V. K. V. Sarma, the Supreme Court held that casual or adultery-oriented relationships are not included.

In Revanasiddappa v. Mallikarjun and Badri Prasad v. Director of Consolidation[17], the Supreme Court devised parameters to ascertain whether a live-in relationship is of the ‘nature of marriage.’ These include duration of cohabitation, public presentation as a couple, the nature of their financial and domestic policies, whether they intend to live together, and whether or not they have children. Relationships that are casual, short-lived, or adulterous do not qualify. So, the legal protection is confined to arrangements that mimic a permanent, committed marriage.

This acknowledgement is hugely significant, because many women are dealing with non-married relationships and not see also subjected to the same forms of abuse as married women. This was a fundamental step toward inclusivity and gender justice, bringing the law closer to life.[18]

LEGAL REMEDIES AND RIGHTS UNDER THE PROTECTION OF WOMEN FROM DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 is congruent with constitutional objectives in safeguarding several rights of women:

Right to Residence: Section 17 also ensures right to live in the shared household and no custom, practice or contract can take away that right from a woman. This view was affirmed in S.R. Batra v. Taruna Batra though the judgment drew flak for its strict reading of the law.

Protection Orders: A protection order is about stopping future violence and it’s a preventive measure.

Monetary Compensation: In Section 20, women can claim costs arising out of the abuse. The alimony is designed to keep a wife in the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed.

Custody and Compensation: Order may be passed by courts for interim custody of children and award of compensation for mental shock and pain to meet the constitutional mandate of access to justice under Article 39A.

The law further makes it compulsory to provide ‘Protection Officers’ and service providers to help the woman access the legal process, again, a law that focuses on supporting, rather than merely just fighting.

OBSTACLES TO EFFECTIVE ENFORCEMENT OF THE LAW

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 is not free from challenges in its implementation, albeit its progressive orientation. The Supreme Court read down the expression “adult male” from Section 2(q), [Hiralal P. Harsora v. Kusum Harsora], to permit women to be made respondents. Critics say this move minimized the law’s emphasis on women as the foremost victims.

The Union government stopped funding for the PWDVA implementation in 2019 which has had a great impact on its structure. Many of the Protection Officers are overstretched in a multi-tasking role and are ill- trained. Legal aid is hardly available to poor and marginalized women.

There is also a cultural suspicion of treating domestic violence as much of a public wrong. Women frequently fail to file complaints because of pressure from society, fear of retribution or dependence on the women for work. These obstacles frustrate the law’s intended use.

CONCLUSION

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 represents a significant watershed in the context of law addressing domestic violence in India. It departs from the typical private-public divide in legal thought in recognizing that violence in the intimate, domestic setting is no less serious than in public spaces. This departure is firmly anchored in constitutional values of equality, dignity and liberty protected by Articles 14, 15 and 21. By including emotional, sexual and economic abuse and not just physical, the law broadens the lens through which we conceive of violence and how we seek to prevent and alleviate it. The law has been illuminated and violated with judicial interpretations. If cases such as Indra Sarma and Velusamy have put to rest doubts about which persons are covered by the Act, Harsora has generated a debate on reading a gender-neutral language in a statute enacted for protecting women from domestic violence. However, these conversations offer insights to the changing nature of domestic violence jurisprudence in India.

Implementation, however, remains a persistent challenge. Lack of adequate funding, training of officials, stigma and lack of awareness diminish the law’s effectiveness. In order for the Act to realize its promise, there is a need for institutional commitment, budgetary support, and reforms of legal aid. Further, inclusion of male children under the protection and strengthening of community-based support systems will help law to remain abreast of ground truths.

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 is ultimately a constitutional guarantee in action, not just a legal remedy. It has the power to change the way Indian society views domestic abuse and the way the state safeguards the weakest members of society in their own homes.

REFRENCES

- The Indian Constitution, 1950

- The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/constitutional-perspective-domestic-violence-act-2005/

- https://nyaaya.org/legal-explainer/are-live-in-relationships-covered-under-domestic-violence-law/

- https://www.naaree.com/domestic-violence-helplines-india/

- https://ijissh.org/storage/Volume4/Issue2/IJISSH-040204.pdf

- https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec03333cb763facc6ce398ff83845f22/uploads/2024/09/2024091127.pdf

- https://www.legalserviceindia.com/articles/dmt.htm

[1] Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005

[2] Article 14 of Indian Constitution

[3] Article 15 of Indian Constitution

[4] Article 21 of Indian Constitution

[5] https://www.legalserviceindia.com/articles/dmt.htm

[6] Indra Sarma v. V.K.V. Sarma (2013) 15 SCC 755

[7] D. Velusamy v. D. Patchaiammal AIR 2011 SUPREME COURT 479

[8] Section 498A of Indian Penal Code 1860

[9] Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi, AIR 1981 SC 741

[10] Sri M.Chandrasekhara Reddy, DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT, 2005, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec03333cb763facc6ce398ff83845f22/uploads/2024/09/2024091127.pdf

[11] C. Masilamani Mudaliar v. Idol of Sri Swaminathaswami Swaminathaswami Thirukoil (1996) 8 SCC 525

[12] Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan is AIR 1997 SC 3011

[13] Danial Latifi v. Union of India AIR 2001 SUPREME COURT 3958

[14] Chameli Singh v. State of U.P. AIR 1996 SC 1051

[15] Ahmedabad Municipal Corpn. v. Nawab Khan Gulab Khan, AIR 1997 SC 152

[16] Mr. Dillip Kumar Behera, Protection of Women from Violence under Constitutional Provisions, International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities (IJISSH), https://ijissh.org/storage/Volume4/Issue2/IJISSH-040204.pdf

[17] Revanasiddappa v. Mallikarjun (2011) 11 SCC 1

[18]Nyaaya, Are Live In Relationships covered under Domestic Violence law?, https://nyaaya.org/legal-explainer/are-live-in-relationships-covered-under-domestic-violence-law/

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is personal.

0 Comments