This article is written by Palak Anand of BA LLB of 3rd Sem of JIMS EMTC , Greater Noida, an intern under Legal Vidhiya

ABSTRACT

This paper talks about the institution of Nikah (Marriage) within Islamic Law, exploring its different dimensions as a legal, spiritual and social construct. Nikah is not just a union through marriage but it’s a binding contract that holds profound religious, cultural and societal significance in Muslim communities. The research of the paper examines the foundational principles of Nikah as written or highlighted in the Quran and Hadith, emphasizing its role in establishing marital mutual rights, responsibilities, peace and harmony between the spouses. The paper discusses the procedures such as prerequisites for validity, the role of consent and the contractual elements like mahr (dower). Further this paper talks about the dynamics of Nikah in contemporary contexts, it addresses challenges posed by evolving social norms, gender roles, and globalisation. Key focussed areas of the paper include meaning of Nikah, adaptability of Nikah to modern legal systems, its balancing approach between traditional and contemporary rights and values, and its impact of cultural diversity on its practice. By exploring more about Nikah as a social contract, this paper seeks to know its relevance and adaptability within Islamic jurisprudence and its role in shaping family structures and ethical values in Muslim societies. This research paper aims to contribute to a better understanding of Nikah in the broader discourse on Islamic family law and modernity.

Keywords

Nikah, Islamic marriage, Shariah, Islamic law, family law, marital contract, mahr, consent in marriage, gender roles in Islam, modernity, Islamic jurisprudence.

INTRODUCTION

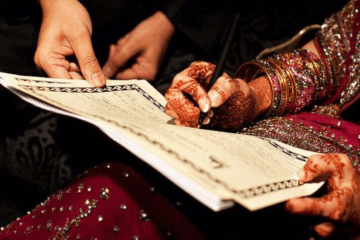

Nikah is the Arabic word which in the terms of law means marriage. Marriage is an institution signifying the permanent relationship based on mutual concept from both the spouses. The institution of Nikah is a cornerstone of Islamic social and legal frameworks, representing a union from mutual consent with contractual obligations and spiritual fulfilment. As highlighted in the Quran Nikah serves not only as a means to foster companionship and procreation but also as a safeguard against social immorality and disintegration of familial structures.[1] Unlike many traditional views of marriage, Islamic jurisprudence conceptualizes Nikah as a contract (aqd) rather than a sacrament, emphasizing its legalistic underpinnings and the mutual rights and responsibilities it entails.[2]

The procedural aspects of Nikah—including the role of Wali (guardian), mahr (dower), and witnesses—highlight its dual nature as both a legal and religious act.[3] Furthermore, Nikah transcends its contractual framework by enshrining ethical principles of equity, kindness, and mutual respect between spouses, as emphasized in Islamic teachings.[4] However, the adaptability of Nikah to contemporary socio-legal contexts raises pertinent questions regarding its implementation amidst evolving gender norms, cultural diversity, and globalization.[5]

According to Justice Mahmood, “Marriage among Mohammedan is not a sacrament, but purely a civil contract.”[6]

According to Tyabji : “Marriage brings about a relation based on and arising from a permanent contract for intercourse and procreation of children, between a man and a woman, who are referred to as ‘parties to one marriage’ and who after being married, becomes husband and wife.” [7]

NATURE OF MUSLIM MARRIAGE

Nikah, or Muslim marriage, is a unique institution that brings together legal, social, and spiritual dimensions. This is a contract marriage that distinguishes it from the sacraments of religious marriages practiced in other traditions. In the Islamic jurisprudence system, Nikah is a civil contract that emphasizes mutual consent, defined rights, and obligations, as opposed to purely spiritual or ceremonial acts.[8]

- Legal Nature: Under Islamic law, Nikah is essentially a contract with specific conditions that guarantee its validity, such as the presence of witnesses, the offer (ijab), and acceptance (qabul).[9] The marriage contract also includes a dower (mahr), which is a compulsory gift or payment by the groom to the bride, and this highlights the independent financial rights of the woman.[10] This contractual nature gives both parties the power to negotiate and set terms, including prenuptial agreements.

- Social Nature: From a social point of view, Nikah provides a basis for family life, establishing a legal framework for reproduction and meeting the emotional and physical needs of the individuals involved.[11] It also brings social harmony by formalizing relationships and providing ethical principles governing familial roles and responsibilities.

- Spiritual Nature: Beyond the legal and social dimensions, Nikah is a highly spiritual concept. It is considered ibadah because it is a Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and thus fulfils divine commandments. The Qur’an describes marriage as a means of achieving tranquillity , affection, and mercy between spouses.[12] This spiritual dimension elevates Nikah from a mere contract to a covenant imbued with ethical values and divine blessings.

- Contemporary Relevance: The nature of Nikah remains significant in modern contexts, especially in discussions regarding gender roles, human rights, and cultural integration. Firmly rooted in the Islamic law, Nikah has shown adaptability to changing cultural and legal environments and has thus remained an enduring and dynamic institution.

ESSENTIALS OR FORMAL REQUIREMENTS OF MARRIAGE

Under Muslim law, Nikah (marriage) is considered a contract that requires specific essentials for its validity. These essentials have been clarified and reinforced through judicial interpretations over time. One primary requirement is the presence of a clear offer (ijab) and acceptance (qabul), made in the same meeting without ambiguity. The case of Abdul Kadir v. Salima (1886)[13] established that marriage is a civil contract requiring mutual consent through clear offer and acceptance. Another essential is the competency of the parties, which includes factors like age, mental capacity, and religious compatibility. Courts, such as in Shamim Ara v. State of U.P. (2002)[14], have highlighted the importance of maturity and free consent, holding that forced marriages involving minors or individuals of unsound mind are invalid. Free consent is also an essential aspect of a valid Nikah , and duress or fraud can be such as to render the marriage void, as held in Khwaja Muhammad Khan v. Husaini Begum (1910)[15]. Under Sunni law, witnesses are a necessary requirement, but Shia law does not insist on witnesses and recommends them. In Zohara Khatoon v. Mohd. Ibrahim (1981)[16], the court reaffirmed that the absence of witnesses in Sunni marriages renders them invalid. Furthermore, mahr (dower) is a mandatory element in Islamic marriages, symbolizing the wife’s financial independence and security. The Supreme Court in Fuzlunbi v. K. Khader Vali (1980)[17] clarified that mahr is an essential obligation, ensuring the wife’s right to claim it during or after the marriage. Marriage under Muslim law also forbids alliances between persons related by consanguinity, affinity or fosterage. In A. Yusuf v. Sowramma (1971)[18], the court reiterated that such marriages are null and void. Lastly, the intention of permanence is a characteristic feature of Nikah. Where as temporary marriages like mut’ah are allowed in Shia law, Sunni law only allows the permanent unions as was established in Mohammad Shah v. Saida Begum (1934)[19].

Thus, these basics supported by judicial decrees emphasize the legal and moral significance of Nikah, thus it is valid and shows a perfect balance between traditional concepts and modern legal contexts.

RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF HUSBAND AND WIFE UNDER A VALID MUSLIM MARRIAGE

In a valid Nikah, or Muslim marriage, the rights and duties of the husband and wife are derived from Islamic principles and the terms of the marriage contract. These rights and obligations are mutual and emphasize equality, justice, and harmony within the marital relationship.

Rights of the Husband

- Right to Obedience: The husband is entitled to reasonable obedience from the wife, especially on matters related to the welfare of the family, but only if his demands are lawful and just.[20] In Itwari v. Asghari AIR 1960 All 684[21] – The court held that obedience must be fair and cannot infringe on the personal dignity or legal rights of the wife.

- Right to Consortium: The husband is entitled to cohabitation with his wife, developing companionship and intimacy in the marriage relationship.

- Right to Corrective Punishment: Orthodox interpretations allow the husband to correct the wife within limitations that are determined by teachings of Islam. However, this right is highly subject to scrutiny in modern jurisdictions in order to avoid abuses and exploitation.[22]

Responsibilities of the Husband

- Maintenance (Nafaqah): The husband is duty bound to provide for the wife’s financial needs, which include food, clothing, and shelter, irrespective of her wealth. In Shah Bano Case (1985 SCR (3) 844)[23] The court emphasized that the husband was duty-bound to pay maintenance to the wife even after divorce in some cases.

- Payment of Mahr: Mahr, or dower, is a compulsory payment to the wife, either at the time of marriage or deferred. It represents the wife’s economic security.[24] In Fuzlunbi v. K. Khader Vali AIR 1980 SC 1730[25]– The court held that mahr is not just a ritual but an essential marital duty.

- Just Treatment: The husband must treat his wife with tenderness and justice. In case of polygamy, he must treat them all on an equal footing with regard to financial and emotional affairs as the Qur’an ordains.[26]

Rights of the Wife

- Right to Maintenance: The wife is entitled to be maintained by her husband as long as the marriage subsists, regardless of her personal financial position.

- Right to Mahr: The wife has the right to claim the agreed mahr as part of the marriage contract.

- Right to Dignity and Respect: The wife has a right to dignity, kindness, and fair treatment. She must be protected from spousal violence or any form of psychological abuse. In Zohara Khatoon v. Mohd. Ibrahim AIR 1981 SC 1243[27]– The court was of the opinion that a wife is entitled to live with dignity and cruelty-free.

- Right to Children’s Custody: It is held that during their tender years, children’s custody might lie with the wife depending on the circumstances of the child.

Duties of the Wife

- Cohabitation: The wife owes a duty of cohabitation to the husband so as to maintain that companionship and intimacy envisaged by marriage.

- Care for the Household: Traditional Islamic teachings assign the wife responsibilities related to managing the household, though modern interpretations emphasize shared responsibilities.

- Obedience: The wife is expected to obey her husband in lawful matters, provided his demands align with Islamic principles and justice.

- Fidelity: The wife is obligated to maintain fidelity to her husband, refraining from extramarital relationships.

The rights and duties in a valid Muslim marriage given to the husband and wife actually reflect a balancing of obligations and entitlements, geared toward promoting concord and mutual respect between the two mates. Now, though there is more emphasis on complementarity, modern juristic thought and practice continue evolving to face problems in accordance with the established principles of justice and equality in matrimonial relationships.

THE ROLE OF MAHR

Mahr is a fundamental component of Nikah (Islamic marriage) in India, signifying the contractual nature of the union and securing the financial security of the wife. The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, governs mahr under the personal laws of Muslims in India, making it of both legal and spiritual significance. Indian courts have held that mahr is always enforceable, which forms an integral part of the rights of Muslim women. The obligation to pay mahr directly arises out of the principles of Islam, which have been codified into personal law in India. The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act 1937 mandates that issues relating to marriage, including mahr, are to be governed by Islamic law. Courts in India have recognized mahr as an integral part of marriage under the Muslim Personal Law. In Abdul Kadir v. Salima (1886 ILR 8 All 149),[28] the Allahabad High Court held that mahr is not a gift but an obligatory payment under Islamic law. This judgment provided a clear precedent and underlined the fact that mahr is a legal obligation of the husband.

There are two types of Mahr –

- Prompt (Mahr-e-Muajjal): Payable immediately upon marriage or on the wife’s demand.

- Deferred (Mahr-e-Muwajjal): Payable at a later date, often upon dissolution of marriage through divorce or the husband’s death.

The case of Maina Bibi v. Chaudhary Vakil Ahmad [29]clarified that mahr, whether prompt or deferred, is a debt owed by the husband and can be claimed by the wife or her heirs in case of non-payment. Mahr continues to play a crucial role in protecting the rights of Muslim women in India. It provides financial independence and serves as a mechanism to ensure accountability within marriage. Legal reforms and judicial precedents have strengthened the enforceability of mahr, but further efforts are needed to address cultural misconceptions and ensure its proper implementation. Mahr in India is a legal obligation and a social safeguard to the principles of justice and equity in Islamic marriage. Despite all these challenges, its effective enforcement through legal mechanisms ensures that it remains a vital tool for protecting women’s rights. Issues like non-payment and cultural distortions can further strengthen the institution of mahr to align it with its intended purpose in Islamic law.

RESTITUTION OF CONJUGAL RIGHT

Restitution of conjugal rights is when a spouse resorts to legal action against the other spouse with whom he/she has chosen to withdraw from the matrimonial relationship without any sensible cause. The concept was based on the rights and obligations arising from Nikah, wherein the couple cohabits and performs conjugal duties toward each other. It has been said in Moonshee Buzloor Ruheem v. Shumsoonissa Begum [30]that where a wife without lawful cause ceases to cohabit with her husband, the husband may sue the wife for restitution of conjugal rights. In Shahina Praveen v. M. Shakeel,[31] the wife filed a second appeal against the appellate order of the Additional District Judge, Delhi. The Additional District Judge set aside the order of the trial Judge. The case was dismissed in the court for the husband’s suit for restitution of conjugal rights. In jurisdictions like India, the restitution of conjugal rights are given under section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 which applies to the Muslim law under customary practice. The suit for the same can be filed by any of the spouse in the civil court seeking the restitution of the marital rights. The remedy of restitution of conjugal rights has been criticized in modern legal discourse for the potential infringement of individual autonomy and privacy. Courts in some jurisdictions have recognized the need to balance personal freedoms with the preservation of marital institutions. Despite its controversies, the concept continues to serve as a mechanism for resolving marital disputes and upholding the contractual obligations of Nikah. Various judicial opinions worldwide have recognized this sentiment while stating the importance to protect personal rights and personal liberties while holding sanctity over marital institutions.

For example, in Saroj Rani v. Sudarshan Kumar Chadha (1984)[32], the Indian Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the remedy under the Hindu Marriage Act but noted that its exercise should be made with the principle of fairness and justice in mind. But, of course, legal development such as the declaration of the right to privacy as a fundamental right in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017)[33] have cast doubts on whether restitution of conjugal rights as known can continue to be valid. Restitution of conjugal rights continues to play a significant role in Muslim law as a mechanism to settle marital disputes and enforce the contractual nature of Nikah. The reconciliation and mediation emphasized in Islamic jurisprudence is aligned with the Qur’anic principle of settling marital discord amicably. Modern approaches, however, seek more sensitivity to the power inequality that may be exercised over this remedy. Despite its controversies, the remedy remains an effective means of dealing with questions of matrimonial breakdown where reconciliation might be a possibility. Its application, however, must be subject to critical scrutiny so that violations of personal rights are avoided, and the principles of equity and justice are preserved.

The ethical implications of restitution of conjugal rights are particularly contentious. On one hand, it seeks to preserve the marital bond and fulfil the contractual nature of Nikah. On the other hand, it risks imposing undue pressure on a spouse, potentially exacerbating power imbalances within the marriage. In patriarchal contexts, the remedy has been criticized for disproportionately favouring husbands, as societal norms often prioritize the husband’s rights over the wife’s autonomy. This raises concerns about the misuse of the remedy to control or subjugate the wife. Critics argue that restitution of conjugal rights, particularly in its traditional form, is incompatible with contemporary values of individual autonomy, equality, and privacy. The remedy’s potential to coerce unwilling spouses into resuming marital cohabitation has been a focal point of legal reform discussions.

CHALLENGES IN TRADITIONAL NIKAH IN MODERN TIME

The institution of Nikah, or Islamic marriage, has been the core of social life for many Muslims. Therefore, mutual consent and rights and responsibilities in marriage remain an emphasis. As a contract and a spiritual bond, Nikah reflects the ideals of equity, fairness, and justice. However, traditional Nikah practice faces great challenges and criticisms in modern times, when societal norms are changing, gender roles are being redefined, and human rights and individual freedom are gaining greater importance.

1. Gender Inequality in Traditional Interpretations

One of the key criticisms of traditional Nikah is that it is perceived to favour masculine versus feminine gendered relations and, therefore is considered patriarchal. For example, unilateral talaq (divorce) pronounced by the husband without judicial review is often seen as unfair. This has led many to caution about talaq being misused, and women not having equal rights under other sections of Islamic law. While such reforms as the abolition of triple talaq in India through the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019 aim to address these concerns,[34] further measures are argued to be required to achieve gender parity.

2. Forced and Child Marriages

There are also forced and child marriages; these are absolutely against the spirit of Islam yet continue to find their way within some communities masked as tradition. Islam clearly and categorically mandates that a Nikah is not valid without both parties’ free consent, [35] and in the Qur’an, it further encourages marrying adults of appropriate maturity. However, because of societal customary practices, there are violations against human rights.

3. Polygamy in Modern Times

Polygamy, allowed by Islamic law with stringent provisos of equality among wives, has been a contentious issue in modern society. The critics think that the exercise of polygamy almost always results in inequalities toward wives and conflicts with the ideal of the monogamous partnership widely accepted today.

4. Socioeconomic and Legal Pressures

The rising cost of mahr (dower) and expensive wedding traditions impose much financial burden on families, deviating from simplicity as encouraged by the Islamic faith. This has been responsible for postponement of marriages, thus social problems like cohabitation outside Nikah marriage. Additionally, in non-majority Muslim countries, Nikah between Muslims usually suffers legal bottlenecks due to the failure of the system to equal civil marriage systems.

5. Individual autonomy vs. Family authority

The tension between individual autonomy and family authority in marriage decisions remains a challenge that is still pending. While Islam emphasizes the importance of free consent, family-imposed pressures or arranged marriages without genuine agreement persist in many cultures, undermining the autonomy of individuals, particularly women.

6. Mistaken understanding of Islamic Principles

A common misconception involves the misunderstanding of Islamic principles of Nikah due to cultural interference that often overrides religious teaching. Dowry demands, honour-based violence, and restricting women’s mobility are all incorrectly perceived as Islamic values when they actually have no relation to Islamic law. Traditional Nikah continues to face scrutiny in modern contexts as societal values evolve. While its foundational principles remain timeless, challenges such as gender inequality, forced marriages, and legal recognition highlight the need for reform and reinterpretation. Addressing these issues requires a return to the core values of justice, equity, and mutual respect emphasized in Islamic teachings while adapting to contemporary human rights standards. This will enable Nikah to remain an institution that is both relevant and fair, balancing spiritual and social needs.

CONCLUSION

The idea of the restitution of conjugal rights under Muslim law highlight more the contractual and spiritual aspects of The Nikah. Based on rights of each other, it shows how essential the concept of marital cohabitation is in Islamic family. In its intention to uphold and protect the institution of marriage through reconciliation and preventing wrongful withdrawal the remedy equally presents numerous legal and ethical concerns in the modern world. The arguments against restitution, including its capacity to violate individual liberty and privacy argue about the emergent forces present in the quest to assimilate Shari’ah law to the prevalent everywhere legal systems therefore the continual novel struggles. However, its application remains relevant to help provide a way to settle marital conflicts and affirm the contractually based foundation of Nikah. This remedy is best understood when there is an understanding of the principles of law as well as justice and equity that is primary to Islamic laws and yet the society’s concern for marital harmony. Since societies and legal systems change over time certain such concepts need to be studied anew and explicated to make them precisely congruent with core rights and ethical principles. The changing dynamics of modern society require the reassessment of such traditional remedies as restitution of conjugal rights. In the modern world, where individual liberties, private lives, and equality are highly touted, any legal mechanism that may have a potential to impose obligations felt coercive must be adjudged and made in tandem with modern principles of human rights.

The challenge is to ensure that the core values of justice, fairness, and mutual respect of Islamic law are preserved in dealing with the practical realities of the modern world. From a jurisprudential point of view, the remedy of restitution of conjugal rights under Muslim law has to evolve to protect vulnerable individuals, especially women, from abuse or exploitation. Scholars and jurists must navigate the delicate balance between preserving the sanctity of marriage and preventing the remedy’s application in ways that could perpetuate injustice or undermine personal dignity. This calls for a nuanced interpretation of Shari’ah that harmonizes traditional principles with the needs of a more egalitarian society. Further, the appropriateness of the remedy can be understood within the broader contours of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, intrinsic to the law of Islam. As mediation and arbitration are the Qur’anic recommendations for an amicable solution to marital discord, thus reducing the hazards of litigation or forced compliance, a turn towards them may guarantee the spirit of restitution—that of marital conciliation—while not undermining the liberties of the individuals concerned.

Moreover, the law of every country in the world, be it a country with Islamic jurisprudence or otherwise, should find ways to include universal standards of human rights into its interpretation of marital law. Then, the remedy of restitution of conjugal rights will become a framework of mutual respect and voluntary reconciliation and not a tool for any form of compulsion or inequality. Ultimately, the future of restitution of conjugal rights depends on its ability to remain relevant and at the same time maintain the principles of justice and ethical governance that form the backbone of Islamic law. This calls for a continuous dialogue between tradition and modernity, ensuring that this age-old remedy evolves to meet the demands of contemporary society without losing its foundational essence.

REFERENCES

- Muslim Women Protection Act, 2019

- Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937

- Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act, 1939

- The Muslim laws Bare Act

- Aqil Ahmad Mohammedan Lawbook

- Mohammad Hashim Kamali, Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence 260–65 (3d ed. 2003).

- Abdullahi A. An-Na’im, Islamic Family Law in a Changing World: A Global Resource Book 42–45 (2002).

- Sayyid Sabiq, Fiqh-us-Sunnah vol. 6, at 150–55 (1991).

- Ziba Mir-Hosseini, Marriage on Trial: A Study of Islamic Family Law 78–84 (2000).

- Abdul Kadir v. Salima, (1886)8 All. 149 at 154.

- Tyabji Muslim law, 4th edn. pp..44-45.

- Jogu Bibi 33. v. Mesal Shaikh, (1936)63 Cal.415. See also Rahima Khatoon v. Saburjanessa,

- Mohammedan law

- Abdul Ahad v. Shah Begum

- Asaf A.A. Fyzee, Outlines of Muhammadan Law 126–28 (5th ed. 2008).

[1] Qur’an 30:21 (“And among His signs is that He created for you mates that you may find tranquillity in them, and He placed between you affection and mercy.”).

[2] Mohammad Hashim Kamali, Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence 260–65 (3d ed. 2003).

[3] Abdullahi A. An-Na’im, Islamic Family Law in a Changing World: A Global Resource Book 42–45 (2002).

[4] Sayyid Sabiq, Fiqh-us-Sunnah vol. 6, at 150–55 (1991).

[5] Ziba Mir-Hosseini, Marriage on Trial: A Study of Islamic Family Law 78–84 (2000).

[6] Abdul Kadir v. Salima, (1886)8 All. 149 at 154.

[7] Tyabji Muslim law ,4th edn. pp..44-45.

[8] Asaf A.A. Fyzee, Outlines of Muhammadan Law 104 (5th ed. 2008).

[9] Qur’an 4:4 (“And give the women their dower as a gift graciously.”).

[10] Tahir Mahmood, Personal Law in Islamic Countries: History, Texts, and Comparative Analysis 56–59 (1987).

[11] Qur’an 30:21 (“And among His signs is that He created for you mates that you may find tranquillity in them, and He placed between you affection and mercy.”).

[12] Sayyid Sabiq, Fiqh-us-Sunnah vol. 6, at 152–55 (1991).

[13] Abdul Kadir v. Salima (1886)

[14] Shamim Ara v. State of U.P. (2002)

[15] Khwaja Muhammad Khan v. Husaini Begum (1910)

[16] Zohara Khatoon v. Mohd. Ibrahim (1981)

[17] Fuzlunbi v. K. Khader Vali (1980)

[18] A. Yusuf v. Sowramma (1971)

[19] Mohammad Shah v. Saida Begum (1934)

[20] Mulla, Principles of Mahomedan Law 270 (22d ed. 2017).

[21] AIR 1960 All 684

[22] Abdur Rahim, The Principles of Muhammadan Jurisprudence 212 (1911)

[23] (1985 SCR (3) 844)

[24] Qur’an 4:4 (“And give the women their dower as a gift graciously.”)

[25] AIR 1980 SC 1730

[26] Qur’an 4:3 emphasizes fairness and equity in the treatment of wives.

[27] AIR 1981 SC 1243

[28] Ibid (13)

[29] Maina Bibi v. Chaudhary Vakil Ahmad (1924 AIR 197 PC)

[30] Moonshee Buzloor Ruheem v. Shumsoonissa Begum(1867)

[31] Shahina Praveen v. M. Shakeel (1983)

[32] Saroj Rani v. Sudarshan Kumar Chadha (1984)

[33] Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017)

[34] Muslim Women Protection Act, 2019

[35] Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937

Disclaimer: The materials provided herein are intended solely for informational purposes. Accessing or using the site or the materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship. The information presented on this site is not to be construed as legal or professional advice, and it should not be relied upon for such purposes or used as a substitute for advice from a licensed attorney in your state. Additionally, the viewpoint presented by the author is personal.

0 Comments